Despite a widespread perception that employment is more precarious and workers, particularly of the millennial generation, are increasingly job-hopping, the statistics tell a different story.

For example, when US-based Pew Research compared what percentage of 18 to 35 year olds from different generations stayed with their employer for 13 months or more, it discovered that 63.4 per cent of millennials chose to do so in 2016 compared with 59.9 per cent of generation X in 2000.

Indeed, Stephan Bevan, director of employer research and consultancy at the UK’s Institute of Employment Studies, believes the core labour market has stayed “remarkably stable”, even if certain “bits around the margins” are less secure than they were.

According to his data, the average time that an individual spent in a job in 1994 was 7.9 years, while two decades later the figure had risen to 8.2 years, partly as a result of the ageing workforce.

Moreover, between 1996 and 2016, the number of people in permanent posts remained steady at 79 per cent of the working population, while those in temporary work fell from 6.4 to 5.1 per cent. Self-employment levels rose from 13.4 to 15.1 per cent and the number of gig economy workers now stands at 4 per cent, with no comparable figures available.

Current workers are more demanding, not less loyal

“There’s a persistent narrative that job tenure is now more precarious and fleeting for most of the workforce, but the data doesn’t bear that out,” Mr Bevan says. “It’s true that younger people with less experience are finding it more difficult to settle into jobs that match their skills, but for the great mass of people who are older, things have stayed quite stable.”

He points out that while a graduate may have found a position to match their qualifications after taking one or two jobs 20 years ago, today it is more likely to be their third or fourth.

Robert Ordever, managing director of workforce culture specialist O.C. Tanner Europe, agrees. While he too believes that younger generations have always job-hopped more than older colleagues, what has changed is “their expectations of what makes a great workplace, which is very different to a few years ago”, he says.

According to the O.C. Tanner Institute’s 2018 Global Culture Report, creating a positive employee experience is not simply about providing a job for life. Instead it involves ensuring that each individual feels a sense of purpose and is offered suitable opportunities to help them achieve success. It is equally important for workers to feel appreciated as this boosts their sense of wellbeing and confidence, and encourages them to adopt a leadership role.

“If you ask people why they’ve changed jobs, they won’t say it was for money or a promotion,” Mr Ordever says. “These days they have a deeper appreciation of what a positive workplace looks like and are no longer afraid to say what they want; so they’re not less loyal, they’re just more demanding.”

Object is to keep workers engaged, not merely to keep them

But while these kinds of attitudes may initially have been driven by the millennial generation, they have now permeated across the age range. This means staff members, irrespective of their generation, expect more from employers than previously.

At the same time, progressive human resources departments are starting to realise that simply retaining employees for the sake of it is a false economy.

“The objective in the past was mainly to get staff turnover numbers down to save on recruitment costs,” explains Mr Ordever. “But today it’s less about just keeping people and more about keeping people engaged, so they provide value while they’re with you and become brand advocates when they leave.”

Retention rates will become less of a focus and it will be more about working with the best talent

This means an increasingly key element of an HR professional’s role will be acting as agents of change to optimise the workplace culture.

“There’s a real shift starting to happen in HR, but the challenge is getting the rest of the senior team over the line,” says Mr Ordever. “So HR professionals are having to become experts in influencing and selling to encourage the rest of the business to come on the journey.”

Retention in the future means embracing more fluid workforce

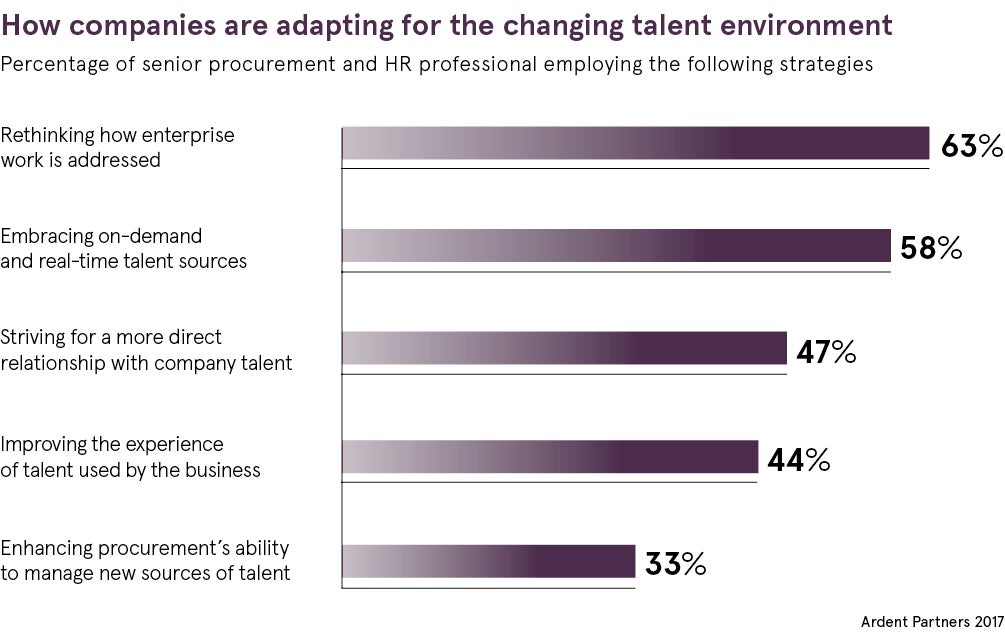

Meanwhile, a key way in which fresh talent will enter the business over the next three to five years is in the shape of growing numbers of freelancers and contractors, according to Fiona McKee, head of human resources at HR and payroll software supplier SD Worx UK & Ireland.

Although they may not yet be employed in great numbers, these gig workers will over time assume various roles right across businesses to enable them to respond quickly and in an agile way to market needs, she believes.

In other words, the secret to success will be in striking a balance between introducing fresh talent to bring in new ideas, and ensuring the company culture enables people to grow and develop by providing them with the right opportunities to do so.

While having a more fluid workforce will undoubtedly bring cultural challenges, it will also require a “broadening out of the definition of retention”, Ms McKee points out.

“Employers will still be keen to retain key people, but it will also be about looking at the wider business and ensuring you’ve got the right blend of skills, know-how and innovation to help you grow,” she concludes. “So we’ll see a more relaxed attitude towards retention; retention rates will become less of a focus and it will be more about working with the best talent.”