When a 200-metre section of the A10 motorway flyover, known as Italy’s Brooklyn Bridge, collapsed in August, killing 43 people, it didn’t take long for people to suspect mafia involvement. Italy bears scars from the infiltration of organised crime in construction during the 60s, when mafia families managed to win building contracts during a boom period.

It’s quite a lucrative and relatively low-risk area for these fraudsters because it’s not as high profile as other organised crime

In areas of Italy where there is a heavy mafia and organised crime presence, scores of bridges and tunnels are under investigation concerning the use of unfortified concrete. This material contains higher amounts of sand and water, and a lower proportion of concrete, than regular cement and as such poses a risk to the integrity of the infrastructure projects involved.

While some activities concerning organised crime in construction include using cheaper, less safe materials to reap bigger profits, many focus on the less well publicised industry of modern-day slavery, which exploits migrant workers.

How organised crime operates in UK construction

Organised crime in construction is not solely a problem for Italy and the building industry in the UK is far from squeaky clean, where human trafficking is a real concern. A report in April from charity Focus on Labour Exploitation, or FLEX, found that 50 per cent of migrant workers from eastern Europe had no written contract, with 36 per cent saying they hadn’t been paid for work completed or didn’t understand all the deductions on their payslips.

These workers are often lacking necessary skills and competences that make them safe to work in construction environments. Abuse of systems requiring qualifications and training is, of course, partly how organised crime makes its money.

Ian Sidney, fraud investigator for the Construction Industry Training Board, says organised crime gangs try to produce fake qualifications, or even infiltrate the testing process, to get illegal and/or trafficked workers issued with the documents needed to be allowed on to construction sites.

“Organised crime groups are trying to infiltrate the testing and training of candidates,” he says. “It ranges from people doing tests on behalf of other people, right through to people paying [for fake cards].”

Illegal construction workers given fake documents and no training

Mr Sidney says workers arriving illegally will often have to pay criminals for a package that includes ID, such as fake passports and competence cards, on arrival to the UK, which feeds the problems of modern trafficking, human slavery and the debt bondage.

In February, a gang of seven men were jailed for a combined total of 16 years after being found guilty of the widespread distribution of fake British passports, residence permits and Construction Skills Certification Scheme (CSCS) cards.

“It’s quite a lucrative and relatively low-risk area for these fraudsters because it’s not as high profile as other organised crime,” says Mr Sidney. The men at the centre of this investigation were found to have charged £200 for CSCS cards and £900 for passports.

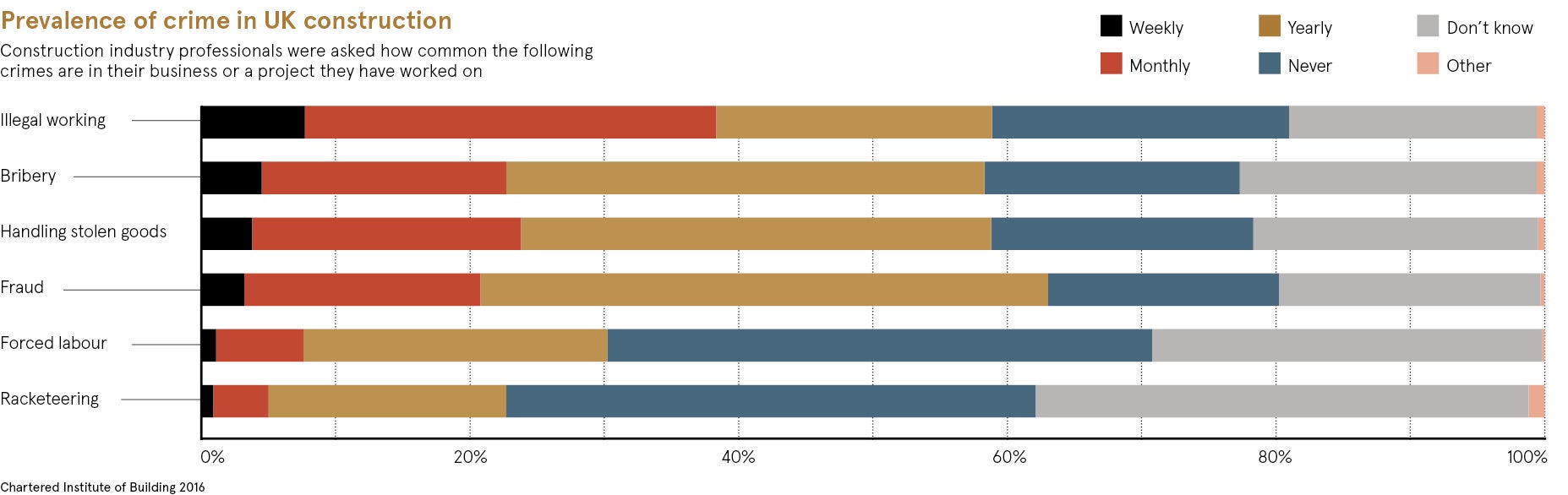

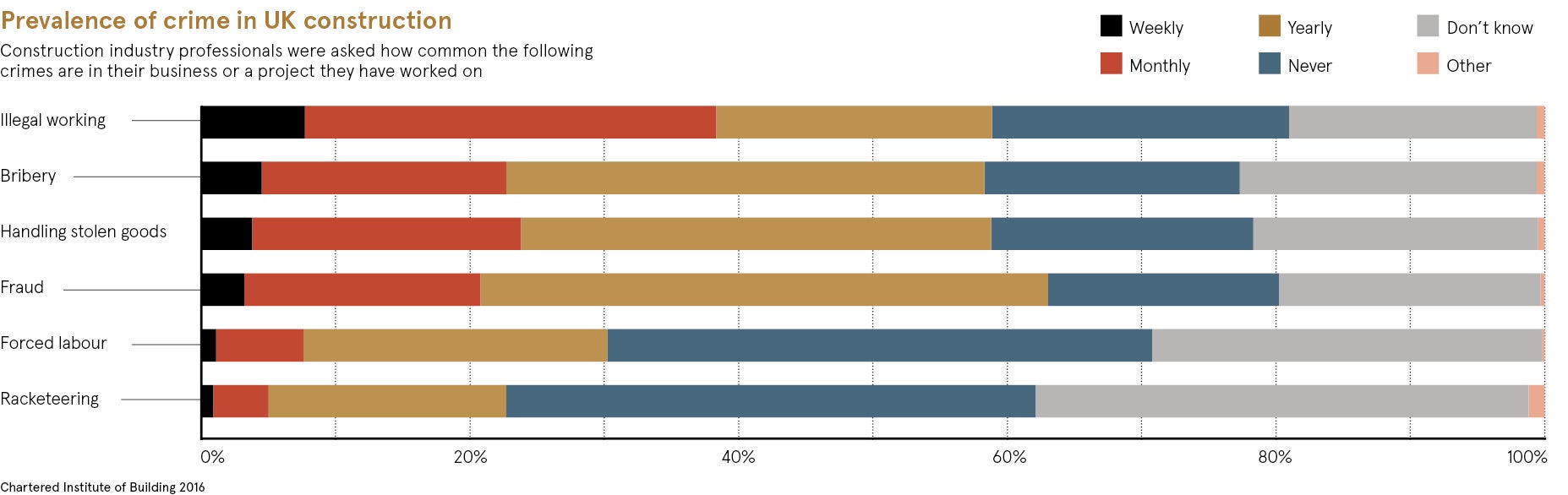

Other issues around corruption and organised crime also pose problems. David Barnes, public affairs manager for the Chartered Institute of Building, says half of all respondents in a survey reported that corruption in the construction industry was common.

“Corruption in construction is listed as one of the biggest industries that the National Crime Agency wants to tackle in terms of organised crime,” says Mr Barnes. “It’s such a big industry. I don’t think people realise its not just people working on site; it’s a lot of the project management stuff that goes on.”

New technology sniffing out organised crime in construction

Luckily for the construction industry, technology has advanced to a point where men on the gate now have some useful tools to help check that people are who they say they are.

“Some of the tactics we would use would be smart cards and chip and PIN so employers can use card readers and card checkers to first see if they are genuine,” says Mr Sidney. He explains that some bigger sites use document-scanning and face-recognition technology to make sure the person presenting the ID is genuine.

“We saw it done with identical twins and they presented each other’s passports,” he says. In this instance, the documents were scanned and shown to be genuine, but the faces, while similar enough to pass a check by the naked eye, were not good enough to fool the technology.

Biometric identification isn’t the only tech helping to keep construction sites secure. Drones are useful for aerial surveillance, using regular and infrared cameras, while advanced GPS services can be used to track movement on a work site. However, while technology is helping companies bolster their resistance to organised crime in construction, experts say it is incumbent on firms to address internal issues too.

“I believe more businesses in the construction sector need to be vocal about ethical challenges [the industry] faces, whether that’s bribery, corruption, health and safety or modern slavery,” says Mr Barnes.

In a post-Grenfell Tower world, where the construction industry is accused of allegedly cutting corners with disastrous consequences, the industry must face its problems head on. “We are witnessing an appetite for change,” Mr Barnes confirms.

How organised crime operates in UK construction

Illegal construction workers given fake documents and no training