Political leaders tend to fixate on the most tangible and visible aspects of the manufacturing process – the factory floor. But focus on the assembly line misses a much larger part of the value chain.

Design, supply chain management, aftercare and servicing are likely to add much more value than the assembling of parts in cars or washing machines. Even for complex and expensive machines, such as passenger jets, assembly is a low-value proposition compared with making the parts that go into them.

Politicians also tend to draw a sharp line between goods and services. For manufacturing companies themselves this line is increasingly blurred. Even the auto industry, the archetypal provider of blue collar manufacturing jobs, sees its future in the provision of “mobility services” rather than just cars.

Running fleets of leased cars, shared rides and autonomous vehicles are integral to their future business strategies. Similarly, in raw materials, suppliers of cement and steel, such as Arcelor Mittal and LafargeHolcim, position themselves as service providers, offering design and consulting services to manufacturing and construction companies.

Manufacturing jobs are on the decline

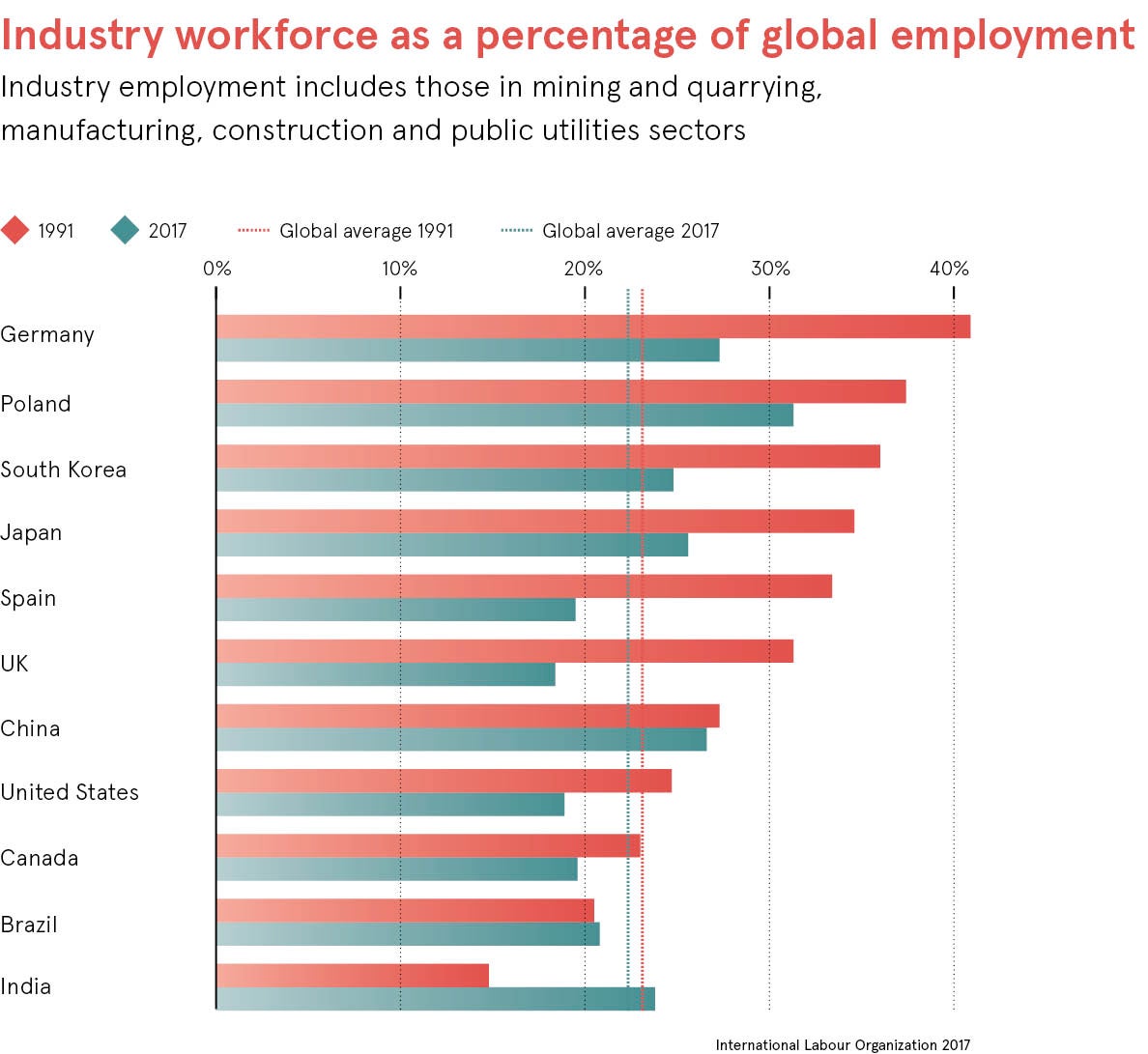

There is no denying that employment in manufacturing is falling. In the United States, it employs less than 10 per cent of the workforce, compared with 25 per cent in 1970. In the UK, 10 per cent of the workforce are employed in the sector compared with 33 per cent in the 1960s. Even in Germany, according to the World Bank, just 27 per cent of jobs are in manufacturing, down from 41 per cent in 1997.

But politicians who bewail the sector’s drop in share of GDP as a symptom of its overall decline are misled. Current GDP metrics fail to account for the practice of outsourcing and longer supply chains. Manufacturing companies increasingly contract other firms to manage marketing, catering, logistics, transport, IT services and accounting. Statistically, the replacement of a payrolled building manager with a contractor is indistinguishable from the disappearance of an assembly line job.

Advanced manufacturing will provide good jobs for skilled workers with diplomas or degrees

The fact remains that no industrial strategy will bring back good union-protected blue collar jobs. Low-skilled manufacturing jobs are mostly dead ends, with 62 per cent leading to no advancement in the US, according to research by JFF and Burning Glass Technologies, and new workers paid less than longer-term employees.

New manufacturing jobs created for skilled workers with qualifications

In the short term, advanced manufacturing will provide good jobs for skilled workers with diplomas or degrees. Such “new collar” workers are in high demand. On the factory floor, one worker with a masters degree will typically delegate to two with bachelor degrees and seven skilled workers.

“The US does a good job at churning out the first two [graduates]; what we have not done is a great job at the last [skilled workers],” says Stephen Catt, deputy director for workforce development at the Advanced Robotics for Manufacturing Institute.

The scale of these new collar jobs will be modest, offering nothing like the mass employment of years gone by. Even these will be supplanted within a generation, according to Adair Turner, chair of the Institute for New Economic Thinking and former head of the Financial Conduct Authority.

Governments that suppose otherwise are fighting a losing battle. “It is almost inevitable that by 2100 all the factories in the world will employ no more than a minute share of all workers, maybe less than 1 per cent, making any attempt to ensure a large share of ‘real manufacturing jobs’ an impossible objective,” says Mr Turner.

Politicians should be focussing on workforce inequality across sectors

Extreme inequality, occasioned by widespread automation, should be a major concern for politicians the world over, far more pressing than job losses in manufacturing alone.

Bill Fotsch and John Case, proponents of open-book management, suggest employee profit-sharing schemes paired with complete transparency of company accounts as one way to boost engagement, productivity and wages. Staff at every level would be encouraged to take initiatives and responsibility for the company’s overall success and their personal dividends.

This sounds more promising than the default policy prescription offered across the political spectrum, which is “to equip people with the skills to flourish in a world of continuous change”, says Mr Turner. We also cannot presume that individual successful companies will create jobs in other parts of the economy or through their domination of a given sector, or several sectors; Amazon being a case in point.

Creating decent blue collar jobs should be central to industrial strategy

Similarly, the idea that teaching every person to code will help them flourish in an IT-intensive world is also flawed. Thirty years after the computer age began, the total number of workers employed in the development and production of computer hardware, software and applications remains at only 4 per cent. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts just 135,000 new jobs will be created in software development between 2014 and 2024, far fewer than for personal care aides (458,000), registered nurses (439,000) and home health workers (348,000).

Jobs in the caring profession are a far cry from metal bashing and forklift truck operating, and are hardly guaranteed to appeal to the majority of lesser skilled men and women, not least because such jobs are undervalued both in terms of pay and status.

Governments mulling over their future industrial strategy would do well to also focus on how to create decent and dependable employment for the less skilled in other socially and economically productive sectors, such as trades, social care and craft.

Manufacturing jobs are on the decline

New manufacturing jobs created for skilled workers with qualifications

Politicians should be focussing on workforce inequality across sectors