It’s the government’s big idea. All firms with an annual wage bill greater than £3 million must now pay 0.5 per cent of this in the form of a levy. The only way they can get it back, plus a 10 per cent sweetener, is to use the money for apprenticeships which, by the way, have been brought bang up to date by having trailblazer employers set the curriculums they want.

With skills shortages, employability and productivity all seemingly being tackled at once, government is hailing this as what employers have been crying out for. But is this the true story of the apprenticeship levy, five months in?

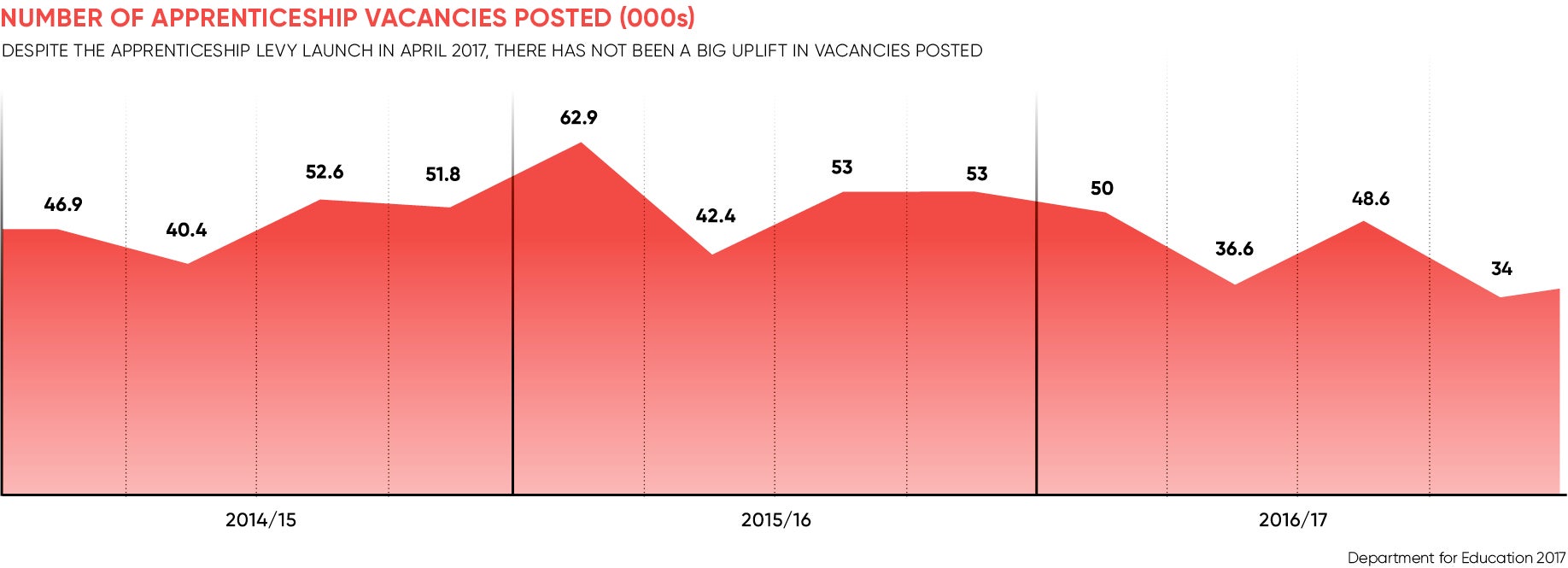

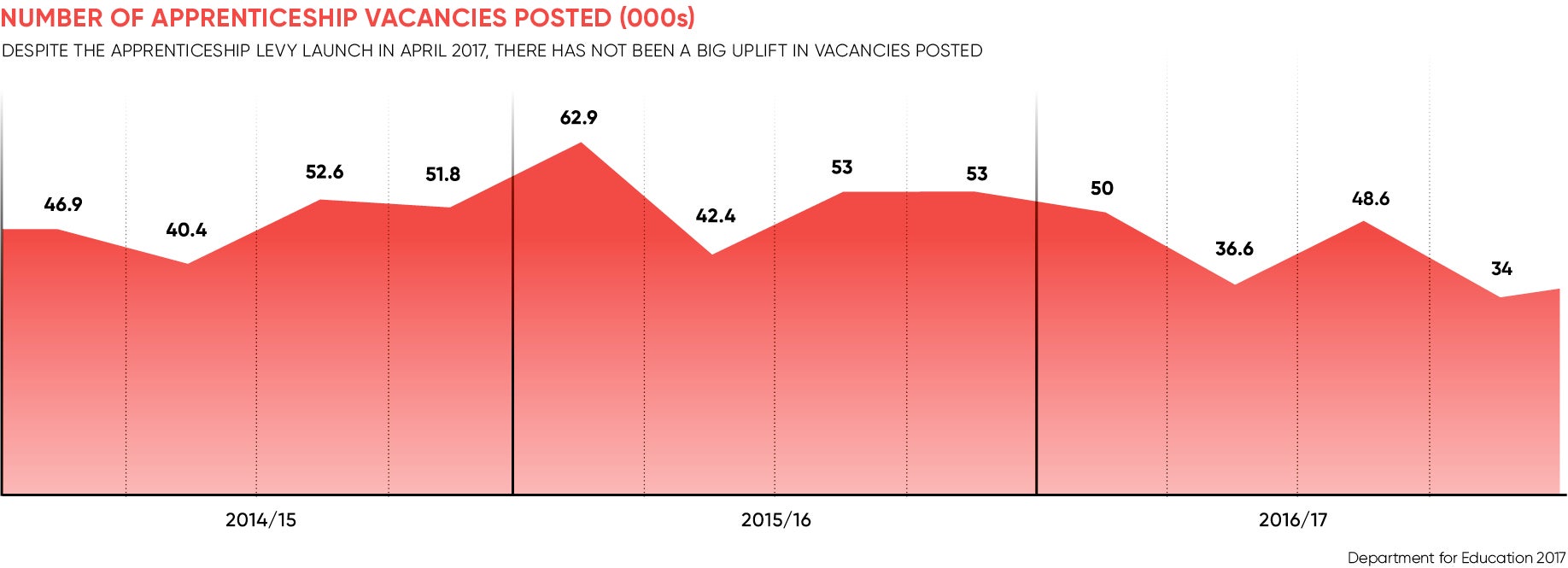

“The levy’s obviously here and firms are now making their payments, but what we’ve definitely seen is a fall in apprenticeship starts since May,” says Professor Helen Higson, deputy vice chancellor at Aston University, provider of higher-level apprenticeships. “The levy is definitely on finance directors’ plates now, but my sense is organisations are still grappling with how apprenticeships actually fit into their overall learning strategy.”

Critics of the levy argue that because an apprentice actually has to have a real job too, the limiting factor is that employers can’t actually find enough new roles fast enough.

Anouska Ramsay, talent director at Capgemini UK, says: “Overall we’re a big supporter of apprenticeships, because we need to create the skills of the future. But, due to our payroll, we’re paying more into the levy than we can actually spend back on ourselves. We can only use around a third of our levy; we’re in a similar boat to many employers, which is that it’s difficult to get our full money’s worth.”

According to research, the appeal of a learn-while-you-earn option is filtering down to students wary of being saddled with £40,000 of university debt. Half of 16 to 18 year olds now say they’ll consider an apprenticeship, according to the Association of Accounting Technicians.

But Professor Higson argues this isn’t yet filtering through to large enough numbers of employers, who are paying the levy now and need to use it or lose it within two years.

“Companies we talk to simply can’t get the students they need,” she says. “They’re paying the levy, but can’t simply get anyone to train.”

Coupled with employers’ frustrations that many new apprenticeship standards are not being approved quickly enough, a second fear is that in the panic to feel they’re getting value from their levy, firms will simply shoe-horn their existing training under an apprenticeship banner.

“This is a concern,” says Debbie Gardiner, chief executive at accredited apprentice training company Qube Learning. “This will mean employers are only delivering the same learning they already were. The only way they’ll see business improvement is with brand new learning.”

One firm that has been considering all these issues is laminate manufacturer Formica. “We’ll be paying more into our levy than we can claim back, but we’d rather do things properly, and plan our actual skills needs rather than do anything rash and spend it for the sake of it,” says Victoria Scott, its European talent and reward manager. “As such we’ve decided to take on apprentices in two phases, recruiting first into our manufacturing, engineering and also customer services sides of the business, but then we’ll see how this goes in terms of rolling out more apprenticeships next year.”

Considering EEF, the manufacturers’ organisation, finds 75 per cent of manufacturers are worried about value for money from their apprenticeship schemes, this is a sage approach. “We just have to accept they’ll be levy money we won’t use,” Ms Scott says. “That said, what we will be doing is creating new courses, in addition to existing learning, that will enable staff to take team leader and senior leader apprenticeships.”

Organisations are still grappling with how apprenticeships actually fit into their overall learning strategy

Just how well things pan out nationally depends on whether more organisations buy into the scheme equally enthusiastically. Many though still regard the levy as a tax, while some think it needs scrapping altogether.

“We think an alternative skills and productivity levy is needed,” says Clare McNeil, associate director for work and families at the Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR). “Our concern is most of the UK’s largest, that is levy-paying, companies are in the South East, so the levy will do little to redistribute investment in learning across the country. We don’t feel firms are being forced to think more holistically about their skills strategies, because they don’t see the bottom-line benefits.”

As the levy only affects 2 per cent of employers, the IPPR proposes starting it at firms with just 50 staff. Lowering the threshold would ensure learning reaches the majority of the small and medium-sized enterprise sector, which is home to most employment, says Ms McNeil.

But, it isn’t all doom and gloom. “Our apprenticeships are outstanding,” says Ms Ramsay, “and they play a valuable role in addressing social mobility. People are working with us, doing degree-level apprenticeships, who would have ordinarily bypassed the normal university route because of cost.”

Susan Bland, chair of the Hotel Employers Group and chief human resources officer at RedefineBDL Hotels, says: “The new standards are more straightforward, stipulate a 12-month minimum learning term and have a rigorous assessment process. I believe they should result in better trained, more confident, work-ready staff.”