When it comes to reputation, a company is only as good as its supply chain. Responsibility begins long before the checkout or factory floor and earlier, even, than the quarry lorry or farm gate.

Managing supply-chain risk, though, remains a challenge, says Duncan Brock, director of customer relationships at the Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply (CIPS). “Modern supply chains are often very complex and assessing all the potential ethical and environmental implications can be extremely difficult,” he says. “The best way is to conduct a full risk analysis upfront to determine where effort should be targeted.”

Strategic supply-chain mapping can identify priorities. However, research by Action Sustainability for the Supply Chain Sustainability School has highlighted just how complex a supply-chain map can get. Their study looked at a basic staple of health-and-safety procurement, the hi-vis vest.

Mapping its production revealed no fewer than six different countries involved – India, China, United States, Germany, Morocco and UK – with multiple journeys between them. Navigating this supplier maze means understanding what happens where, says Dr James Cadman, lead consultant with Action Sustainability. “Supply-chain mapping is a useful tool to help you prioritise your actions and decisions on supply-chain risk,” he says. “It is not the answer, but it is part of the solution.”

Even auditing from top to bottom is not enough, adds Mr Brock. “Businesses also need to be wary of developments in the wider world. The CIPS Risk Index is close to its all-time high, largely due to widespread political uncertainty and protectionism,” he says.

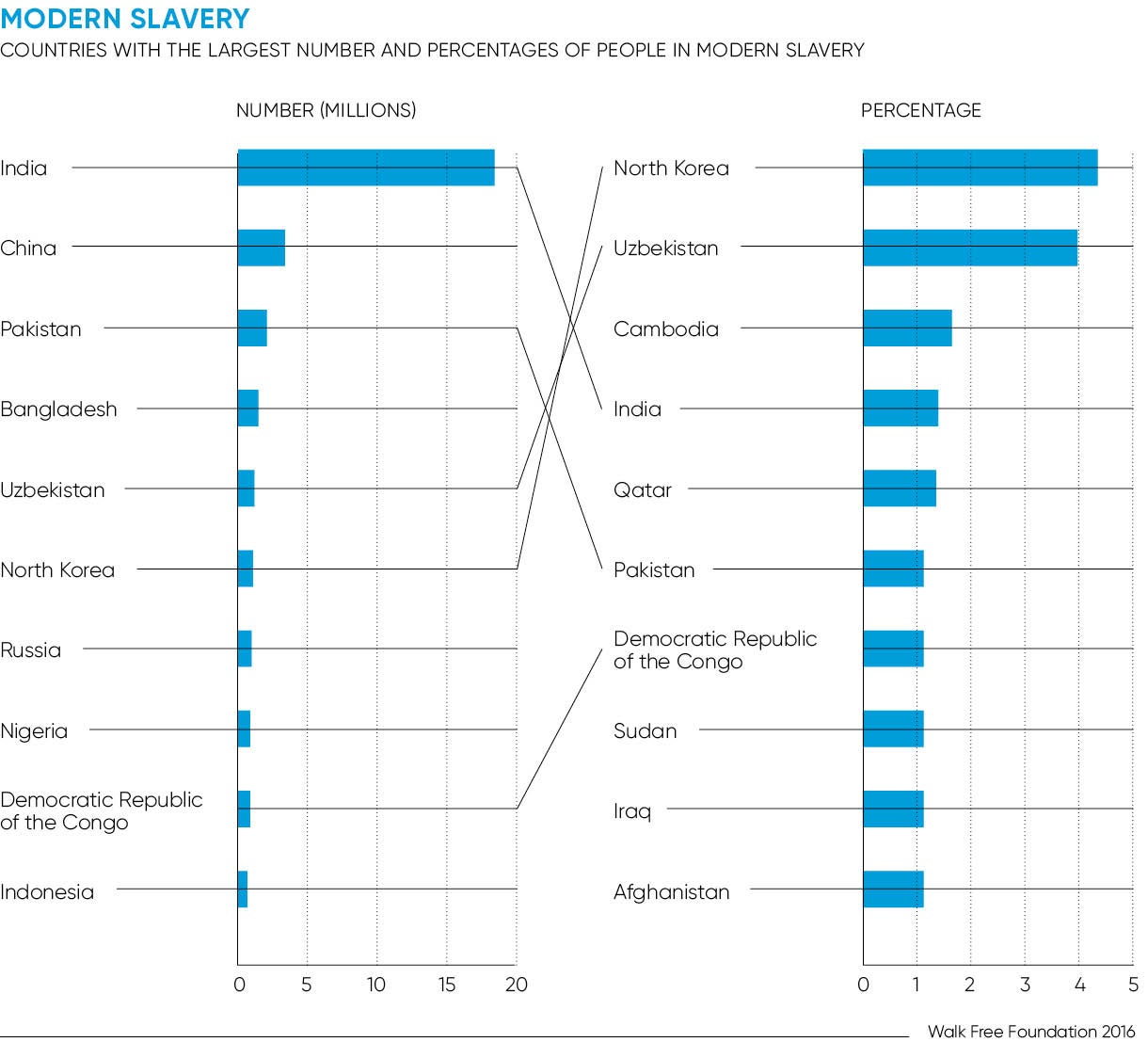

Extending the remit to factor in events and externalities beyond direct impacts takes business into the arena of human rights. As well as forced and child labour, this might mean looking at wider community and societal issues, such as water abstraction in drought areas, polluting emissions in countries with weak regulation, bribery and corruption, or even trade indirectly funding conflict or terrorism.

International companies and global brands have begun producing standalone human rights reports to account for broader responsibilities and demonstrate transparency

In response, international companies and global brands have begun producing standalone human rights reports to account for broader responsibilities and demonstrate transparency.

One such organisation, along with ABN Amro, Coca-Cola and Unilever, is Marks & Spencer. As well as being a matter of principle, this focus also serves a practical purpose, explains corporate head of human rights at M&S, Louise Nicholls. “There is no place for modern slavery or any human-rights abuse in any business. That’s why we’ve taken action to prevent it across our supply base. Training suppliers to spot often hidden signs and giving them tools to train their suppliers builds resilience into their business and, in turn, your business,” she says.

Marks & Spencer, which published its inaugural Human Rights Report in 2016, outlines the steps the retailer is taking to support and respect human rights

In some respects, global scrutiny around human rights appears on the up, with expectations increasing on business.

Special rapporteur on human rights defenders (HRDs), Michel Forst, recently reported to the United Nations general assembly that the “responsibility of businesses to respect human rights not only entails a negative duty to refrain from violating the rights of others, but also a positive obligation to support a safe and enabling environment for HRDs”.

The shocking number of attacks on HRDs is also rising, though. Global Witness reports killings of defenders not only growing, but spreading. In 2016, it documented 200 killings across 24 countries, compared with 185 across 16 in 2015.

Companies and industries are in the spotlight. In the last 30 months, the Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (BHRRC) has tracked more than 770 incidents of attacks and harassment against people raising concerns around business activities. Their public database reveals 75 per cent of cases relate to land-intensive industries, such as extractives and agriculture, but also wind-turbine and dam-building renewable-energy projects. Latin America is highest risk, with Colombia, Brazil, Mexico, Honduras and Peru accounting for more than half of cases logged.

In defending HRDs, advocacy is vital, but so too is back-up on the ground. Front Line Defenders works to provide practical support, including emergency assistance, protection and security guidance to individual HRDs, alongside international advocacy. One of their active cases is Rodrigo Mundaca, at risk in Chile. Featured in Amnesty International campaign Brave, he is an agricultural engineer and spokesperson for MODATIMA.

MODATIMA works to promote water rights in Petorca, where local community access has deteriorated dramatically. Shortages caused by droughts have been exacerbated by huge increases in water-intensive production of avocados, also resulting in widespread privatisation and emergence of illegal pipes.

Mr Mundaca and members of MODATIMA have faced death threats, criminal charges and harassment. They have been threatened with violence and imprisonment and targeted with defamation campaigns.

Isolating activists can be part of a recognisable pattern of attack, explains Erin Kilbride of Front Line Defenders. “In the vast majority of cases, HRD killings were preceded by warnings, death threats and intimidation which, when reported to police, were routinely ignored,” she says. “Often, even before threats begin, defenders are subjected to smear campaigns and defamation, labelling them ‘anti-development’ or ‘eco-terrorists’, to strip away the activists’ networks of support.”

Such attempts to shrink the ability of civil society to raise concerns are increasing in the Western world and the negative effect on supply-chain visibility is not just detrimental to transparency, but also bad for business intelligence, concludes Ana Zbona, human rights defenders project manager at BHRRC. “Crackdowns on civic freedoms threaten companies’ access to information about what is really going on in their supply chains. Businesses should recognise and acknowledge the importance of these critics in the process of human-rights due diligence,” she says.

From product miles in a hi-vis vest to violence in the humble avocado of your guacamole, supply-chain stories can be complex, even criminal. The responsibility involved carries risk, but also brings reward. Either way, companies are now in the business of human rights.