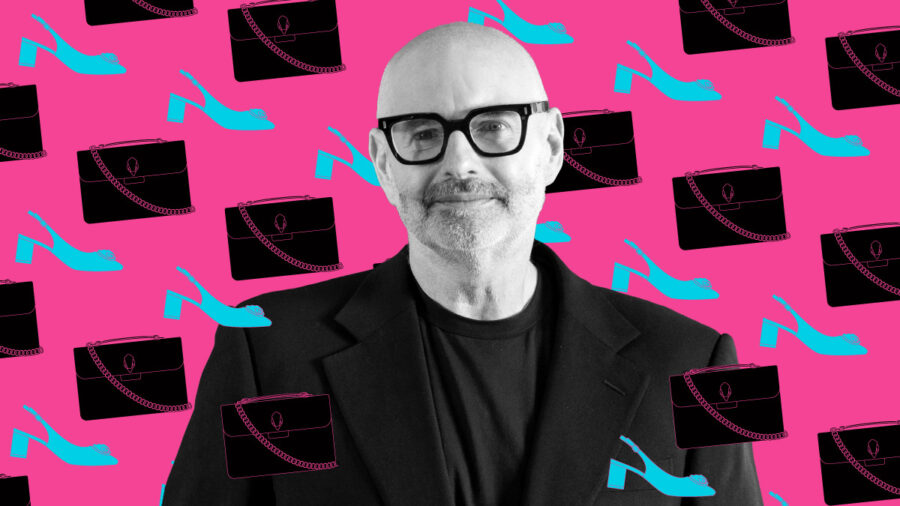

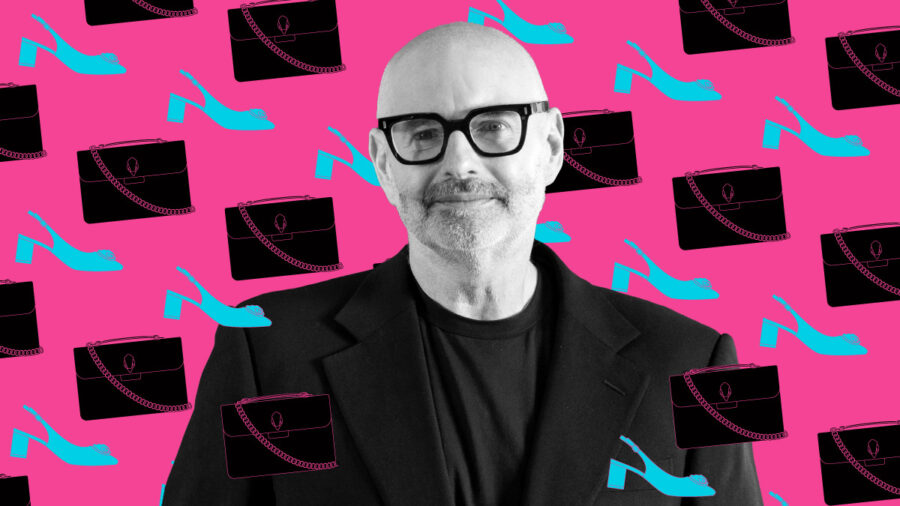

When I put it to Neil Clifford that many CEOs follow a similar journey to the top: university, a stint at McKinsey or one of the big four, then a corporate job, he laughs that he is “the yin to their yang.” The CEO of the British accessories brand, Kurt Geiger, could be viewed as the anti-blueprint chief executive. Struggling with dyslexia, at a time when the neurodivergence was little understood, he left school with just one O-Level, in art.

Aged 16, he quickly found his way into the world of work, taking a first job at a Fiat garage before becoming a paraffin-delivery man for a local hardware store. This is where things began to click. “I’ve always loved work,” he says. “Suddenly, I didn’t have to read or remember things – I got paid to just do stuff and talk to people.”

That bias for action – combined with ambition and an appetite for responsibility – has defined his rise at Kurt Geiger. It also shaped how he led through the pandemic and why he has tied the brand’s next chapter to the American accessories giant, Steve Madden. For British business leaders, his story is a reminder that resilience, speed and clarity of goals often matter more than traditional pedigree.

Retail as a university

Clifford found his edge young. After his string of early jobs, a sales role in the Burton menswear department at Debenhams provided the first rung on his ladder upwards. “I discovered that I was a good salesperson,” he says, quickly became the highest performer in the store. This knack for sales was paired with the confidence which led him to approach Ralph Halpern (chief executive of the Burton Group and founder of Topshop) on a visit to the store and ask him for pointers on how to grow and develop in his career. “Move to London,” was Halpern’s advice.

This he did – applying for the role of store manager in Burton’s Woolwich branch, where he did so well he was quickly promoted to head up the biggest store in the company, in Bromley, and lead a team of 30 staff.

I’m sort of annoyed that we’re not educating 100 young people every six months.

Clifford is candid about where he had set his sights early on. “I have a load of self-motivation and energy,” he says. “I always wanted to be the boss.” That clarity can unsettle some managers when it shows up in a 20-year-old. In Clifford’s case, it brought focus and results.

The move to the two-floor flagship was Clifford’s first real step away from pure retail management and towards leadership. “That was the moment I realised: crikey, I can’t do this all on my own. I’m a leader of people, I’ve got to get a bit more organised.” The scale demanded new habits and systems.

To get into this new leadership mindset, Clifford – who never enjoyed traditional management books – started reading the Financial Times every day to keep up with what was happening in the business world. He also leant on a long-time habit of writing down lists of his big goals. “From the time I left school, I would always write a list of my dreams,” he says. “I’m a big dreamer.” These included becoming a director by 30 and always earning more than was usual for his age. What made the dreams stick was discipline. Like many leaders, Clifford is an early riser, a habit he formed during his time at the Burton Group. “I would always be the first person at work – I love the feeling that I’m ahead, that secret little time of 5:30am is my favourite.”

His attitude and aptitude got him noticed by Kurt Geiger and he joined the brand in 1995 as retail director, working his way up to become CEO in 2003. He has since steered the company through four sales by Kurt Geiger’s private equity backers and through some significant ups and downs.

Covid: when kindness becomes strategy

Before 2020, prior to the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, the company had enjoyed years of steady growth. Lockdown changed everything. “We went from £41m EBITDA to £6m overnight.” Clifford is naturally optimistic, but even he calls it the worst period of his career. The choices he made then now define the brand’s culture.

Clifford and the rest of the board all gave up their salaries and the company supported staff and communities. “We topped up furlough to all of our employees and motivated our staff to go out and help in the community.” This drive to give back, combined with a chance conversation, sparked what would become a new chapter in Kurt Geiger’s operations. Clifford’s niece is a nurse at a hospital in Portsmouth. During one lockdown chat, he asked her if she needed anything and she quipped back “Ooh, some handbags would be nice!” Sick of sitting at home powerless, Clifford decided to drive to the warehouse, collect 50 £150 gift cards and distribute them to the nurses at his niece’s hospital. This was eventually an initiative they rolled out to every hospital in the country where Kurt Geiger has a store.

The initial act was spontaneous, but it had real commercial and reputational impact. “We got known for doing something radical, doing something positive, making people smile.” There was a positive impact internally too, says Clifford. “The company got better because we became less scared and more creative. We did five years’ worth of strategy work in about 18 months.”

Why Steve Madden and what success looks like

Post-pandemic, Clifford wanted a partner that would help the brand maintain momentum. The answer was a long-standing ally. “We’ve known the Steve Madden team for 20 years,” he says “We knew that they would understand the business, would have the same ambitions as us and they’re good at some stuff that we’re not incredibly good at, such as logistics and supply chain.”

I have a load of self-motivation and energy. I always wanted to be the boss.

He hopes this new partnership will bring a bit of stability for Kurt Geiger. “Private equity was the making of me – both financially and educationally,” he says. “I had an amazing 20 years with four different firms. The only tediousness of private equity is that every three or four years, you’re for sale.”

Now, with Steve Madden, Clifford has more big goals on his list. “The question now is, how do we get to £1bn? How do we capitalise on the fact that we jumped the shark from being a UK shoe company to part of an international accessories brand? Can I be a contributing factor to getting the Steve Madden share price to $50 by the end of 2027?” With turnover hitting £373m (up 10% from the previous year) in the year ending February 2025 and Kurt Geigers’ momentum and reputation on the up, the outlook is positive.

Build the education you wish you’d had

Clifford has non-business-related goals as well for the next few years. In January 2024, Kurt Geiger launched its Business by Design academy, a programme designed to help students from disadvantaged backgrounds break into the fashion industry. “We’re educating 60 young people every year,” says Clifford. “Young people need a break, they need confidence. I would love to be the education secretary because there’s so much that can be done to help.”

The academy has been formally recognised by the government as an educational facility and costs Kurt Geiger around £3m a year but, for Clifford, this is just the beginning. “I’m sort of annoyed that we’re not educating 100 young people every six months.”

He also makes a point of going into schools and talking to young people of all ages about his career. Last month, he spoke to a group of eight-year-olds in a school in North London. Afterwards, he received a text from one of the school mothers, whose daughter is dyslexic, which read: “She heard your talk and she’s now bouncing around at home saying ‘I’m going to be fine, Mum, I’m going to be a CEO of a fashion company.’”

As it was during the Covid crisis, Clifford has managed to make acts of kindness a strategic driver for the company – both inspiring kids and creating a pipeline of much-needed talent at a time when many businesses are struggling to hire the right people. It’s a bold move but, as Clifford points out, one which is available to any organisation brave enough – and good enough – to take that first step.

When I put it to Neil Clifford that many CEOs follow a similar journey to the top: university, a stint at McKinsey or one of the big four, then a corporate job, he laughs that he is “the yin to their yang.” The CEO of the British accessories brand, Kurt Geiger, could be viewed as the anti-blueprint chief executive. Struggling with dyslexia, at a time when the neurodivergence was little understood, he left school with just one O-Level, in art.

Aged 16, he quickly found his way into the world of work, taking a first job at a Fiat garage before becoming a paraffin-delivery man for a local hardware store. This is where things began to click. “I've always loved work,” he says. “Suddenly, I didn’t have to read or remember things – I got paid to just do stuff and talk to people.”

That bias for action – combined with ambition and an appetite for responsibility – has defined his rise at Kurt Geiger. It also shaped how he led through the pandemic and why he has tied the brand’s next chapter to the American accessories giant, Steve Madden. For British business leaders, his story is a reminder that resilience, speed and clarity of goals often matter more than traditional pedigree.