When the Cambridge Analytica data scandal broke, it damaged the relationship between consumer data and social platforms. Facebook chief executive and co-founder Mark Zuckerberg made his most recent attempt to address such security fears earlier this month, posting a 3,200-word essay to his platform, entitled ‘A Privacy-Focused Vision for Social Networking.

There is the potential to provide a powerful understanding of demographics, but it’s harder to achieve in practice

Mr Zuckerberg ends the lengthy post with: “We should be working towards a world where people can speak privately and live freely knowing that their information will only be seen by who they want to see it.” Sadly, reputations are not repaired so easily. Drawing 10,000 comments, but only 3,600 shares, the post was “ratioed”, a Twitter coinage meaning more people answered back to a post, than liked it, or shared it, to express agreement.

“The timing of Mark Zuckerberg’s essay is interesting, almost a year on since the Cambridge Analytica scandal,” says Derek Roga, chief executive at encrypted communications firm Equiis Technologies. “But no matter what he says, essay or not, Facebook will never be known as a champion of data privacy. Consumers still remember how their personal data was commoditised and misused.”

Distrust of social media platforms growing among consumers

Facebook users gave up their data to the platform in a more innocent time, when signing up meant sharing personal content with friends and family. There was an expectation of privacy involved in the transaction. Compare this new Facebook user in 2005, or 2010, to someone setting up a LinkedIn account today. There are wildly differing levels of knowledge about data handling, as well as motives, at play in each scenario.

“For LinkedIn, the content of your profile has generally been something you want people to see; there are privacy settings available, but most of our members use LinkedIn to be found by colleagues, people they’ve met or potential employers,” says James Upsher, LinkedIn’s senior corporate communications manager, Europe, Middle East and Africa.

“One of the most popular features has been how it enables recruiters to find you and approach you with jobs that might be of interest. Our members are sharing information on the platform because they see direct value to themselves in doing so.”

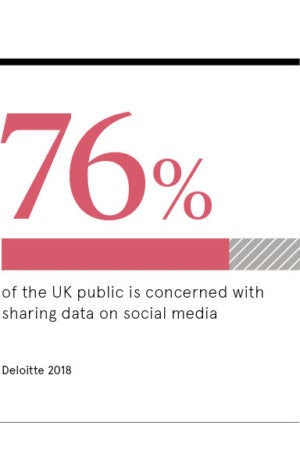

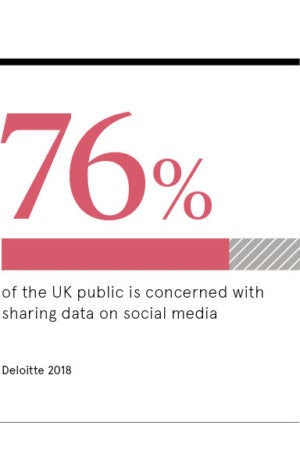

According to a survey of 4,000 people across the United States, conducted earlier this month by Jovi Umawing, senior content writer and researcher at cybersecurity firm Malwarebytes, just 12 per cent of respondents trust social media to protect their data.

The survey found that across the board there is a universal distrust of social media firms, among 95 per cent of respondents. Broken down by generation, baby boomers are the most distrustful of social media at 96 per cent, followed by gen Xers at 94 per cent. Gen Z and millennials showed distrust among 93 per cent and 92 per cent respectively, revealing a fundamental and comprehensive disconnect between social platforms and their consumers.

Social data is valuable because of its veracity and volume

Why do these networks want this reluctantly surrendered data? Jim Cridlin, global head of innovation at media agency Mindshare, says: “Social data is incredibly powerful as it tends to be extensive, longitudinal and accurate. While consumers tend to post their best self, their interactions, likes, follows and so on tend to reveal their true self. Moreover, there is pressure to keep social data shared with friends roughly truthful, as friends will call out that which is untrue.”

Why do these networks want this reluctantly surrendered data? Jim Cridlin, global head of innovation at media agency Mindshare, says: “Social data is incredibly powerful as it tends to be extensive, longitudinal and accurate. While consumers tend to post their best self, their interactions, likes, follows and so on tend to reveal their true self. Moreover, there is pressure to keep social data shared with friends roughly truthful, as friends will call out that which is untrue.”

Beyond the veracity of the data, there’s the sheer volume, which is a Holy Grail for marketers, according to Mark Brill, senior lecturer in future media at Birmingham City University. He says: “The potential power of data from social media is due not simply to its scale from billions of users, but also the frequency of their updates. That power to understand people has been frequently demonstrated. It would be possible to use this kind of data to identify the spread of infectious diseases, by marking the location and movement of users. There is the potential to provide a powerful understanding of demographics, but it’s harder to achieve in practice.”

Responsible data handling can reveal powerful insights

LinkedIn is using data for just that aim. The platform’s economic graph is a digital map of the global economy, which individuals, businesses and governments can use to navigate the decisions they have to make, says Mr Upsher.

He adds: “Through the information that our 610 million-plus members share on their public profiles, properly anonymised and aggregated, we’re able to help reveal trends. These insights are taken from all members, rather than a survey sample, and they are visible in real time. Insights from the economic graph, we hope, will remove personal and organisational barriers to economic opportunity.”

Recent projects powered by LinkedIn data include partnering with the World Economic Forum to look at gender gaps in artificial intelligence, working with the International Labour Organization, tracking how quickly women make it to director-level roles and an internal report on post-Brexit migration to the UK. The key takeaway from that last report is that fewer professionals from the rest of the world are moving to the UK.

User data could be the basis of more work that furthers understanding of the economy, society and our collective attempts at progress. Or it could be used to influence elections. Social networkers’ data is out of their control. Platforms and governments need to work together to keep data in the right hands, for the right reasons.

Distrust of social media platforms growing among consumers

Social data is valuable because of its veracity and volume