The first step towards fixing something is often to admit it is actually broken. Well, the plastics system is broken.

The problem is big, so the fix must be even bigger. It has to be strategic and ambitious but, most of all, systemic.

It must move society away from the “take, make, dispose” mindset that has long-informed linear consumption patterns and business models, towards a win-win scenario that simultaneously keeps plastics in the economy, but out of the environment. Led by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, the New Plastics Economy is a three-year initiative to build momentum towards a plastics system that works: the fix. And the Plastics Pact is one of its first steps.

It is applying principles of circular economy and brings together key stakeholders to rethink and redesign the future of plastics, starting with packaging. But why packaging?

Why packaging became a main focus for the New Plastics Economy

“The reason for choosing packaging was quite straightforward,” says Sander Defruyt, New Plastics Economy lead at the Foundation. “It is the biggest application of plastics, with about one third to 40 per cent produced going into packaging.

“Especially because of the short lifespan of most packaging, if you also look at the volumes at end of use, it represents almost 60 per cent of that material stream, too.

“On top of that, it is very visible and recognisable. Almost every person on the planet, every single day, comes into contact with plastic packaging.”

The list of leading brands, retailers and packaging companies working towards using 100 per cent reusable, recyclable or compostable packaging by 2025, or earlier, now numbers 14. They are Amcor, Colgate-Palmolive, Ecover, evian, Innocent, L’Oréal, Mars, Marks & Spencer, Nestlé, PepsiCo, The Coca-Cola Company, Unilever, Walmart and Werner & Mertz.

To realise its vision, the New Plastics Economy initiative has launched the concept of the Plastics Pact. The pacts bring together national and local authorities, businesses involved in designing, producing, using and recycling plastics, as well as NGOs, innovators and citizens.

Plastics Pact: a revolutionary first step towards systemic change

The UK Plastics Pact is the first of this planned global network of agreements, led by WRAP (Waste and Resources Action Programme) and launched in April 2018. A second pact is being developed in Chile, with local B Corp TriCiclos.

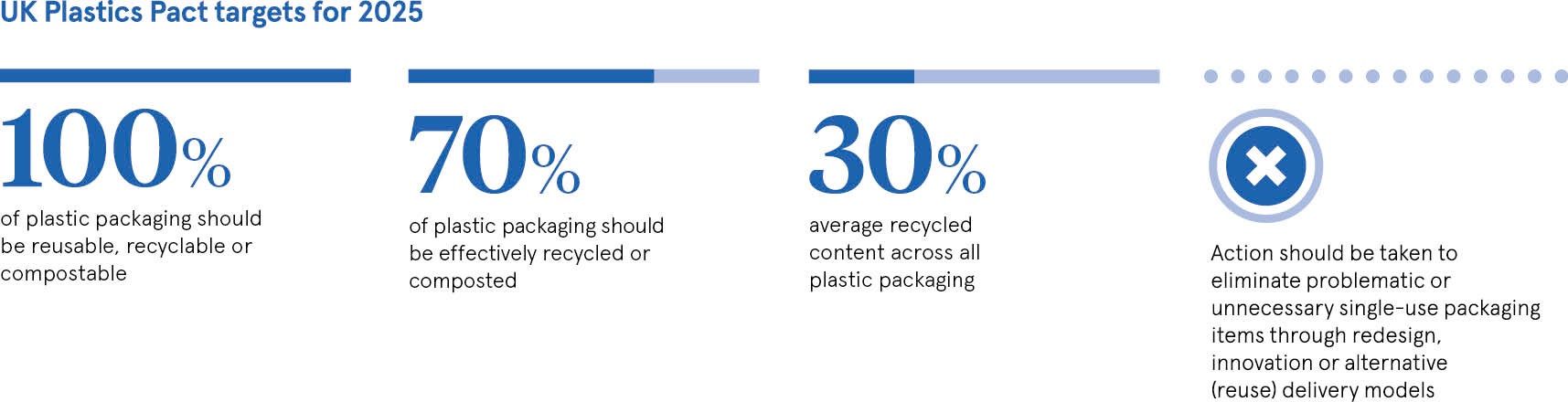

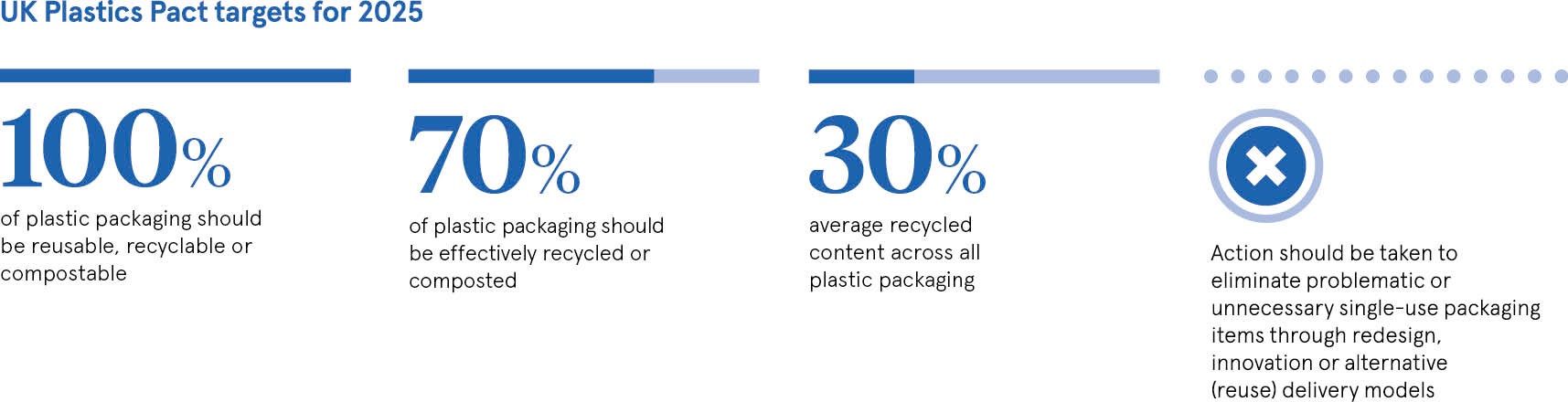

The UK Plastics Pact sets out four big targets for 2025: making 100 per cent of plastic packaging reusable, recyclable or compostable; getting 70 per cent effectively recycled or composted; incorporating 30 per cent average recycled content across all plastic packaging; and eliminating all problematic or unnecessary single-use plastic.

The thing that is really bold and ambitious about the pact is it’s what you call systemic change

“The thing that is really bold and ambitious about the pact is it’s what you call systemic change”, explains Peter Skelton, WRAP lead on the UK Plastics Pact. “It is looking at the whole system moving from linear to circular. The nature of the targets is such that it needs businesses from across the value chain, governments and citizens to help meet them.”

The goals are interdependent and demanding, adds Mr Defruyt. “While each of these targets is important in itself, they are also mutually reinforcing; it is almost impossible to achieve any one of these targets without achieving the others,” he says.

“In addition, they are all really ambitious. The first is 100 per cent and you can’t get more ambitious than that. The 70 per cent means roughly doubling today’s recycling rates and the 30 per cent recycled content probably represents about a fourfold increase.”

Plastics Pact draws in heavyweight members from food sector

The UK Plastics Pact now boasts some 87 members, including all major supermarkets, plus global food and beverage brands, restaurant chains, packaging, waste and recycling companies, from Aldi and Birds Eye, to Pizza Hut, Quorn, Valpak and Veolia.

The government is, of course, part of the system too and plays a critical role in setting the regulatory framework, especially perhaps considering pact commitments are voluntary. As well as providing a necessary legislative push, it can also put in place a catalysing commercial pull, by way of fiscal incentives.

Funding packages to date include £20 million for single-use plastic waste innovation, £25 million for research into marine impacts, £20 million towards developing nations and £16 million for national and city-level waste management, plus introduction of a bottle deposit scheme and consultation into using the tax system to tackle single-use plastics, beyond the existing carrier bag charge.

Reform of the PRN is at the top of the agenda

While pots of money are clearly welcome, for Mr Skelton there are also longer-term strategic alternatives available to government of more intrinsic value. He says: “What is probably more critical is the reform of the PRN [Packaging Recovery Note] system, because that is not currently aligned to drive the behaviour we need to meet the targets. There is no fiscal incentive to use recycled content.”

Mr Skelton is relatively upbeat, though, about prospects for PRN rule changes, given that Environment Secretary Michael Gove has been making positive noises about recommendations submitted by WRAP, working with the Industry Council for Packaging & the Environment and the Advisory Committee on Packaging.

“Having that systemic year-on-year funding coming from the PRN reform is the thing that will be the game-changer. Local authorities can be incentivised and encouraged to collect plastics because it costs them and it costs householders in sorting and reprocessing. The closure of China as an end-market means we need investment in our own capacity,” says Mr Skelton.

“What is really encouraging is that because of the focus on plastics, demand for recycled content is higher than it has ever been. So we need the infrastructure, the sorting, the contracts with local authorities in place to meet that 30 per cent target.”

Plastics should be seen as not only a risk, but an opportunity

Plastics represent not only a risk, but also an opportunity. Reports suggest the global plastic packaging market could be worth as much as $400 billion by 2023. This is an industry with an appetite for growth and investment. It is also a sector ripe for innovation and disruption.

When the Ellen MacArthur Foundation launched a $2-million New Plastics Economy Innovation Prize, together with the Prince of Wales’s International Sustainability Unit, in 2017, the broad base of more than 670 entries was testament to the dynamism of the market. Included on the new business models being pitched was Cupclub, pioneering reusable packaging for coffee and one of the 11 eventual winners.

We need to acknowledge there is a role to play for eliminating problematic and unnecessary items

Reuse business models are underexplored and there could be much more attention paid to how we deliver products to consumers, argues Mr Defruyt. “This is not a recycling story alone. While it is part of the solution, we won’t simply recycle our way out of this problem, neither will we compost our way out,” he says. “We need to acknowledge there is a role to play for eliminating problematic and unnecessary items. There is a role for rethinking business models, innovating and redesigning.”

Plastics Pact members must be aware of all nuances and complexities

The rethinking debate must remain nuanced and avoid blanket plastic bashing or demonising, concludes Mr Skelton. “There is definitely packaging that is unnecessary and problematical, but lumping all plastic into one category is misleading and unhelpful. We have a mantra: ‘There is no bad material, just inappropriate application’,” he says.

Of course, challenges remain, including finding solutions for such things as multilayer packaging or recycled food-grade polypropylene. But there are exciting developments too, such as the groundbreaking demonstration facility for integrating mechanical and chemical recycling at Project Beacon in Scotland.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation has also just announced they are working towards a global coalition of leading businesses and governments that will significantly raise the ambition level of commitments, bolster credibility and drive transparency deeper.

The plastics system might still be broken, but the fix is on.

Why packaging became a main focus for the New Plastics Economy

Plastics Pact: a revolutionary first step towards systemic change