When the world’s biggest advertiser warned the digital media supply chain is “murky at best, fraudulent at worst”, it rang alarm bells in boardrooms and marketing departments around the globe.

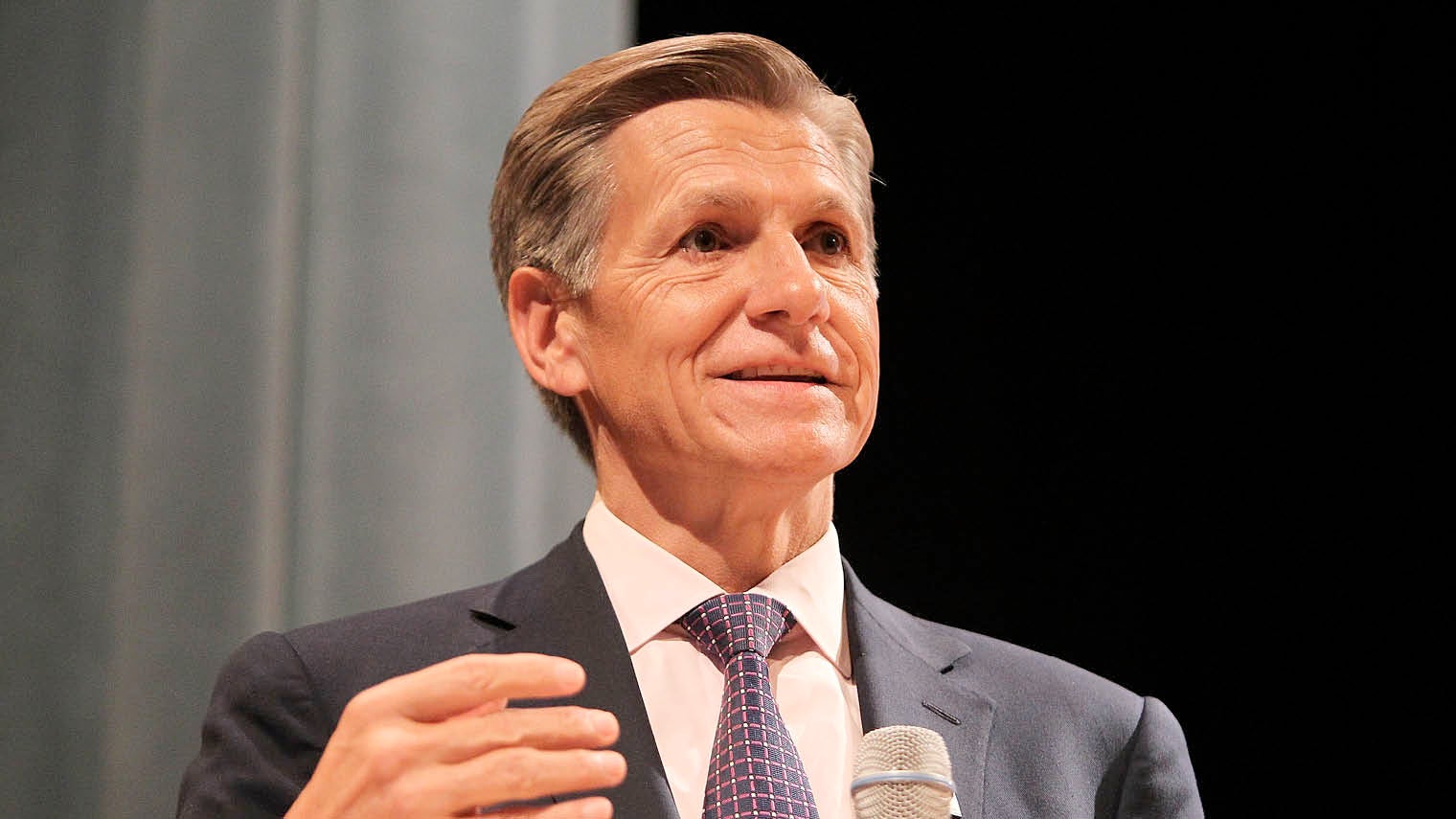

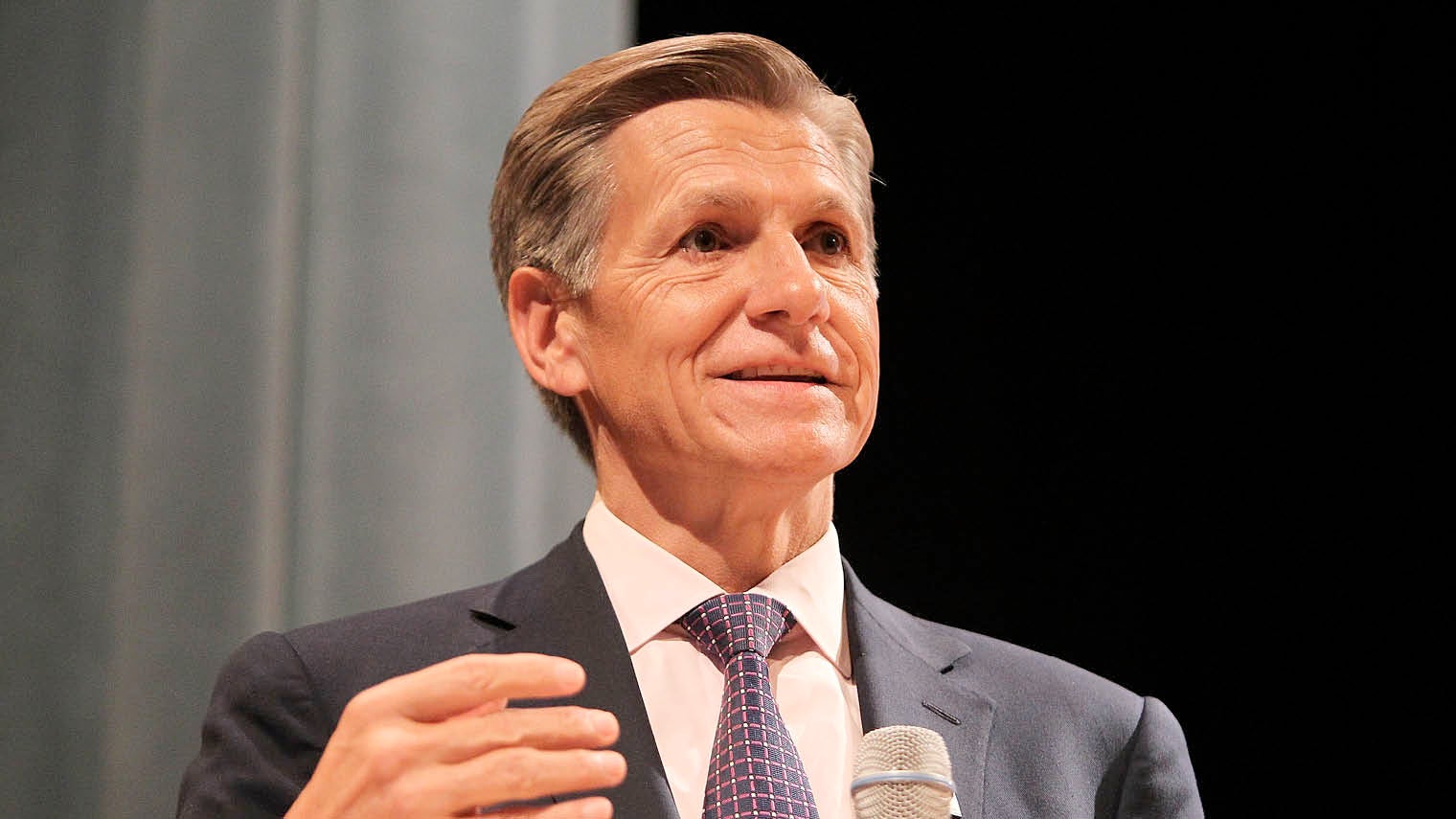

Marc Pritchard, chief brand officer of Procter & Gamble, made the comments in a landmark speech to the US internet industry in January 2017 and, nearly two years later, fears about marketing fraud have only increased, even if awareness of the problem has also risen.

It should be in the interests of all the players in the media supply chain – advertisers, their agencies and other intermediaries, internet platforms and publishers, regulators and law enforcement – to clean up the digital ecosystem.

But it is hard to keep up with criminals who exploit the global nature of the internet and are always seeking to stay one step ahead of the law, particularly as technology continues to evolve rapidly and constant vigilance is required.

Marc Pritchard, chief brand officer of Procter & Gamble, says the digital media supply chain is “murky at best, fraudulent at worst”

Marketing fraud costing billions, and it’s on the rise

Juniper Research has warned that marketing fraud will cost advertisers an estimated $19 billion (£15 billion) and rising in 2018, close to 10 per cent of global digital ad expenditure.

The research firm identified the main problems as fake websites and internet domains, fake accounts, and bot farms that generate fake views by robots, not people.

The main problems are fake websites and internet domains, fake accounts, and bot farms that generate fake views by robots, not people

Mobile is the new battleground. Ad fraud on mobile devices has jumped eight-fold in the last year as smartphone use has increased and desktop fraud has come under greater control, according to Double Verify, a company that helps advertisers to check their media and marketing spending.

Mobile app “spoofing” and “hidden” ads that are “fraudulently diverting brand investments” are among the problems cited in DoubleVerify’s 2018 Global Insights Report.

The measurement company also warns that brand safety “violations”, where ads appear next to inappropriate content, have risen 25 per cent this year because of a “surge in fake news and unsubstantiated content”.

Media supply chain comes under fire

Marketing fraud has also become a political issue, after evidence emerged that bad actors from outside the United States tried to influence the outcome of the 2016 US presidential election by micro-targeting audiences with messages, some of which contained dubious and fake claims.

Other areas of the media supply chain have come under scrutiny, even though some players may be guilty of “murky”, rather than “fraudulent”, behaviour.

Automated ad-buying, known as programmatic trading, has raised concerns because there are lots of intermediaries that may be taking a cut in the supply chain, as the money passes through advertising exchanges, which aggregate buyers and sellers of ad inventory. Some advertisers have found that when they spend £1 on digital media as little as 30p is reaching the publisher.

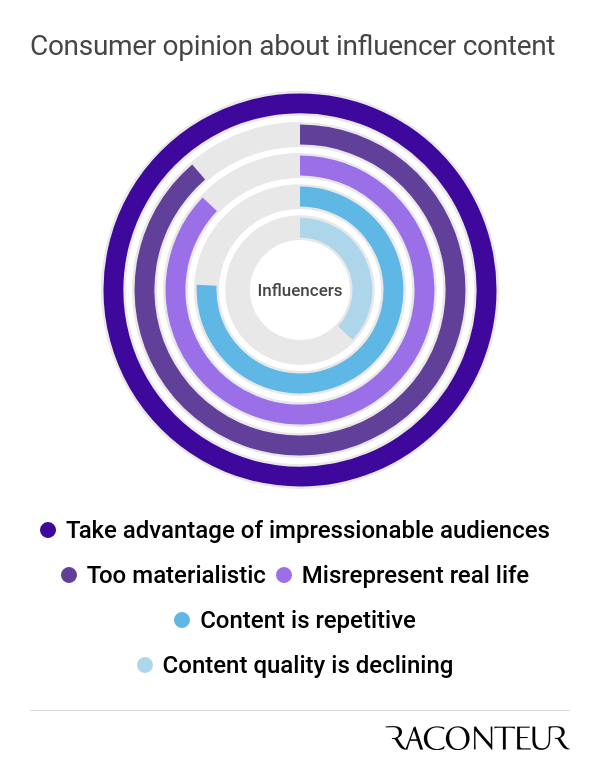

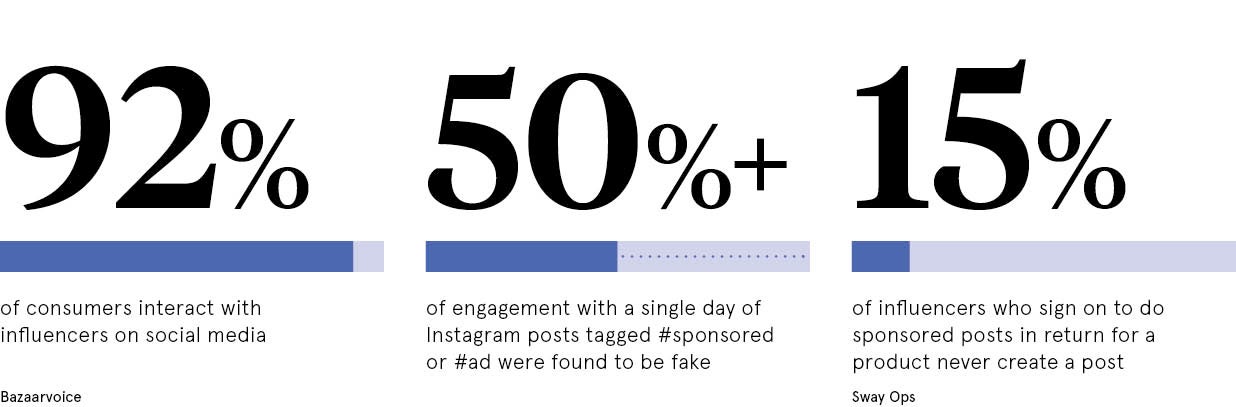

Brands have also raised questions about affiliate marketing, where third parties receive a cut for driving ecommerce sales, and influencer marketing, where brands pay social media influencers to endorse products.

Important not to lump all issues together as “fraud”

MPs on the Commons Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) select committee have suggested the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) could investigate fake accounts to see if advertisers are being charged for reaching an audience that doesn’t exist.

Advertisers have faced similar problems with viewability, being charged for ads that can’t be viewed properly or are viewed by bots.

The digital media ecosystem does indeed look murky. However, Martin Vinter, head of media at Ebiquity, a UK-based consulting and media auditing firm that advises hundreds of global advertisers on their marketing spending, says it may not be helpful to lump all these different areas together under the catch-all phrase “marketing fraud” or “advertising fraud”.

“It’s an umbrella term for many different things,” Mr Vinter says. “We’ve slightly skewed the conversation to fraud.”

He believes it’s important to distinguish between fraudulent and criminal behaviour, such as website or app spoofing at one end of the spectrum, and lax or poorly defined standards around viewability at the other end.

Advertisers take tackling marketing fraud into their own hands

The ad industry has functioned for many years through a system of self-regulation and the law is notoriously slow to catch up with technology. So advertisers may still be best placed to take responsibility for cleaning up what Keith Weed, chief marketing and communications officer of Unilever, the world’s second biggest advertiser, calls the “digital swamp”.

Mr Vinter believes advertisers have been making progress in tackling the supply chain. “Affiliate marketing used to be a Wild West until people started to take control,” he says, explaining how third-party verification of online activity has brought independent accountability in recent years.

Similarly, programmatic trading has begun to clean up its act after intense scrutiny.

Advertisers have been tightening up their contracts with agencies, demanding that intermediaries disclose how much each of them might be taking as a cut or getting as a rebate, and doing direct deals with the big tech platforms such as Google and Facebook.

Publishers have also introduced ads.txt software that identifies authorised buyers and sellers on advertising exchanges to combat the problem of domain spoofing and fake clicks.

Verification is crucial

“Unauthorised” buyers who act as intermediaries on behalf of advertisers and charge for ads that never appear is a serious problem.

The Guardian and Google carried out a joint test on the newspaper publisher’s inventory this summer when they bought display and video ads without using ads.txt. They discovered that some unauthorised ad exchanges were charging for ads on The Guardian yet no ad appeared and no money reached The Guardian.

An astonishing 72 per cent of video ad spend that The Guardian bought in its test without ads.txt was going to unauthorised exchanges.

Mr Vinter says advertisers and publishers are waking up to the need for more third-party checks and verification to monitor marketing investments. “Verification is the panacea,” he believes.

Tightening up standards for influencer marketing

Influencer marketing is another minefield in need of tougher standards. Unilever’s Mr Weed told the ad industry’s annual festival, Cannes Lions, in June that urgent action is required to tackle problems such as influencers “buying” followers.

Facebook and Twitter have both come under pressure to shut down fake accounts. At one stage, Twitter was suspending as many as one million accounts a day earlier this year.

“Influencer marketing is probably now in the place where affiliate marketing was,” Mr Vinter warns, adding that lack of verification standards could potentially pose more harm to a brand’s safety because of the reputational risks of partnering with a dishonest influencer.

The awkward truth for brands is that the digital ecosystem is complex and fragmented, and they can’t tackle marketing fraud in isolation.

The awkward truth for brands is that the digital ecosystem is complex and fragmented, and they can’t tackle marketing fraud in isolation

As Wayne Gattinella, chief executive of DoubleVerify, says: “It’s critical that digital marketers around the world have a holistic approach to brand safety, digital ad fraud and viewability.”

Does marketing fraud need its own legal investigation?

There are signs that regulators and politicians are helping to apply pressure.

Sharon White, chief executive of Ofcom, the UK’s communications regulator, believes “the argument for independent regulatory oversight” of tech companies “has never been stronger” when it comes to fake news and disinformation.

The Commons DCMS select committee has already published a report that was scathing about Facebook and Cambridge Analytica’s misuse of data, and is planning a follow-up study of flaws in digital advertising.

The unanswered question is whether the CMA in the UK, the US Department of Justice or another law enforcement body will launch a legal investigation into marketing fraud.

But the immediate responsibility should rest with advertisers because it is their money. They have the greatest power to demand change from agencies, publishers and internet platforms by refusing to spend with anyone unless they are accountable and transparent.