Fertility rates in sub-Saharan Africa are twice as high as the global average, but that doesn’t mean women in the region find it any easier to get pregnant. Combined with poor access to assisted reproductive procedures, scores of women have to cope with the devastating social and emotional consequences that come with not being able to bear children in many countries. For places that experience both high rates of both fertility and infertility – a phenomenon known as “barrenness amid plenty” – fertility technology or femtech would be an obvious starting point, but the reality is a lot more complicated.

The roles of women in society as childbearers and mothers puts a high price on being able to conceive

Ethical issues surrounding fertility in region with high birth rate

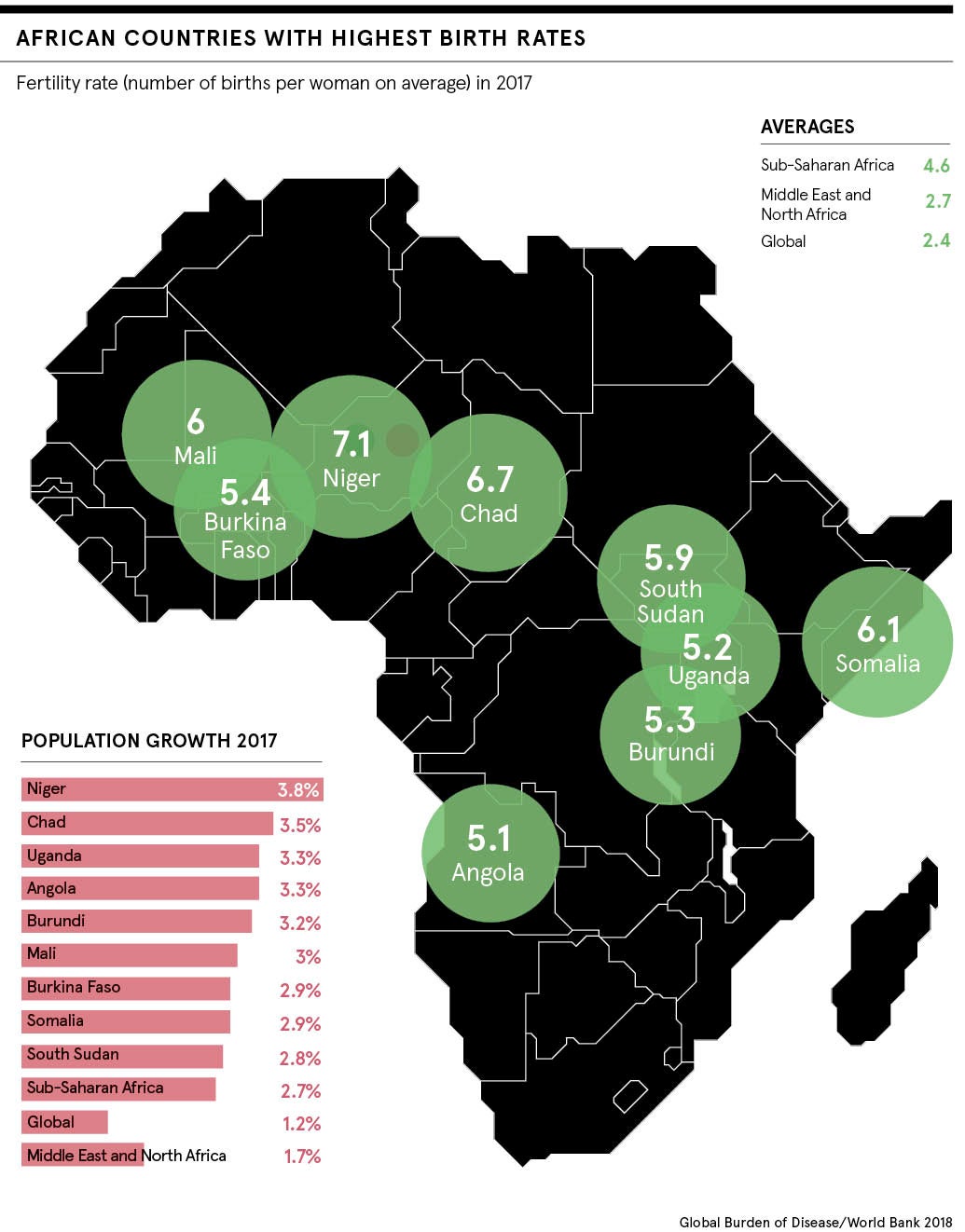

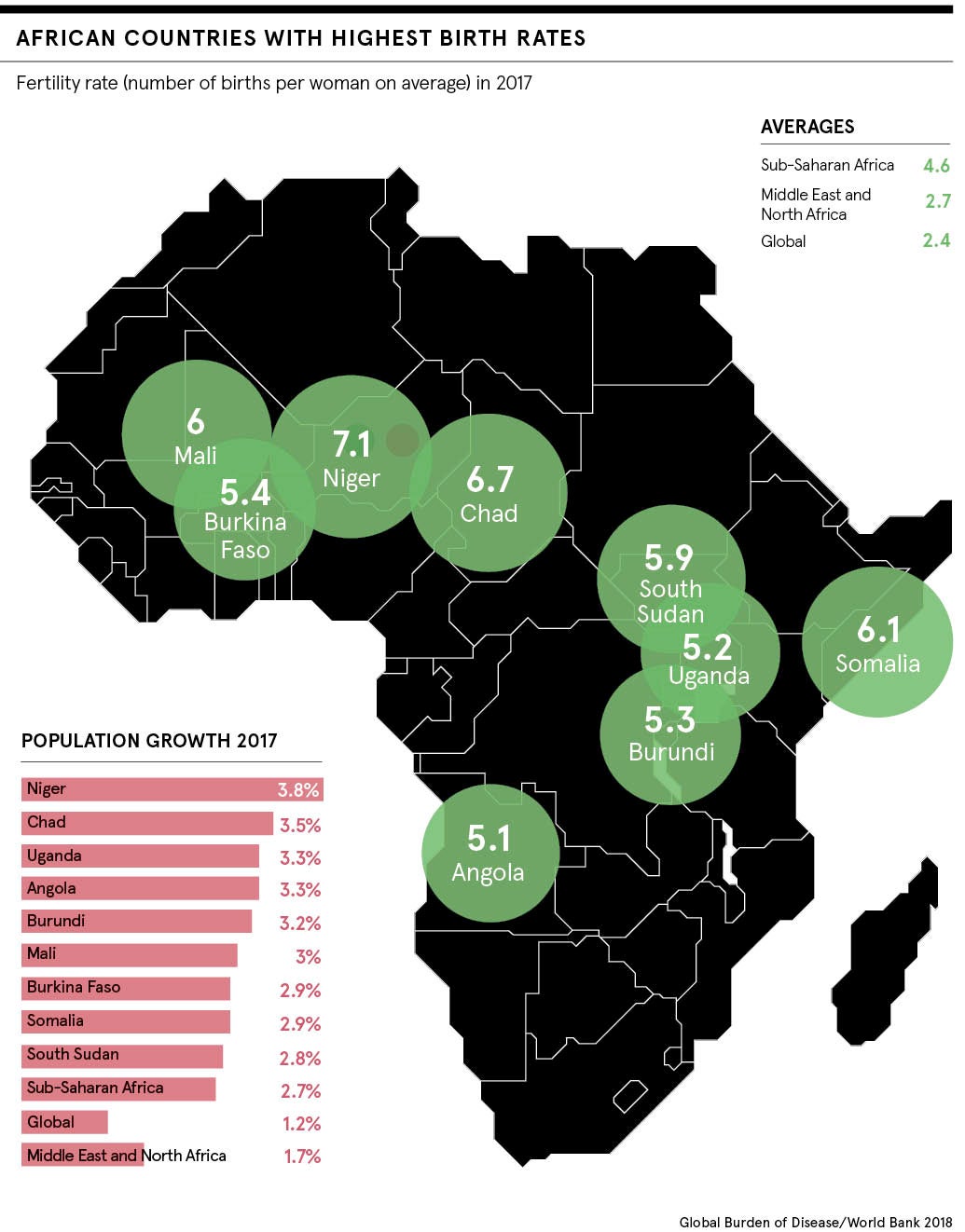

The average number of live births per woman across the world stands at 2.4, according to the latest statistics from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, down from 4.7 in 1950. In sub-Saharan Africa, although the average fertility rate has fallen dramatically over the past seven decades it still stands at 4.6 and is viewed by many as unsustainably high. According to the United Nations, Africa’s population will double by 2050 at current trends and will almost double again between 2050 and 2100.

Tackling issues to do with infertility may, to some, sound counterproductive in economies where many are calling for more rigorous population control. But it is attitudes like these that are inhibiting femtech development and which raise ethical questions around universal rights to healthcare.

Cultural issues play a major factor in the stunted growth of femtech in Africa. While male infertility accounts for half of all conception issues between heterosexual couples worldwide, the social ‘burden’ in many African regions often falls disproportionately on women. Viewed by some as a curse, the stigmatisation of infertility can be extreme and result in social anguish and ostracisation from families and communities.

“For women in developing nations, their roles in society are as childbearers and mothers, which puts a high price on being able to conceive,” says Thérèse Mannheimer, chief executive and founder of Grace Health, a Stockholm-based femtech company focused on emerging markets.

“This is of course equally difficult in any country, but the fall is higher when your value as a woman is a stake. Add the lack in education with women’s place in society and relationships, and you have a recipe for failure.”

Discussions around fertility in Africa, still turned into ones around overpopulation

With infertility viewed not as a widespread problem but more of an individual issue, nationwide preventative measures or fertility treatments have been neglected by public health authorities, and procedures such as in vitro fertilisation (IVF) remain unaffordable for the masses. This is all the more apparent in low-income economies that already face unprecedented population pressures.

The notion that femtech demand in Africa is not as high as other regions is of course misplaced, but an overall lack of focus on Africa as an investment target could equally be to blame. A study from KPMG in 2017 showed that of the $4.8 trillion raised for private equity funds worldwide between 2007 and 2016, just 0.6 per cent was allocated to Africa.

Rising populations is another key issue here. The Goalkeepers report in 2018 by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation warned that if current rates of population growth in Africa continue, the continent would have to quadruple its efforts just to maintain the current level of investment in health and education, which is too low already.

And yet, discussions around population remain an “elephant in the room”, according to Alex Ezeh, visiting fellow at the Center for Global Development. “Population issues are so difficult to talk about that the development community has been ignoring them for years,” Mr Ezeh wrote in the Goalkeepers report. He believes the primary goal of family-planning programmes is not to hit population targets: “On the contrary, it is to empower women so that they can exercise their fundamental right to choose the number of children they will have, when, and with whom.”

Opportunities for femtech in Africa are huge

Nevertheless, the economic prospects of femtech are bright. Unique mobile subscribers in sub-Saharan Africa totalled 444 million in 2017, according to the latest report from GSMA, with an additional 300 million expected to come online by 2025. This rapid surge in smartphone usage could be the very facilitator that’s needed to spread awareness and understanding of fertility issues across the continent.

One organisation hoping to do just that is Grace Health. The company, which provides period and fertility tracking via the Facebook Messenger platform, is targeting women in low-resource countries where there are restrictions in terms of data, hardware, networks or access to healthcare. Users are able to track and monitor symptoms, feelings and energy levels, and ask questions about their own health.

“Our first pilot market is Ghana since it is a proven proxy market for companies wanting to enter Africa, but we have already spread into 15 other countries just by recommendations, including Nigeria, South Africa and Somalia,” says Ms Mannheimer.

“Our mission is to make women’s health accessible to all women in an affordable, accessible, smart and relevant way. That means caring for early menarche, puberty, fertile years, motherhood, pediatrics and menopause. But at the moment we are focusing on period and fertility tracking to provide the best possible foundation for making an informed decision, whether you hope to get pregnant, want to avoid pregnancy or just want to learn about your body.”

The power of femtech to change mentalities

Elsewhere, Dubai-based Nabta Health was the first dedicated platform targeting women’s health across North Africa and the Middle East, helping customers through conception, pregnancy and the menopause. One of its solutions is Nabta Cycle, an artificial intelligence-driven period and ovulation tracker that allows customers to stay on top of their cycle, receive tailored insights about their fertility and book virtual consultations. It includes unique features such as a Hijri calendar mode and fasting schedule for Ramadan.

Sophie Smith, co-founder of the app, is hopeful that it will change mentalities: “Our hope is that North African women will use apps, wearable devices and see doctors. The whole point of Nabta’s hybrid healthcare model is that women will still see doctors, but they will be guided in these decisions by the technology they use and it will empower them to manage more aspects of their health themselves.”

In Rwanda and Kenya, ecommerce company Kasha enables women to buy health and personal care products such as sanitary pads and contraceptives, delivered confidentially to their home. The company, which already has more than 20,000 customers across both countries, also offers phone consultations on fertility, birth control and questions about sexual health, and has an optional offline text service to make services equally affordable for women who do not have a smartphone.

Making the mobile phone a tool for freedom

Hyacintha Ntuyeko, a Tanzanian entrepreneur who runs a menstrual hygiene campaign Hedhi Salama, believes femtech has the potential to give women options, but is aware of the challenges. “Femtech helps women make the best decision, but I am concerned these kind of services will only benefit middle-class women and leave behind women who live in rural areas who do not have power to go online due to number of barriers, including their ability to understand English or even how to read and write other languages.”

Grace Health’s Ms Mannheimer agrees that access to affordable digital tools plays a major factor in improving access to education, technology and fertility knowledge, but she remains optimistic. “1.9 billion women in low to middle income countries own their own phone, making the phone a tool for freedom. We believe deeply in not waiting for governments and organisations to come around, but to give the power to citizens and create change from the ground up and this is where innovation and entrepreneurship comes in.”

So far, femtech is carving a small place in the African market, but its potential to spread across the continent is enormous. As more apps and devices become available, there is hope that companies like Grace Health will begin to at least start more informed conversations about women’s health across Africa, and raise awareness that infertility is not just a developed-world issue, but one that thousands of women across low-income countries struggle with in silence every day.

Ethical issues surrounding fertility in region with high birth rate

Discussions around fertility in Africa, still turned into ones around overpopulation

Opportunities for femtech in Africa are huge