Donald Trump made clear his priorities in his first formal address after being inaugurated president when he chose the media as his target and denounced it for containing “among the most dishonest human beings on Earth”.

Mr Trump has abandoned Washington protocols allowing journalists access to his events. During the election campaign he described the press as “disgusting”. After his victory, he branded the BuzzFeed website as a “failing pile of garbage” and the CNN network as “fake news”. He has reportedly been stopping White House officials from appearing on that news channel.

For politicians to have fraught relations with the media is nothing new; press censorship remains a scourge from Turkey to North Korea. But Mr Trump’s stance as leader of a nation that cherishes free speech in the first amendment of its constitution represents an unprecedented break with the longstanding relationship between media and politics in America, or at least the mainstream media.

Although he brought Rupert Murdoch into Trump Tower last month and gave The Times an interview, the president is primarily seeking to sidestep traditional channels of addressing the electorate by establishing his own media platforms, most obviously his @realDonaldTrump Twitter account on which he issues polemical observations on policy to an audience of 24 million followers.

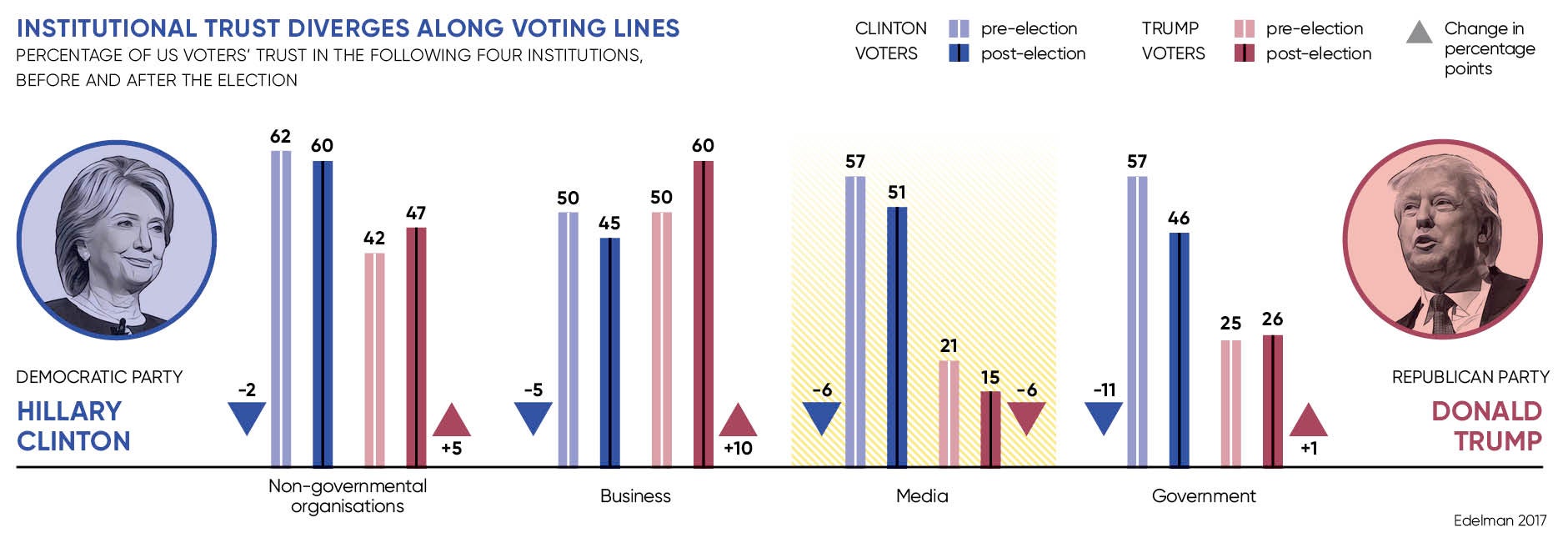

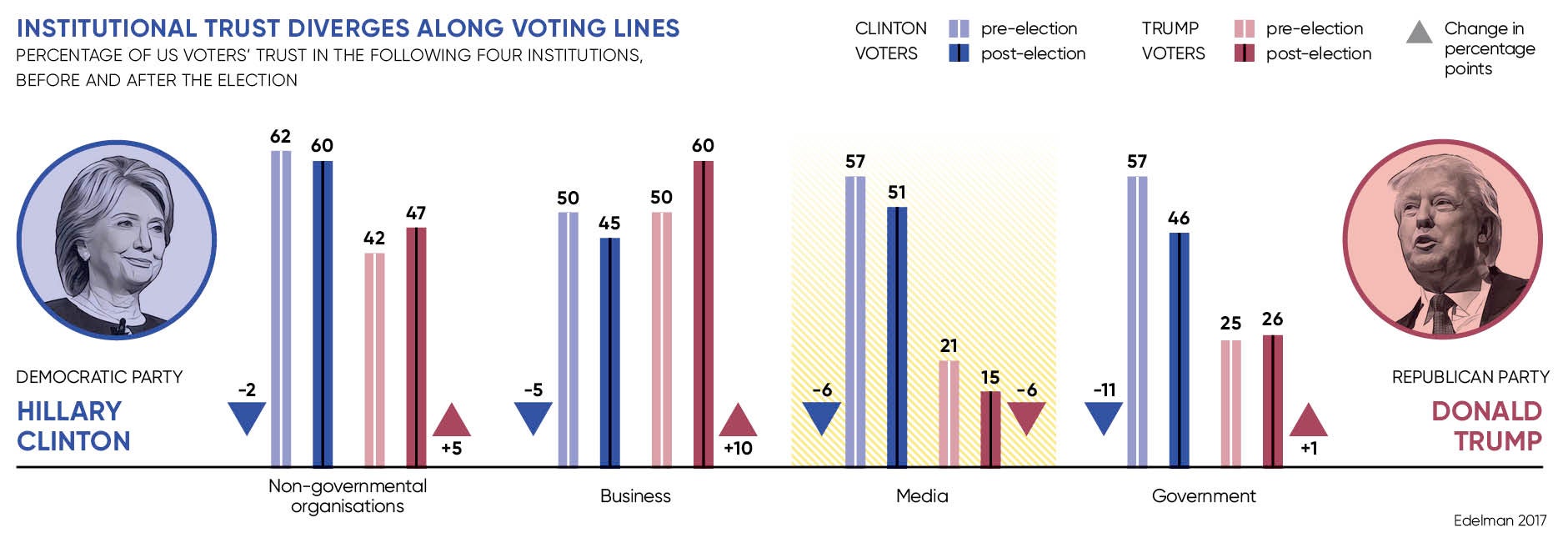

At the same time he encourages the rise of alternative media which supports his agenda, most notably the hard-right website Breitbart News, whose executive chairman Steve Bannon has been hired by Mr Trump as chief strategist. The president knows his tactics have a greater chance of success if the public’s belief in mainstream news can be undermined by his attacks on its integrity. It seems to be working. The Edelman Trust Barometer 2017, released last month, showed falling levels of faith in traditional media, down from 48 per cent to 43 per cent in a year.

Across the world, populist politicians are looking at Mr Trump’s media strategy as a model for mobilising their own support

Into this increasingly murky and disputed picture has come the scandal of “fake news”; the practice of disseminating authentically packaged but false information in the expectation that it will be virally shared online. In some cases this misinformation is being sanctioned at the dark extremes of international politics, as social media offers new opportunities for spreading propaganda. US Director of National Intelligence James Clapper claimed Russia was behind fake stories intended to sway the outcome of the US election.

These circumstances have created a lack of faith among large sections of the public in the media’s ability to properly report on politics, a phenomenon not confined to America.

Fake news in the UK

Sky News presenter Sophy Ridge, host of political show Sophy Ridge on Sunday, says Brexit has undermined media trust in the UK. “I think there has been a frustration in certain parts of the country that there is a Westminster bubble and journalists are part of it,” she says. “Most journalists work in London, live in London and talk to people in London, which is probably why, for some journalists, what happened last year in the UK with Brexit did come as a bit of a surprise.”

She makes an effort to “break out” of central London and speak to voters across the UK and to MPs in their constituencies, saying it is important that elected representatives engage with the news media. “I think there perhaps is a danger – and you see it with Donald Trump – that politicians want to use their own media channels, through Twitter and Facebook. I do think that is slightly dangerous because it means there are no checks and balances on what people say.”

Across the world, populist politicians are looking at Mr Trump’s media strategy as a model for mobilising their own support.

And so a complex and interdependent relationship, in which the media was part-watchdog and part-mouthpiece for the political classes, has become increasingly adversarial.

Nic Newman, a former BBC journalist and the author of the recent Oxford University Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism report, Journalism, Media and Technology Predictions 2017, talks of a new “polarisation” of news, which is damaging mainstream professional journalism and its reputation for impartiality.

A big part of it is engaging audiences with fact-checking and verification rather than just pushing information to them

Acute sensitivities to bias that once only applied to the most sensitive subjects, such as the Israel-Palestine question, are present across the news agenda, from the environment to human rights. The middle ground of accepted facts, which journalists could analyse and investigate, has evaporated. Accusations of media distortion come from all angles. “When you get much more polarised issues, then the media finds it really difficult and generally gets attacked from both sides,” says Mr Newman.

And yet his report also reveals that news publishers see the rise of fake news as an opportunity, with 70 per cent of respondents saying it would strengthen the position of news media, compared with 17 per cent who believed it would have a weakening effect.

Fact-checking

If the news media is to regain public trust, it will need to show greater transparency in its sourcing, as Reuters editor-in-chief Stephen J. Adler says: “It’s a time to double down on being unbiased, and being careful and being dispassionate good journalists.”

The other area where the media can prevail over the fog of fake news is in verification. The British- based website Bellingcat has had success against the odds in exposing Kremlin-backed propaganda, notably around the downing in 2014 of the MH17 airliner by a Russian Buk missile in Ukraine. Eliot Higgins, the website’s founder, says the wider news industry must do more. “We are a tiny organisation doing quite a lot of lifting work in this area, and there needs to be quite a lot of support from other organisations and more of a strategy,” he says.

There are important initiatives such as the First Draft project, which includes The New York Times and broadcaster Al Jazeera among its partner organisations, sharing best practice in verifying online stories. The Washington Post launched a tool that promptly checks Mr Trump’s tweets. And Le Monde and Libération have invested in fact-checking services ahead of the French election.

But Mr Higgins says the news industry must bring the public on board. “A big part of it is engaging audiences with fact-checking and verification rather than just pushing information to them, saying ‘This is fake, this is false’,” he says. “In an era of smartphones and more interactive technology I think people expect to be engaged.”

MP Tom Watson, deputy leader of the Labour Party, was at the forefront of attempts to clean up the news media following the phone-hacking scandal that led to the closure of the News of the World in 2011. He argues that the deliberate concoction of false news has become a critical issue for both politicians and the media.

“Politicians get frustrated when we see journalists spin information, but we generally defend their right to do so. Fabricating information is a different matter. None of us can make informed decisions based on fake facts,” he says.

As for a breakdown between politicians and the media, Mr Watson warns colleagues against trying to stand apart from the traditional news industry. “We have always had a strong, robust and fiercely independent media in this country, and any politician who believes they can bypass it by using social media will quickly discover they aren’t being heard,” he cautions.