Law enforcement, security vendors and white hat hackers all collaborate in the fight against cybercrime. It would be naive to imagine that cybercriminals are not meeting this challenge in kind. Yet far too many organisations seem to think that the dark side of the internet is still inhabited by teenagers in hoodies looking to make some beer money.

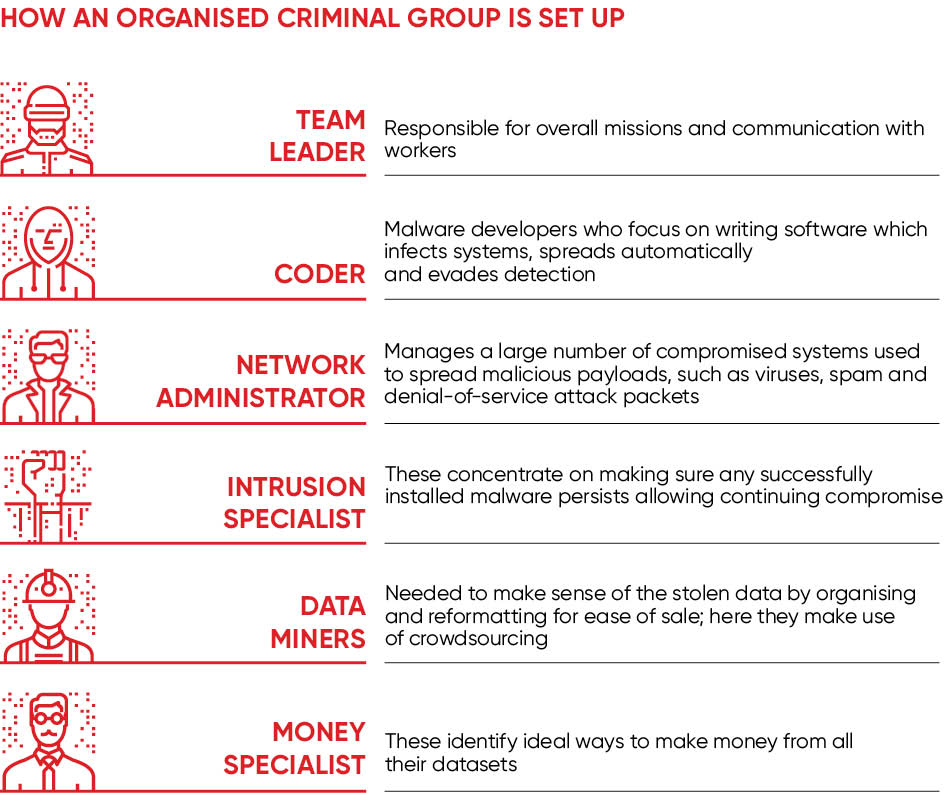

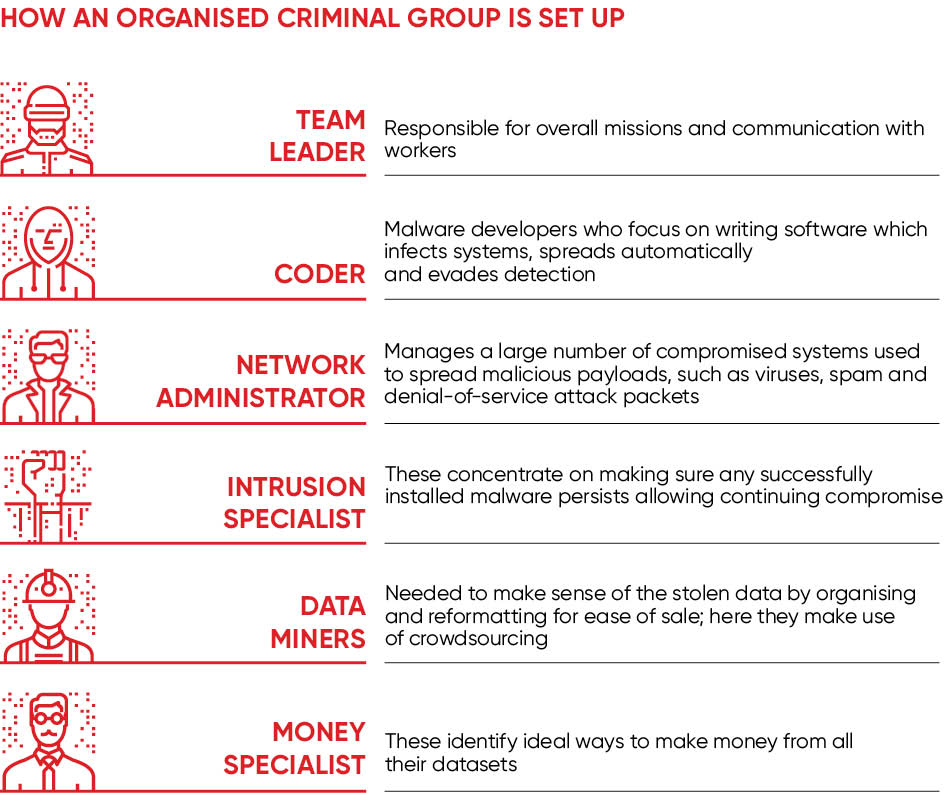

The truth is that your average cyberattacker will be part of an organisation that is far closer to a corporate enterprise in its structure. “Cybercrime units possess roles that we typically come across in any large legitimate business such as partner networks, associates, resellers and vendors,” says Kevin Curran, professor of cybersecurity at Ulster University, “and they even have dedicated call centres which are typically used to help with requests from ransomware victims.”

They even have dedicated call centres which are typically used to help with requests from ransomware victims

So who are the successful threat actors and how do these criminal groups organise themselves? The youths in hoodies certainly do exist but, as new entrants in the cybercrime fraternity, are usually “only capable of leveraging low-level hacking tools”, says Travis Farral, director of security strategy at Anomali. “But they may eventually be writing their own tools or enhancing the capabilities of existing tools,” he says.

Almost inevitably, as they mature they become part of sophisticated cybercrime groups. Interestingly though, Jim Walter who is senior research scientist at Cylance, says the more sophisticated a crime group is then the more isolated it becomes. “That’s true for government or nation state-sponsored operations and criminal groups as well as those that straddle either side. Whereas mid-tier operations have more visible partners and will use any enabling resource you can imagine,” he says.

These will include much the same open source and commercial tools that legitimate organisations rely on to do business. “Criminals will use common tools like WhatsApp, Slack and Google Groups to conduct their business in real time; tools that are available on both the regular internet and the onion-routed networks commonly referred to as the dark net,” says Chris Day, chief cybersecurity officer at Cyxtera.

But Ed Williams, senior threat intelligence consultant at Context Information Security, doesn’t believe it’s always such a dark world. “Brazilian cybercriminals, trailblazers when it comes to financial cybercrime, are renowned for communicating and marketing their wares on social media,” he says.

Cybercriminals are able to leverage automation to drive down the unit cost of launching an attack

Morgan Gerhart, vice president at Imperva, argues that cryptocurrencies and dark webs have between them added liquidity to the broader cybercrime industry, and dramatically reduced transaction costs and counterparty risk. “With those market enablers in place,” Mr Gerhart insists, “cybercriminals are able to leverage automation to drive down the unit cost of launching an attack.”

Also driving down the cost are specialisation and compartmentalisation in the cybercriminal underworld. Tim Brown, vice president of security architecture at SolarWinds MSP, says there’s a focus on “specific services and making sure that these work exactly as advertised”.

Hardik Modi, senior director of the security engineering and response team at Arbor Networks, agrees. “Each of these components are routinely upgraded and customised for use in new campaigns, pointing to dedicated and separate teams of competent programmers,” he says. Indeed, the cybercrime industry has become so robust that an attacker can hire out work for each link in the attack chain at an affordable rate. Each link remains anonymous to other threat actors in the chain, reducing their risk of being found out if one link gets busted.

Hardik Modi, senior director of the security engineering and response team at Arbor Networks, agrees. “Each of these components are routinely upgraded and customised for use in new campaigns, pointing to dedicated and separate teams of competent programmers,” he says. Indeed, the cybercrime industry has become so robust that an attacker can hire out work for each link in the attack chain at an affordable rate. Each link remains anonymous to other threat actors in the chain, reducing their risk of being found out if one link gets busted.

“One group might develop the delivery system of an attack, switching out exploits when they’re no longer viable,” explains Marina Kidron, leader of the Skybox security research lab. “Another might handle the malicious payload that infects the machine and money collection outsourced to a mule.”

And this last service might just be the Achilles’ heel of cybercrime gangs. Ian Trump, chief technology officer at Octopi Research Lab, argues that “stolen money and fraudulent purchases have to be laundered” and, no matter how sophisticated the malware might be, “making money from cybercrime requires this service layer”.

Indeed, the risk in the mule operation can be seen in the success of law enforcement across 26 countries during European Money Mule Action in November. According to Europol, in just one week a total of 766 mules were identified, 409 interviewed and 159 arrests made. Importantly, this operation also resulted in 59 mule recruiters being identified, useful information when profiling cybercrime organisations.

Law enforcement operations have also had considerable success in disrupting dark-web marketplaces of late. Earlier this year, both AlphaBay and Hansa Market were taken down, representing two of the biggest players in this underground cybercrime economy. Investigators had effectively been running the latter for at least a month and used it to collect information on criminals flocking to it after the former was shut down. Quite apart from anything else, this kind of disruption introduces an increased uncertainty of who cybercriminals can trust.