There has never been more information about fertility available, and yet it has never been harder to get clear, evidence-based answers to questions on the subject. Newly released data from a poll carried out for the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists found widespread confusion among women about their fertility. Although almost half of respondents had worried about their own fertility, four out of five had found available information contradictory, and more than three quarters were uncertain whether the information they were finding was impartial and unbiased. It is this confusion that led to calls for better fertility education for young people, and last month it was announced that it was set to be part of the curriculum in schools in England.

Organisations welcome the introduction of fertility education in schools

In the past, education about fertility and treatment has been covered in a rather patchy way in some biology and religious studies lessons at school, but the government has now published new draft guidance on Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education. The guidance is wide, covering many areas of health, relationships and wellbeing, but also makes it clear that by the end of secondary school young people should know “the facts about reproductive health, including fertility and the potential impact of lifestyle on fertility for men and women”.

This is something that many fertility specialists have been hoping for, particularly the campaigners in the Fertility Education Initiative, which was set up with the aim of improving knowledge of fertility and reproductive health. Founded by Professor Adam Balen, former chair of the British Fertility Society, it has a specific focus on the lack of understanding of age-related fertility issues.

The group welcomed the announcement about the inclusion of fertility education in RSE, as Professor Joyce Harper, the deputy chair, explains: “We are delighted that the importance of fertility education has been recognised. Men and women are delaying starting a family and we do not want couples to miss the boat. So it’s really important that key fertility issues are taught in schools, especially around female fertility decline and the limitations of what assisted reproductive technologies, such as IVF [in vitro fertilisation], can do.”

Fertility education early on can save couples disappointment

It is awareness of the limitations of what fertility treatment can achieve that many specialists feel is so essential. Fertility declines for both men and women as we get older, and people often assume that treatment will offer solutions if they wait to have children, but IVF cannot yet turn back the biological clock.

Author Lesley Pyne feels fertility education could have given her the information she needed when she and her husband started thinking about their future family. They did not start trying to conceive until Lesley was 35, unaware that her fertility was already starting to decline. They had six unsuccessful attempts at IVF, and Lesley has now written a book, Finding Joy Beyond Childlessness, to help others who are facing a future without children.

Ms Pyne says she is mindful of the fact that they might have the family they longed for if they had started trying earlier. “I really wish there had been more education about fertility and treatment at the time,” she explains. “I assumed IVF offered solutions and had no idea how rapidly my fertility was declining by the time we started trying. I feel offering more information about fertility to young women will help them to make informed choices for the future.”

Education moving from simply preventing teen pregnancy

Until now, education about fertility in schools has focused on how not to get pregnant, and strategies to reduce the teenage pregnancy rate in the UK have been successful. Knowing how to prevent pregnancy is only one side of the picture though, and most young people know very little about what may influence their future fertility.

A survey of 16-24 year olds for the Fertility Education Initiative found that 94 per cent said they would like to have children in the future, but many had gaps in their knowledge, with a quarter of boys thinking that women’s fertility only started to decline after the age of 40.

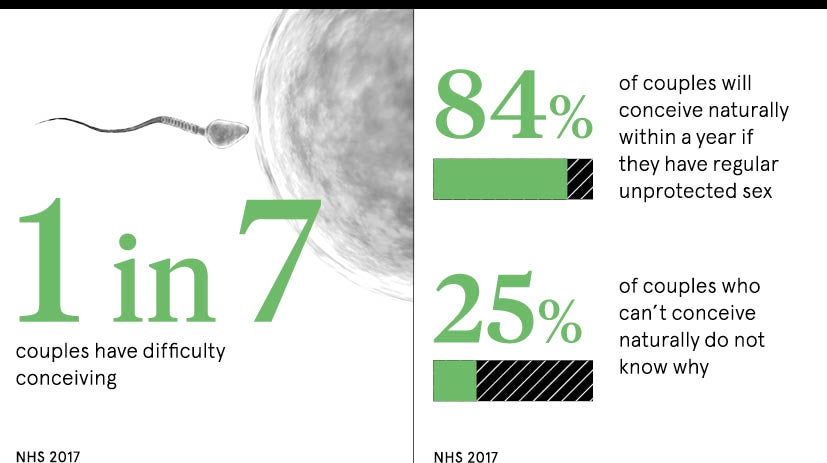

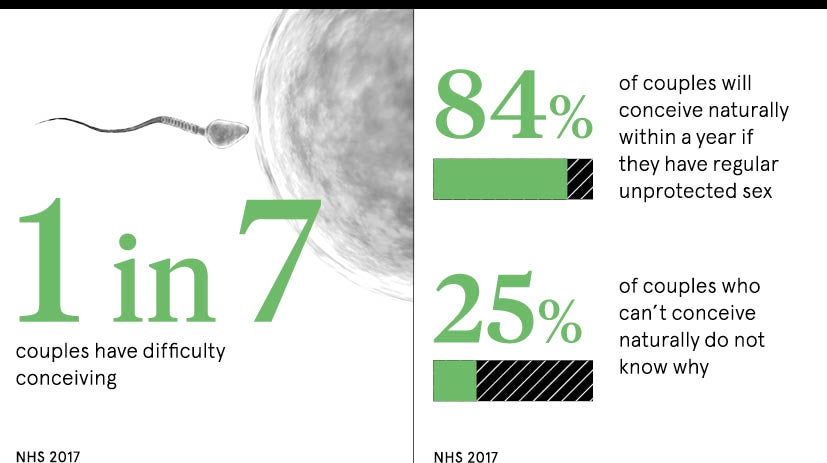

To most school pupils, future fertility seems light years away, yet we know that four or five pupils in every class of 30 will experience problems getting pregnant when they are older. It is essential that young people are given information in a way that is accessible, and one possible route is the use of the arts to educate.

Important fertility education is taught in the right way

Jessica Hepburn, founder of the fertility arts festival Fertility Fest, has worked with the Fertility Education Initiative on a project called Modern Families. Modern Families aims to use the power of the arts to increase fertility awareness among young people and to help them develop understanding of their own fertility, modern family-making and reproductive science.

Last year, the Modern Families team piloted workshops with young people at the National Theatre. Ms Hepburn says fertility education needs to be taught in the right way: “The task ahead is to furnish teachers with the most accurate and inspiring materials to ensure young people have all the information they need so they have the best chance of creating the families they want in the future, with or without children, with or without reproductive science.

“We believe the arts can play a really important part in making this information real to students and want to work with schools nationwide to ensure that fertility education is the very best it can be.”

A high-quality programme of relationships and sex education would not only help to prevent fertility problems in the future, but should also ensure that young people are aware of their fertility as part of a broader understanding of all aspects of their physical, emotional and reproductive health and wellbeing.

Organisations welcome the introduction of fertility education in schools

Fertility education early on can save couples disappointment