The caricature of elderly Rumpole-style duffers grappling with bundles of papers tied with yards of pink ribbon is the picture that many have of the criminal courts. But that image is rapidly being consigned to the history books.

Squeezed by funding cuts and increasing caseloads, economic necessity has compelled the criminal justice system to embrace the IT revolution in a bid to speed up cases and reduce waste.

In the 21st-century criminal court, iPads replace paper, pop-up venues replace courtrooms and defendants will be able to enter pleas online without setting foot in the dock.

Rising inefficiency

Last year the government spent £2 billion on the criminal justice system, which dealt with 1.7 million offences in the courts. But a parliamentary watchdog warned last month that the system is close to breaking point and failing victims, who face a postcode lottery in getting justice.

The Public Accounts Committee (PAC) said the “overstretched and disjointed” system was “bedevilled by long-standing poor performance, including delays and inefficiencies”.

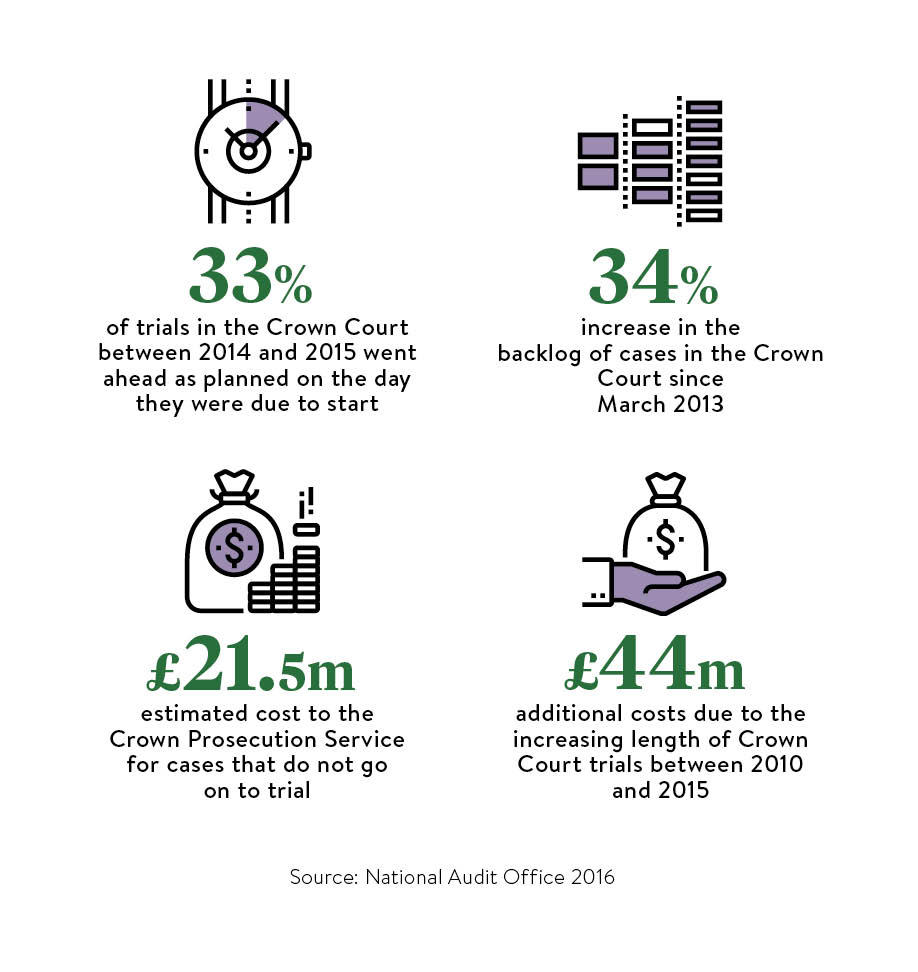

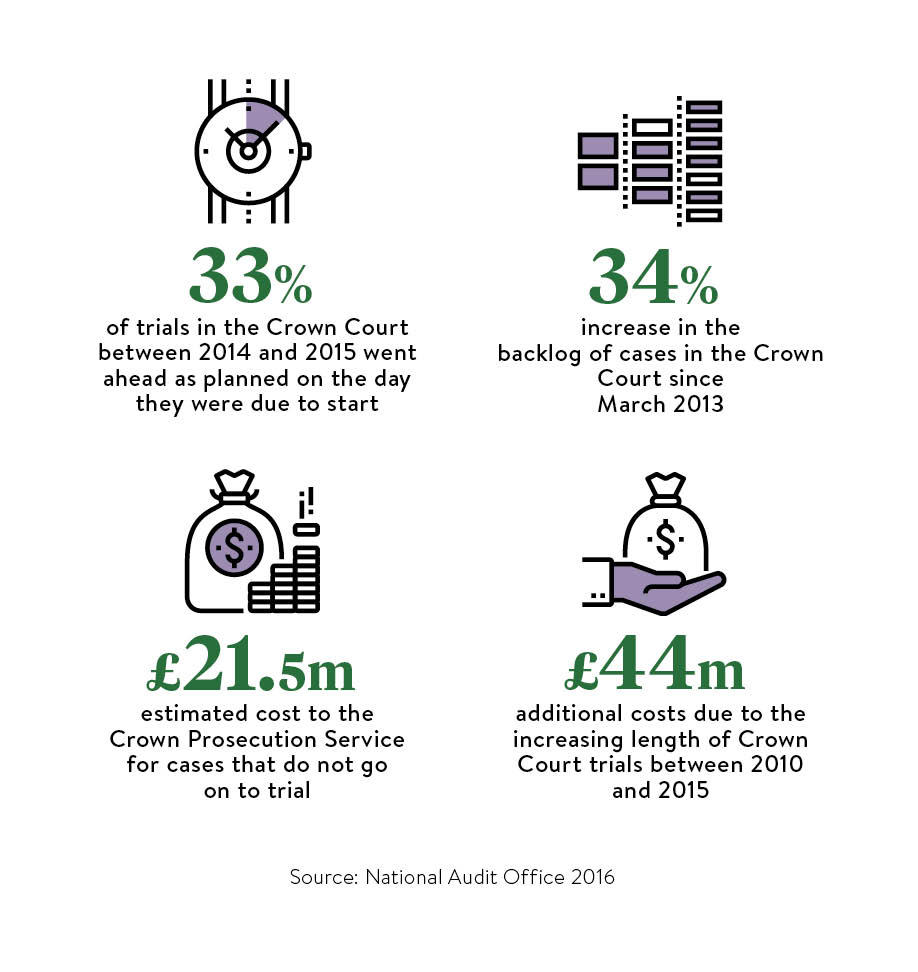

It found that only a third of crown court trials proceed on schedule or at all, which in 2014/15 cost the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) £21.5 million on cases that did not go ahead.

With 26 per cent funding cuts forced on the criminal justice system since 2010/11, coupled with a rise in the number of longer, more complex cases, it is little wonder that it is feeling the strain.

But the inefficiencies existed long before the cuts. Lord Justice Jackson noted in his 2014 review of efficiency in criminal proceedings that the system relies on “a combination of long-standing manual processes and ageing computer systems that have evolved in a piecemeal fashion over many decades”.

Back in 2013, Damian Green, then a justice minister, stressed the need to end the “out-dated” reliance on paper, announcing plans for a fully digital court room by 2016.

“Every year the courts and Crown Prosecution Service use roughly 160 million sheets of paper. Stacked up this would be the same as 15 Mount Snowdons – literally mountains of paper,” he said.

Over the years, the criminal justice agencies have introduced a panoply of initiatives designed to tackle inefficiency, by reducing reliance on paper, enabling digital working and cutting court hearings, to the extent that Lord Justice Jackson reported “transformation exhaustion” in a system “crowded with plans for future development”.

The digital courtroom

The Treasury has committed more than £700 million to modernise the courts and tribunals, in what the PAC describes as an ambitious reform programme.

The plan is now to have a fully connected digital courtroom by 2020, which Her Majesty’s Courts and Tribunals Service (HMCTS) says it is on track to deliver and it estimates will save £200 million a year from 2019/20.

A joint report by the CPS and HMCTS inspectors, Delivering Justice in a Digital Age, notes that progress has been made. More than 90 per cent of cases are transferred to the CPS from the police electronically and nearly all magistrates’ courts are able to receive digitally from the CPS the initial details of the prosecution case.

All criminal courts have wi-fi, widescreens and click-share technology, enabling the prosecution and defence to present evidence digitally.

The crown court digital case system, a web-based digital document tool, has been rolled out for the service and receipt of disclosure and evidence. In addition, HMCTS says progress is being made on the common platform programme, an online case-management system covering the entire process from pre-charge to disposal, giving all parties access to one digital case file.

The first paperless trial, in which jurors used iPads rather than files of evidence, took place in Birmingham in 2013. A handful of others have occurred since, including a large fraud trial last year at London’s Southwark Crown Court.

HMCTS is piloting other initiatives, including “digital mark-up” which immediately records case outcomes and triggers notifications and documents to support or enforce decisions.

Government IT projects do not have a great track record and glitches are already causing headaches

Defendants will be able to enter guilty pleas online for traffic offences following completion of the scheme’s national rollout this month.

The use of video links has been expanded to save the cost of transporting defendants from police stations or prisons to court, and upgraded systems have been installed in 130 courts. In 2014 Judge John Tanzer appeared via Skype at Croydon Crown Court to hear a jury deliver its verdict in a case of a teacher acquitted of sexual offences.

Overcoming challenges

As austerity cutbacks force the sale of court buildings, proposals from law reform group Justice, in its What is a court? report, mooted pop-up courts in public buildings.

All this sounds impressive, but government IT projects do not have a great track record and glitches are already causing headaches.

The Delivering Justice in a Digital Age report, published in April, found that computer systems used by criminal justice agencies did not talk to each other and some parties still relied on paper and manual processes, which lead to duplication of work and an increased risk of error.

It expressed concern that the lack of a reliable method to share information, including CCTV, 999 and interview records, resulted in lost data and concluded the vision of a digital end-to-end system is still some way from becoming reality. The report also questioned how the digital age embraces the unrepresented defendant.

Zoe Gascoyne, chairwoman of representative group, the Criminal Law Solicitors’ Association, highlights annoying bug-bears when the technology fails.

She says wi-fi problems make disclosure at court impossible, magistrates are asked to make bail and sentencing decisions without seeing a copy of the defendant’s record because prosecutors only have it on their laptop, and in some courts prosecutors are unable to send anything directly to lawyers, which means relying on a remotely located third party to monitor e-mails and deal with urgent requests.

In addition, says Ms Gascoyne, prisons often refuse to allow lawyers to use their laptops notwithstanding that the evidence is served in digital format.

Implementation of many schemes, she says, tends only to paper over cracks without putting the basic structure of the system right.

Ms Gascoyne concludes: “The problem with the concept of being fully digital is that the criminal justice system deals with real people.

“It is easy for those outside the system to conjure up exciting plans, but the bottom line is that the criminal justice system is about the victim, the defendant and achieving justice – none of which will ever be digitised and all of which requires a human touch.”

Rising inefficiency

The digital courtroom