Intellectual property (IP) crime is a thorn in the side of British industry. Some 480 people were successfully prosecuted for patent, copyright or trademark infringements in 2016, according to the most recent government IP Crime and Enforcement Report.

The report, released in September 2017, notes that 433 people were found guilty of offences related to the Trademark Act and a further 47 under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, during the previous year. While this was marginally down on 2015 totals of 490 and 69 respectively, it again highlighted the vulnerability of corporate IP assets to opportunist criminals.

Although the figures may look startling, companies may be about to gain the upper hand in the battle to protect patents, trademarks and licences from fraudsters. The solution, it seems, is from the much-hyped, but lesser understood, technology of blockchain.

In the simplest of terms, blockchain allows many parties to work on one central database. Once a transaction is entered on the database, it is unable to be altered or updated by anyone else. While applications for this technology are widespread, the implications for IP are significant, according to experts in the sector.

“The main benefit of blockchain is that it is distributed, accurate and immutable, so you can’t overwrite what is there,” explains Richard Tatham, a patent attorney at IP rights law firm HGF.

“Compared to other hype words that you hear now, such as artificial intelligence and quantum computing, I think blockchain has a lot more near-term relevance, in terms of intellectual property and elsewhere.”

If the concept of this modern technology is tricky to grasp, the scope for blockchain is perhaps better illustrated through the applications already playing out in industry. In the music industry, for example, it is already being adopted to crack down on piracy, and to improve tracking of distribution and revenue.

Simon Jupp, an associate in Taylor Wessing’s IP and media team, explains that artists have been struggling in recent years to track who is using their music and monitor the associated revenues.

Simon Jupp, an associate in Taylor Wessing’s IP and media team, explains that artists have been struggling in recent years to track who is using their music and monitor the associated revenues.

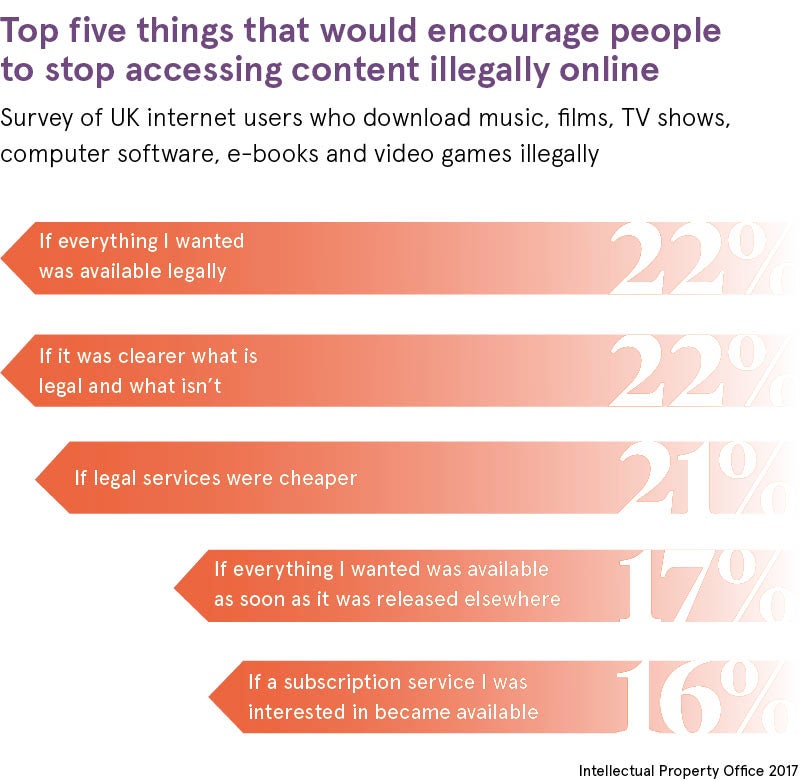

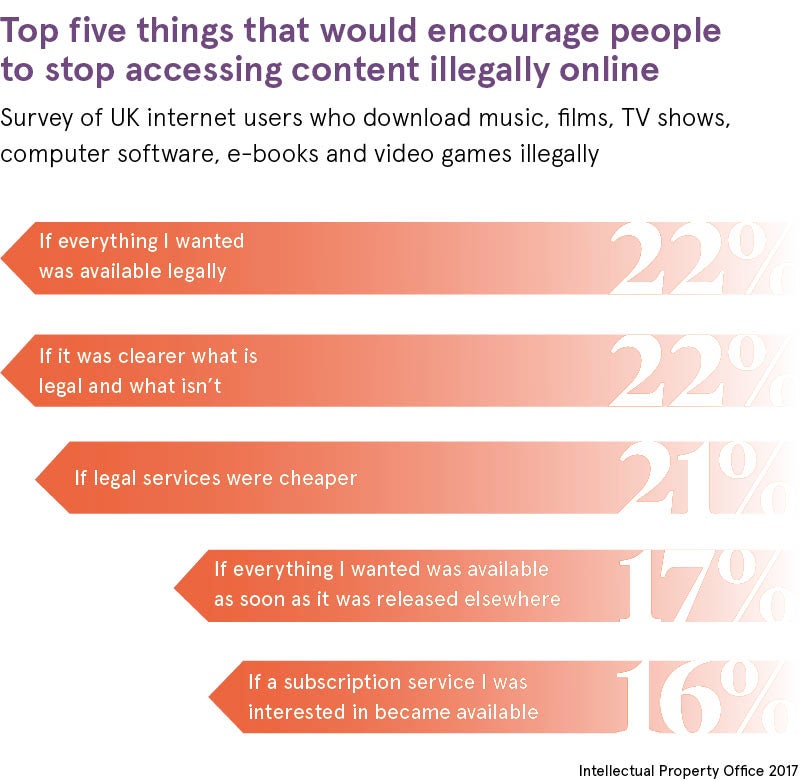

Mr Jupp’s comments are underscored by a 2017 report from the UK’s Intellectual Property Office, which found that 6.7 million or 15 per cent of UK internet users consumed at least one item of online content illegally during the first quarter of 2017. However, he believes that artists, producers and songwriters are waking up to the potential in blockchain technology to keep better control of their work.

“One bold thing would be for artists to not have the need for streaming services or record companies and publish their own works, and track use and remuneration themselves,” he says.

A British singer-songwriter is doing just that and in doing so Imogen Heap has become as well known for her pioneering approach to music distribution as she has for the music itself.

In 2017, she spoke out in the Harvard Business Review after a rival artist was accused of stealing her copyright. As a result, the artist had his material removed from a prominent distribution site for using a 30-second sample of her work.

Ms Heap said her record label had probably used an over-eager robot to monitor potential infringements. She said situations like this could be avoided in future, however, by embracing blockchain technology for rights and payments. Since then she has encouraged musicians, producers and recording artists to take inspiration from her online platform, MyCelia, which uses blockchain to clarify who has the right to use samples and tracks listeners, rights and authorised distribution.

Despite the widespread attention that members of the music industry have captured through backing blockchain innovation, there are those who believe the best application of the technology for IP purposes has yet to be identified.

It is fast moving, but it is difficult to say what the landscape will look like in five or ten years’ time

“We are at an early stage for most areas of blockchain technology,” says Philip Horler, patent attorney and senior associate at Withers & Rogers. “It is fast moving, but it is difficult to say what the landscape will look like in five or ten years’ time.”

Mr Horler acknowledges the widespread hype around creative solutions like those of Imogen Heap, but suggests a more practical application for the technology might be in supply chain tracking to prevent the counterfeiting of goods.

“The general principles are fairly clear. If it is possible with blockchain to record an individual item at the very start of the supply chain, each time that item changes hands, it can be recorded on the blockchain by each party,” he explains.

Mr Horler cites blockchain group Everledger as an example of a trailblazer. The company specialises in tracking valuable assets, such as precious stones, using blockchain, smart contracts and machine-vision. This, he says, could have a significant impact in the fight against counterfeiting.

“For diamonds, it means you can be satisfied the diamond is not a blood diamond, that it has a good history. It is doing something that has not been done before and it could be quite useful in preventing counterfeiting,” he says.

While Mr Horler acknowledges the system is reliant upon the different parties updating the blockchain ledger, he still believes the potential to reduce counterfeit crime is huge.

“I would be amazed if we didn’t see some fraudulent behaviour around blockchain, but the technology, from a technical perspective, is pretty strong,” he concludes. “It is currently very difficult to modify, to the point of being practically impossible. How easy it is to act dishonestly will come down to how it is set up and how it is utilised.”