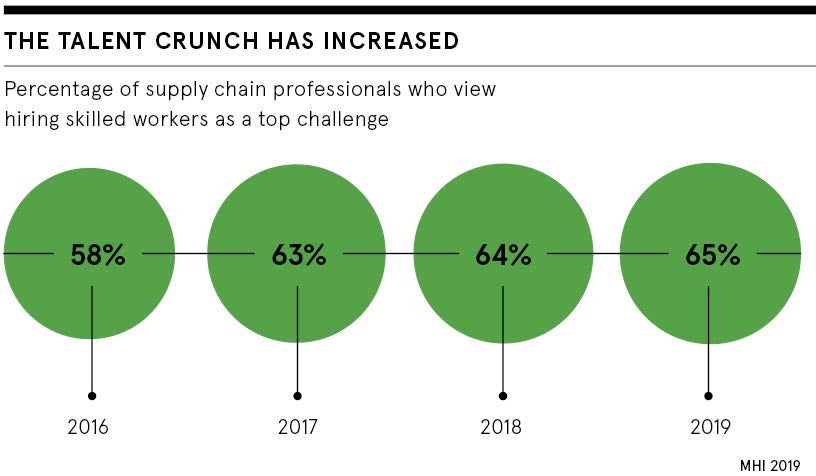

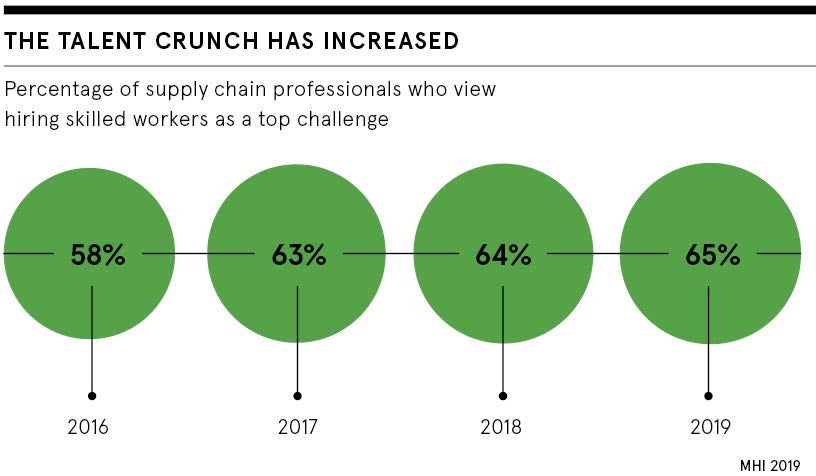

One of the biggest issues facing the supply chain sector, which threatens innovation, is lack of talent. According to recruitment firm Michael Page, the number of adverts targeting procurement and supply chain professionals is 219 per cent higher than the UK average, but these roles attract far fewer candidates.

Supply chain talent shortage is being compounded by an ageing workforce. A UK Commission for Employment and Skills study found just 9 per cent of those working in supply chain and logistics are aged 25 or under, while 45 per cent are over 45.

Brexit is also likely to have an impact, says Lewis Richards, director of WR Logistics, both by reducing the supply of European Union professionals in the sector and increasing demand for workers. “Our own company data has shown a 183 per cent rise in demand year on year,” he says.

It’s no surprise then that a separate study by law firm Weightmans found 25 per cent of managers in supply chain, shipping, receiving and transportation roles, across multiple sectors, highlight the supply chain talent shortage as a key future issue.

Attracting school-leavers and graduate recruits

There are a number of reasons behind the supply chain talent shortage, but a recurring concern is lack of awareness of the profession among younger people.

“School curriculums do not include anything around the supply chain at either GCSE level or A level,” says John Perry, managing director of supply chain and logistics consultancy SCALA. “The result of this is few school-leavers have ambitions to become supply chain professionals and only a limited number will move on to college or university to study the subject.”

Lindsay Bridges, senior vice president of human resources, UK and Ireland, at DHL Supply Chain, concedes that the sector has an image problem. “There is a perception that supply chain is just packing in warehouses,” she says.

“But there are so many more aspects to supply chain management than that. We employ light-vehicle maintenance technicians, HR and finance specialists, engineers and we have recently taken on our first robotics apprentice. The industry is changing and it’s creating new and varied opportunities.”

Leadership development programmes

But Andrew Forrest, principal associate at law firm Weightmans, believes more needs to be done to sell the sector to younger workers. “Working in a stimulating, fast-paced environment and being involved in every phase of a product’s life cycle, from acquisition to distribution, allocation to delivery, can be marketed as an attractive environment to form a launchpad into the industry,” says Mr Forrest.

Employers also need to engage early with young people through either apprenticeships or graduate recruitment programmes, he adds, to help them land the best talent.

Organisations need to do more to attract staff on a personal level, says Beth Morgan, founder and chief executive of boom!, a global community which aims to help women into the supply chain industry, arguing businesses need to go beyond offering a good salary and benefits to stress the potential for a dynamic career path.

“Companies that can offer flexible working conditions are also more likely to appeal to younger generations turned off by the more traditional nine to five, especially men and women with young families,” she adds.

Broader horizons to help talent shortage

There are other groups that can be engaged to help address the supply chain talent shortage. Gudrun Sander, adjunct professor of business administration, with an emphasis on diversity management, at the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland, points out that the vast majority of people working in logistics are men.

“For the more qualified logistic jobs, companies should work on an inclusive culture, equal opportunities and career development programmes for women to use the window of opportunity to fill the pipeline with qualified women for future positions,” she says.

Rob Bales, operating director at Michael Page Procurement and Supply Chain, highlights other groups that can be overlooked. “Returning mothers have traditionally been a group of professionals that many businesses lose and are never able to bring back into their teams, meaning that they will miss out on a wealth of experience,” says Mr Bales. “These professionals represent a huge opportunity to access untapped talent.”

Similarly, those returning from career breaks, perhaps as a result of mental health issues or simply wanting to take time out, can offer firms highly experienced professionals who can return to work reinvigorated.

Procurement and supply chain technology

The situation is being compounded by the need for new skills in areas such as artificial intelligence (AI), automation and digital. “With technology now capable of analysing what has happened and advising on how to react in response, the most important thing for a business is putting supply chain managers in place who are able to analyse and understand the exponential datapoints that are now available,” says Wayne Snyder, head of retail strategy at JDA.

But this, and other emerging areas, can also be useful in attracting people to the sector, which can help overcome the supply chain talent shortage, says Claire Hickling, head of HR at Advanced Supply Chain Group. “Topics such as sustainability, Britain’s EU membership and trading agreements, social media, technology like 5G, the internet of things and AI are all covered by supply chain management and require people with talent in these areas,” she says.

“Supply chains are about much more than just moving items from A to B and we need to tell this to the talent of today and tomorrow. This will help overcome common perceptions that working in the sector isn’t interesting or rewarding and attract future generations of talent.”

Attracting school-leavers and graduate recruits

Leadership development programmes

Broader horizons to help talent shortage