Many words have been uttered in awe and fear about the impact of artificial intelligence on jobs – but fewer about the labour that fuels AI.

While the generative AI providers promise an automated future, behind the curtain millions of invisible gig workers are busy completing tasks such as software development, data annotation and content moderation to power said platforms, for little money and without basic workplace protections.

These mostly invisible labourers have been dubbed ‘cloud workers‘ by Fairwork, a labour rights project hosted at the Oxford Internet Institute. These workers are largely – although not only – located in the global south, poorly paid even by local standards and have next to no labour rights or recourse over bad behaviour from bosses. Globally, according to the World Bank, there may be 435 million of them.

“We’re talking about a sector in the digital economy where workers are underpaid and don’t have access to basic labour protections,” says Jonas CL Valente, co-lead of Cloudwork at Fairwork, which advocates online workers’ rights. “And because they are competing with people all around the world, it’s a race to the bottom.”

With this ‘planetary labour force’, as Fairwork calls it, even Karl Marx could not have imagined a reserve army of labour so gargantuan. The endless supply of would-be coders, data annotators, translators or those clicking through myriad other ‘micro-tasks’, says Valente, means there will always be someone willing to complete such work for lower pay.

So, on the increasing number of platforms from Fiverr to Upwork and Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, workers in lower-income, emerging or developing economies tend to undercut themselves to compete with workers in even lower-income economies.

Gig work focus is on Uber over cloud workers

Over the past decade, some progress has been made in the UK in providing basic labour protections to gig economy workers offering delivery or courier services. Uber is, for instance, organised under the GMB union, while the IWGB continues to push for the rights of precarious gig workers.

The Starmer government’s Employment Bill amendments address some of the long-running problems around precarious employment. The Trades Union Congress, meanwhile, has proposed an AI bill to protect employees against automation and AI. But all of this focuses either on physical gig work or the impact of AI, rather than those many who, through online platform work, are actually building it.

“We published a policy brief showing platform and cloud work is completely absent from the Employment Bill,” notes Valente. “The government is trying to tackle some issues, such as zero-hour contracts and other problems, but platform work is simply not there.”

Remote gig work is booming in the UK and this is a trend that will likely continue, because AI platforms simply need humans to annotate or categorise their data. “The UK is the second-largest in terms of demand,” says Valente.

The cloud worker index – which platforms are performing best?

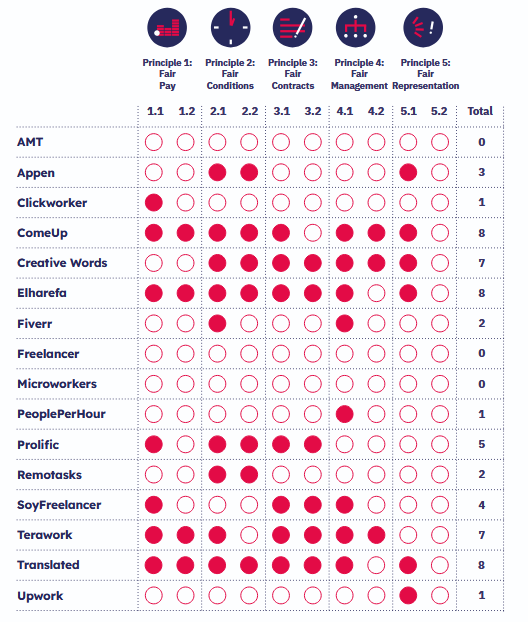

To get around the lack of recourse or labour rights, the Fairwork project has established a framework to scrutinise online gig work and pressure platforms to adopt basic labour rights protections.

In its yearly report, Fairwork scores platforms out of 10 on their ability to meet minimum thresholds on factors including: mitigating precarity, providing communication, due process and appeals channels for punitive action and ensuring workers are paid for completed work, as well as monitoring and addressing health and safety risks. A perfect score of 10 only means that the platform has met Fairwork’s minimum standards of workers’ rights and basic labour protections.

The platforms under the spotlight were picked for either their global reach or their local popularity in certain markets. Among those scrutinised were more localised platforms, such as Elharefa, based in Egypt, or the Spanish-language SoyFreelancer, as well as Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, Fiverr, Freelancer and Upwork.

Mechanical Turk and Freelancer scored a 0 out of 10. Fiverr, just 2 out of 10, and Appen only 3 out of 10. Only four platforms were found to be paying their workers the equivalent to the local minimum wage.

Others, especially those engaging with Fairwork, scored better. This, says Valente, proves that the challenge is not logistical but one of will.

“If you look at the Upwork website, they have dozens of pages of policies, so it’s not for a lack of rules,” he says. “They have dispute-resolution systems, they have payment policies. The issue is that those rules are still not ensuring the minimum standards required of software work.”

Meanwhile, Fairwork found that, on some platforms, about a third of all labour is completely unpaid. That work might involve tinkering with profiles or gaming algorithms to make freelance contractors more attractive or visible to buyers.

Additionally, most workers are under pressure to compete with two opposing ends of the spectrum: the top-10th percentile of well-established platform workers, who win most of the contracts and are paid the most money, and the lowest-paid employees worldwide. The end result is the same: the majority of freelancers struggle to gain work and therefore undersell themselves.

Because cloud workers compete with people all around the world, it’s a race to the bottom

In some of the most egregious cases of unpaid work, says Valente platforms, including Freelancer.com, run a ‘contest’ model where gig workers must complete their tasks first and submit these to the buyer. The buyer then selects the work and contractor they are most satisfied with, while the others go unpaid. “This is a perverse model,” Valente says.

Although the broader picture seems bleak, it’s not all doom and gloom. Some platforms, such as Appen, are engaging with Fairwork to improve pay and conditions. Now, Fairwork has created a certificate that brands can stamp on their platforms to demonstrate they are operating ethically, a little like Fair Trade, but for digital supply chains.

Ultimately, he says, that’ll be better for both gig-work brands and the cloud workers. If these brands stick their head above the parapet and show a commitment to treating their freelancers fairly, more will move over to those platforms and the companies that own them will take home more commission – and profit.

Many words have been uttered in awe and fear about the impact of artificial intelligence on jobs – but fewer about the labour that fuels AI.

While the generative AI providers promise an automated future, behind the curtain millions of invisible gig workers are busy completing tasks such as software development, data annotation and content moderation to power said platforms, for little money and without basic workplace protections.

These mostly invisible labourers have been dubbed ‘cloud workers‘ by Fairwork, a labour rights project hosted at the Oxford Internet Institute. These workers are largely – although not only – located in the global south, poorly paid even by local standards and have next to no labour rights or recourse over bad behaviour from bosses. Globally, according to the World Bank, there may be 435 million of them.