The River Humber and its access to the North Sea helped to make Hull and the surrounding area one of the most prosperous in England during the Middle Ages. Now businesses and politicians are looking to green energy investment on both banks of their “Energy Estuary” to drive the region’s renaissance.

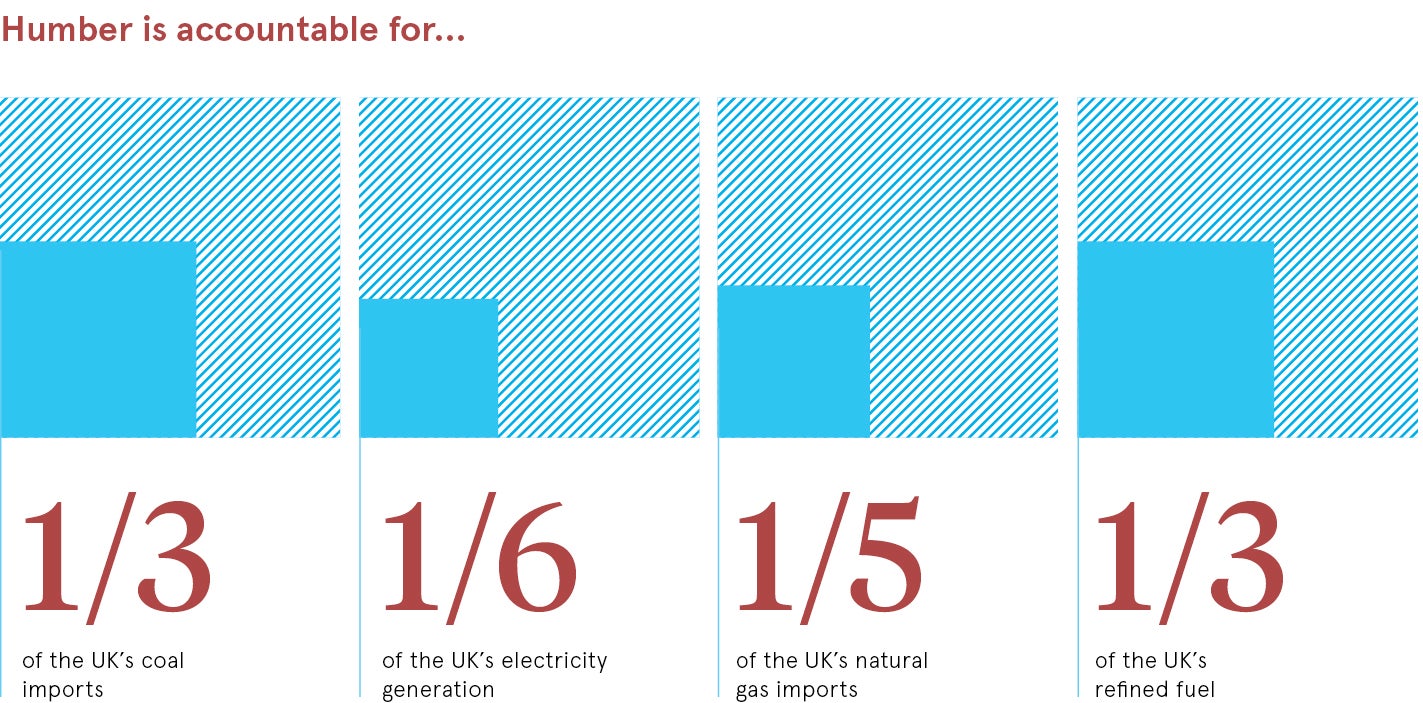

The area has long been a centre for energy production, storage and handling. It is home to two of the UK’s six main oil refineries and is estimated to import one third of the nation’s coal, one fifth of its natural gas and produce almost a fifth of its electricity.

Now the Humber region is seizing opportunities created by the wind industry taking shape off its coast, where six wind farms are already operating, another is under construction and three more are planned. Ørsted, the largest operator, formerly known as Dong Energy, will have invested £6 billion there by 2019.

Siemens Gamesa injecting £310 million into offshore wind power

In Hull, Siemens Gamesa and Associated British Ports (ABP) have invested £310 million jointly to make turbine blades for offshore wind. It began operating 18 months ago as the centrepiece of the Green Port Hull project at the city’s Alexandra Dock.

Grimsby, which like Hull has fought industrial decline since its fishing industry shrank, is establishing itself as an operations and maintenance centre for offshore wind.

“We’re just at the beginning of the journey. There have been a lot of obstacles to overcome,” says Tim Rix, who chairs the Green Port Growth Programme, created with £25.7 million from the government’s Regional Growth Fund to maximise the economic impact of the Siemens-ABP investment.

Siemens Gamesa has invested in a factory at Alexandra dock to make turbine blades for offshore wind farms

Setbacks on the road to greener energy

Other green initiatives include Hull-based Spencer Group’s £200-million Energy Works scheme, which is a power-from-waste plant combined with a renewable energy research facility. On the south bank, a £170-million waste-to-energy plant is proposed for Immingham by developer North Beck Energy.

There have been setbacks. Vivergo, the UK’s largest bioethanol producer, based at Saltend Chemicals Park near Hull, recently suspended production for four months because it said the government had broken promises on policies to boost the use of biofuels for transport.

The energy sector employs 17,000 people in the region, accounting for 5.1 per cent of employment

Siemens took three years to commit to its Hull investment. The Humber, like many parts of the north of England, was hit hard by the 2008 financial crash and following recession. The area’s push into green energy has since regained momentum and the priority now is to extend the benefits in terms of contracts for local suppliers and jobs, as well as attracting new investors.

The energy sector employs 17,000 people in the region, accounting for 5.1 per cent of employment, according to the Humber Local Enterprise Partnership. That is smaller than, for example, the health and social care sector or the food industry, but it also helps to boost the engineering, manufacturing and logistics sectors.

Creating jobs in the energy sector and beyond

A study by the University of Hull found that the Siemens Gamesa plant had created 1,000 jobs directly and supported the creation of more than 1,000 indirectly.

“We have tried to use local suppliers wherever possible,” says Andy Sykes, an operations manager at the factory, pointing to wooden platforms made by Hull’s Turner Timber. Tool manufacturers, fabricators and industrial cleaning companies are others that have benefited.

Mr Sykes says Siemens has succeeded in finding the skills it needs. “We have had more than 28,000 applicants for the roles here. It’s certainly captured the imagination of the region – 98 per cent of all the people employed here are from within 30 miles of the factory,” he says.

Hull College has created a centre specialising in manufacturing skills and composite materials to train the Siemens workforce. Siemens staff have undergone two-week courses at its facilities, including a turbine blade school that replicates, in miniature, all the processes within the factory.

Providing opportunities to small, local businesses

Getting more small local companies geared up to supply the likes of Siemens and Ørsted is still work in progress, however. “This is something that is going to take a lot of years. It is difficult to establish yourself as a supplier to these large companies,” says Mr Rix, who as well as his role with the Green Port Growth Programme chairs J.R. Rix & Sons.

He is the fifth generation to work in the family business that started as shipowners in the 1870s. Its main businesses now include fuel distribution and static caravan manufacturing, but five years ago it closed its dry cargo operation and replaced it with a business supplying crew transfer vessels to offshore wind farms.

The company has six boats, four of them working out of Grimsby. However, Mr Rix concedes: “It has been a challenge. Having struggled for the last three or four years, we have now suddenly started to get business on our front doorstep. I think the business will stabilise and there will be significant opportunities.”

The Humber: an engine for economic benefit

The Energy Estuary strategy involves the region’s four local authorities alongside businesses and ABP, which operates the ports of Hull, Goole, Immingham and Grimsby. All parts of the region have worked more closely together than has sometimes been the case in the past.

Apart from its £150-million Green Port Hull investment, ABP has spent £140 million on a terminal at Immingham to supply biomass to Drax power station. Drax has spent the past few years converting half of its six generating units to burn wood pellets instead of coal, with a fourth to follow this year.

The Humber is a massive engine for economic benefit for the North and also the whole of the UK

“In the time we have seen coal diminish, we have seen other energy-related areas pick up,” says Simon Bird, ABP’s director for the Humber ports. “My role is to work with all the major players in the energy sector and make sure we have the right facilities to enable them to expand. I’m very confident we have that across the four ports.”

He describes the Humber, the UK’s busiest port complex, as “a massive engine for economic benefit for the North and also the whole of the UK”. Not only does it face northern Europe, it also has a strategic position at the centre of the UK, equidistant between London and Edinburgh.

Mr Bird says: “The Humber is a major player in energy, but also in a number of other sectors. All those sectors need to co-exist and they all require water.” The volume of container traffic at its terminals in Hull and Immingham has increased by 28 per cent over the past year, he adds.

How the Energy Estuary is raising the region’s profile

Alan Menzies, director of planning and regeneration at East Riding Council, says the Energy Estuary initiative is important as “one key strand of an economic strategy, making use of natural assets and skillsets which exist locally”. But it must work alongside his council’s other strands, such as tourism and developing the M62-A63 corridor between Goole and Hull.

The East Riding, the area surrounding Hull, has one of the UK’s main gas terminals at Easington, an underground gas storage facility at Aldbrough and about 20 onshore wind farms. A £200-million energy and technology park, which could create more than 1,000 jobs, has been proposed on the outskirts of Hull.

Mr Menzies believes the Energy Estuary initiative helps to raise the region’s profile. To reap the benefits, he adds: “There’s more work to be done on suppliers, small and medium-sized enterprises, because there are elements of supply which are not local. There is also work to do in terms of getting to the right level of educational attainment.”

The £10-million Ron Dearing University Technical College in Hull, developed with funding from local businesses, opened its doors last autumn. It aims to equip students aged 14 to 19 with advanced digital and engineering skills.

“Unless we have the infrastructure in place, people will go elsewhere,” Mr Rix concludes. “You’ve got to look at what industry is likely to require and how that can be delivered.”

Case Study: Regeneration through renewables

Grimsby had one of the world’s largest fishing fleets at its peak in the 1950s. New jobs in operations and maintenance for offshore wind farms are helping in its long battle to fill the gap that fishing’s decline has left.

Ørsted, the largest operator of wind farms off the coast, employs about 200 people in Grimsby docks, which is expected to grow to 500. Centrica, Siemens and E.ON also have hubs there.

“Renewables is a big opportunity for us, but I don’t think we have experienced the level we initially expected in terms of employment,” says Angela Blake, director of economy and growth at North East Lincolnshire Council. “It is growing and it’s got potential, but I don’t see it being as big as food processing.”

Despite the demise of its fishing fleet, Grimsby accounts for more than 70 per cent of all seafood processed in the UK, employing 5,000 people.

The offshore wind jobs being created are predominantly in mechanical and electrical engineering. In its recruitment campaign for wind turbine technicians, Ørsted says candidates should be physically fit, have an aptitude for working at heights and in restricted or confined spaces, and be comfortable working offshore or in vessels for extended periods of time.

Siemens Gamesa injecting £310 million into offshore wind power