The first census of the population in England and Wales in 1801 marked a new era of data collection. It enabled those in power to understand better the distribution of people around the country, as well as track how major events affected the population’s structure. In the 219 years since the first census, data has been collected for every decade except in 1941. Before the internet, it was a vital tool in informing governments about the socio-economic and demographic status of citizens, enabling them to make better-informed decisions about resource allocation and policy strategy.

But it is not without risks. “The concept of censuses is a major catalyst for why data protection exists in the first place,” says Emily Overton, principal consultant at record manager RMGirl, citing examples of when data drawn from them has been utilised to dangerous ends, such as in Nazi Germany. “We have special categories of personal data because someone has died as a result of being on a list.”

In the past, data was collected by distributing a paper form, returned to the Office for National Statistics (ONS) by post. This continued until the 2011 census, when people were given the option to complete the form online. Some 16.4 per cent, almost four million, did. The 2021 census will be the first to be conducted primarily online, with the ONS setting a target of 75 per cent for digital submissions. In practice, this will mean most households will receive a code in the post, giving them access to an online portal.

This shift may not seem noteworthy, given the increasingly online world we live in. Nonetheless, as with the implementation of any new government process, there will be implications beyond those intended, and new considerations and concerns for those on both sides of the process.

Data privacy concerns will be a challenge

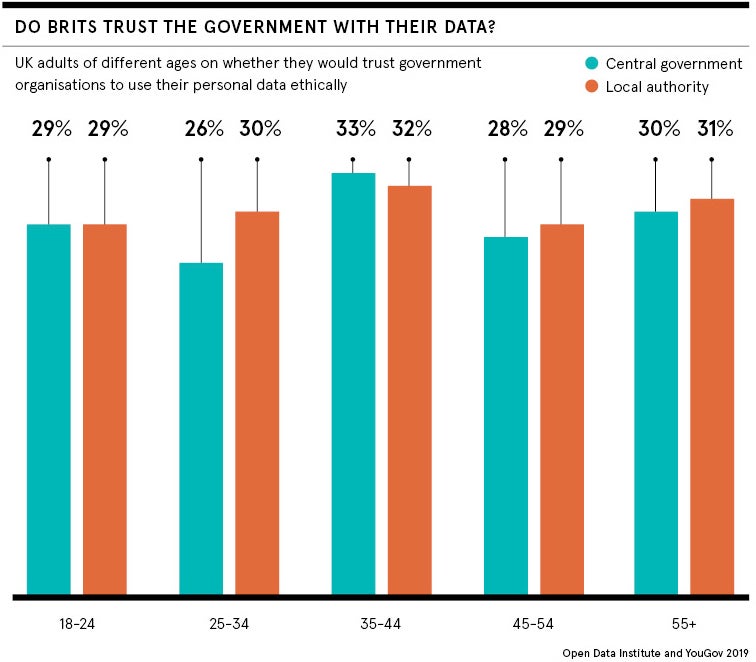

The global level of concern around data privacy has increased in recent years, in response to very public data breach scandals. At home, a 2019 survey by the Information Commissioner’s Office demonstrates that public trust in organisations and governments is slowly decreasing when it comes to data protection, with those declaring “low confidence” rising from 36 to 38 per cent since 2018.

“There’s definitely a growing nervousness on the subject of data breaches,” says Tostig Pearson, head of innovation, training, education and security at data consultancy DTSQUARED. “The biggest challenge to the implementation of the digital census is likely to be an erosion of public trust. The average person on the street is aware of GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation] and we’re all painfully aware of the government’s questionable technological competence after the Test and Trace debacle.”

This is relevant for a few reasons. Firstly, the census is compulsory for every household in England and Wales, carrying a penalty of £1,000 for those who do not comply. This is highly problematic if people don’t trust its intentions, especially given that new sensitive questions around sexuality and gender identity are expected to be included.

Can the new digital census promise anonymity?

Secondly, the concept of anonymity was easier to accept when the census was carried out by paper forms and returned in the post. “I can see a lot of people struggling to trust their data will be anonymised when it is, essentially, traceable,” says Pearson, although he is quick to add this will be much more of a perceived risk than an actual one. “The ONS are the last people in the world who want to get caught out by a data breach, so we have to assume we’ll be submitting to a belt-and-braces system.”

The concept of censuses is a major catalyst for why data protection exists in the first place

This sentiment is echoed by ONS census director Nicola Tyson-Payne, who is explicit about how important data security is to the organisation. “The safety of people’s information is our top priority,” she says. “We are constantly reviewing and renewing our procedures, and a rigorous assessment by an independent agency concluded our extensive plans to protect people’s information are robust.”

Thirdly, many people are likely to question the need for a census in 2021, when so much personal information is already held by government agencies. “The problem is that much of what is being asked of people in the census is information they already have access to, whether it’s via local authorities, HM Revenue & Customs, the Foreign Office or the DVLA [vehicle licensing],” says Pearson. “I think people will question why they are being legally forced to resubmit this information.”

And for those who don’t have internet access or would simply prefer to fill their forms out on paper? “We are aware not everyone will be able to, or will want to, do their census online and paper questionnaires will be available for those who need them. We will also have a range of support services from online help to phone support, as well as community hubs providing assistance,” says Tyson-Payne.

A shift to e-governance?

It is easy to focus on the potential negative implications of the digital census, but there are, of course, many benefits that can come from streamlining and digitalising the way a government interacts with its citizens.

“An online-first census will help improve data quality and enable census data to be processed faster and more efficiently,” says Tyson-Payne. It also indicates a further step towards a system of egovernance in the UK. For evidence of the potential benefits, you need look no further than Estonia, which has made 99 per cent of public services available online. According to Estonian government estimates, this has brought about 844 years in efficiency gains. In addition to improving access for citizens to public services, the shift to egovernance has also improved transparency.

Regardless of potential benefits, the introduction of the digital census is likely to face resistance, which will naturally lead some to question whether or not we need one at all. “Either way, there will certainly be a lot of noise,” says Pearson. “But the digital version is also the first step towards creating a more dynamic census in 2021 that is more responsive to the demands of the nation, which can only be a good thing.”

The first census of the population in England and Wales in 1801 marked a new era of data collection. It enabled those in power to understand better the distribution of people around the country, as well as track how major events affected the population’s structure. In the 219 years since the first census, data has been collected for every decade except in 1941. Before the internet, it was a vital tool in informing governments about the socio-economic and demographic status of citizens, enabling them to make better-informed decisions about resource allocation and policy strategy.

But it is not without risks. “The concept of censuses is a major catalyst for why data protection exists in the first place,” says Emily Overton, principal consultant at record manager RMGirl, citing examples of when data drawn from them has been utilised to dangerous ends, such as in Nazi Germany. “We have special categories of personal data because someone has died as a result of being on a list.”