A 58 per cent failure rate is really, astronomically, high. If Apple, Sony or Microsoft launched a gadget that failed six out of ten times, it would cause an international corporate scandal. If 58 per cent of diners complained about the food at a new restaurant, it would shut within days, if not hours.

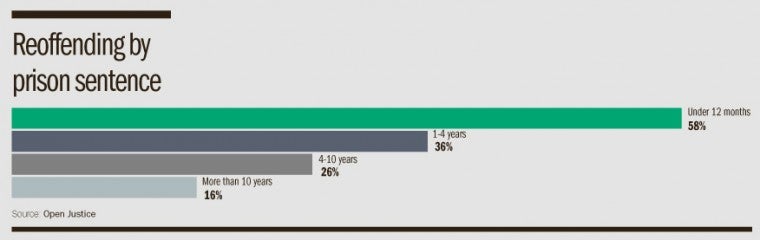

Yet according to official sources, 58 per cent is the proportion of low-level offenders who, having spent under 12 months in prison, are subsequently prosecuted for a new offence. Whether you think this represents systemic failure or not will depend on whether you think prison is for punishment or rehabilitation, or both.

But for the record, rehabilitation is – at least officially – the keystone of the UK’s penal system. The government’s Open Justice website states: “Punishment is pointless if prisoners go on to offend again when they are released.”

Punishment is not devalued or less good, but pointless if people don’t learn their lesson. Yet next to this very reasonable statement, the government website tacitly acknowledges that punishment for so-called lesser crimes is actually 58 per cent pointless.

It is 36 per cent pointless for people serving one to four-year sentences and 28 per cent pointless for those on four to ten-year terms. It is even 17 per cent pointless for people serving stretches longer than a decade even though the window for reoffending is that much shorter.

If prison is the solution, what’s the problem? If the point of prison is to stop serial offending, perhaps by demonstrating to would-be career criminals that getting caught is too high a price to pay, then the statistics show it is pretty ineffective in its remit.

CAUSE OF REOFFENDING

Worse, there is evidence to suggest prison plays a major role in reoffending, not by dragging rates down, but by forcing them up. Frances Crook, chief executive of the Howard League for Penal Reform, says prison is not a weak solution to serial offending, but its cause.

Prison is a horrid place. Violence, drugs and mental illness are commonplace across the board, even in lower category and youth lock-ups. Most people do not come out restored and enlightened, ready to make peace with the world, but brutalised, haunted and addicted.

They have new “friends”, new ideas and a dimmer outlook on a life of legitimacy. They have fallen to the bottom of the public pile, and the odds of them making a positive contribution through work and family are significantly worse than before they went in, such is the stigma attached to ex-cons.

“People find it nearly impossible to get a job upon release from prison and they have a good chance of becoming homeless,” says Ms Crook. “A lot of petty serial offenders come from chaotic backgrounds, but ironically only those serving long sentences can expect help when they leave prison.”

Ms Crook cites the example of someone with a mild mental illness who exposes themselves in public; they can expect to receive up to two years in prison and a permanent place on the sex offenders’ register. In terms of life’s opportunities, that’s game over.

Prison should be a last resort for the worst offenders and alternative treatments employed for petty criminals.

COST OF REOFFENDING

The reasons for this are financial as well as societal. Government figures for 2013 show it costs more than £22,000 to hold a prisoner and a further £22,500 to provide a place in a category C prison – where the risk of escape is low – for a year.

Prison should be a last resort for the worst offenders and alternative treatments employed for petty criminals

Factor in the cost of processing and convicting a criminal, and first-year costs spiral to more than £60,000. The cost of a single 12-month stretch would, therefore, cover the full-time salaries of two probation officers.

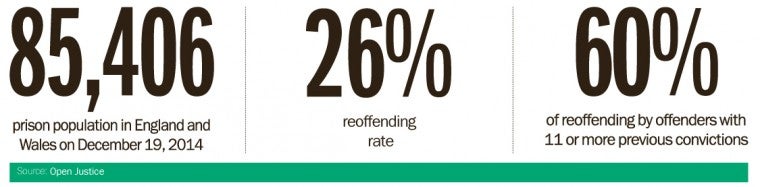

Higher-category prisoners cost more to house and the UK’s prison population is currently hovering around the 85,000 mark. You don’t need to be good at maths to understand that incarcerating people is an expensive business, especially if you have to do it again and again.

“We are spending hundreds of millions of pounds using prisons inappropriately and then trying to mop the mess up afterwards,” says Ms Crook. “Instead of spending money on new prisons, ministers should be investing in preventative measures and community support.

“The savings would be enormous and money could go towards prevention services that are tailored to the individual, health and addiction services, as well as softer prevention measures, such as youth schemes and more street lighting.”

At the heart of the problem, Ms Crook says, is a programme of privatisation that started in the early-1990s and has snowballed through successive governments. Most recently, the probation service was privatised, with contracts handed to non-specialist companies.

This has resulted in mismanagement and arbitrary decisions causing a comedy of errors, she claims. Labour has committed to taking the probation service public again, should it win the election in May, but it will have to pay hundreds of millions in compensation to do so.

“Crime has gone down dramatically in recent years,” says Ms Crook. “Reoffending is the new problem and in order to solve it we must target people who commit low-level crime. This is highly skilled work and it can’t be contracted out to the highest bidder.

“Ken Clarke [former Justice Secretary] understood this, but he was sidelined and his positive steps have been reversed. Now the focus is on people lying on bunks with staff cuts meaning fewer people looking after them.

“The opposition to reform is ideological. It is not party political, but it is within government. All the professional prison and probation services are calling for change, but successive ministers have refused to listen.”

CAUSE OF REOFFENDING

COST OF REOFFENDING