By 2020 more than ten million people are expected to be new savers or saving more as a result of pension auto-enrolment reforms, according to the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). All firms, in a gradual rollout since 2012, must provide a pension for their staff and even an employer of a nanny must auto-enrol them in a scheme.

So far, more than seven million people have already been auto-enroled into a workplace pension by more than 250,000 employers.

Auto-enrolment applies to workers aged at least 22, but under state pension age, usually working in the UK and earning more than £10,000 a year unless they are already a member of a pension scheme that meets certain criteria set out in law. A worker who is auto-enroled into a scheme has the option to opt out of it within one month if they choose.

At the moment, employers and employees must each contribute 1 per cent of an employee’s qualifying earnings until April 2018 when employer minimum contribution rates will rise to 2 per cent with employees contributing 3 per cent. By April 2019, employers must pay a minimum of 3 per cent of qualifying earnings per employee into a pension scheme with employees contributing 4 per cent with the government adding 1 per cent tax relief. Employers need to repeat the auto-enrolment process approximately every three years.

Why it’s not enough

Most industry experts say contributions are far too low. To replicate fully the kind of pension which would have been enjoyed by someone with decent service in a final salary scheme, today’s new worker, according to the Royal London policy paper The Death of Retirement, would need to work until they were 77 based on contributions at the statutory minimum. Even disregarding the valuable benefits of inflation-protection and provision for spouses, the worker would need to work until 73.

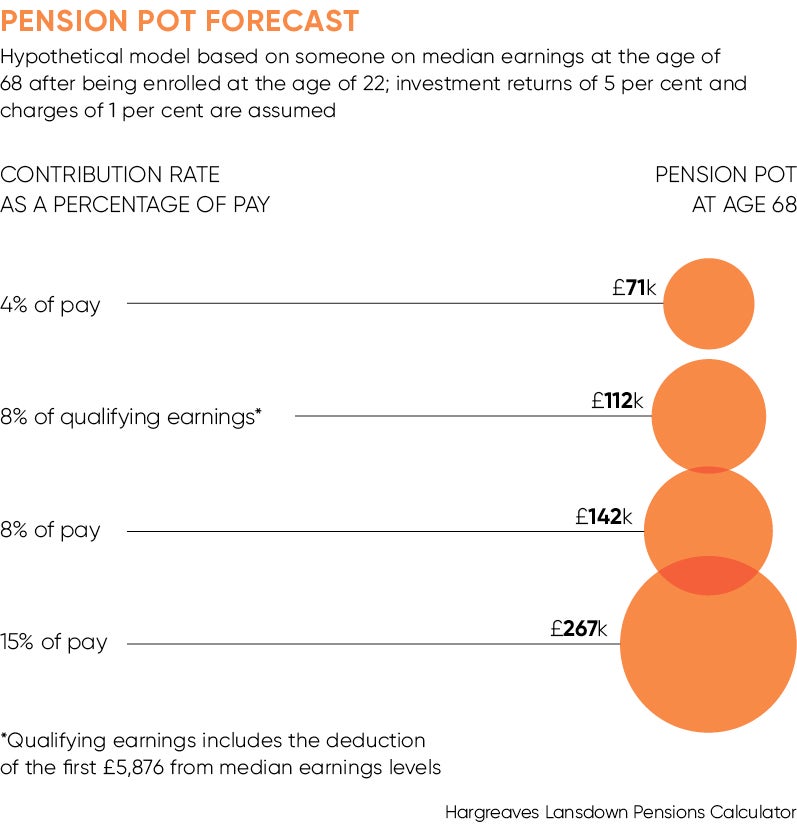

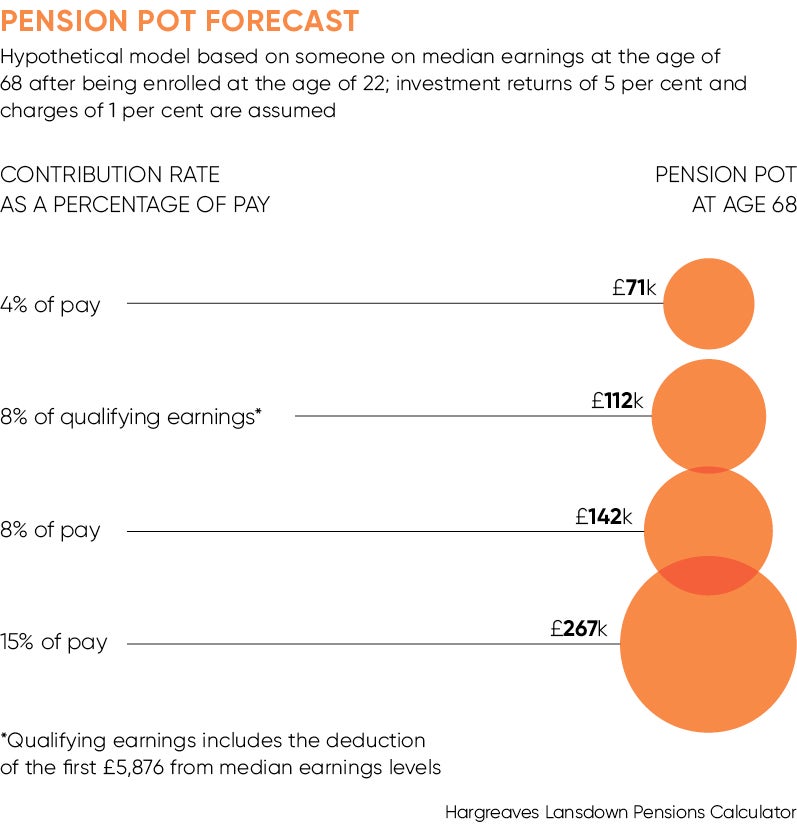

Richard Butcher at PTL agrees: “The 8 per cent contribution is too low to provide most people with enough money to be able to provide, along with the state pension, an adequate income in retirement. Modelling by the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association suggests contributions should increase to around 12 per cent.”

David Weeks, co-chair at the Association of Member Nominated Trustees, goes further. “I would like to see a target of 15 per cent of qualifying earnings,” he says.

However, there is a danger that if contributions are too high, people will opt out. Research from NOW: Pensions shows that 24 per cent of auto-enroled savers say they “definitely will” or “might” opt out, when minimum contributions hit 8 per cent of qualifying earnings in 2019.

This is a fraction of the amount needed for a decent retirement

To counter this, Bob Scott, chairman of the Association of Consulting Actuaries, would like to see more flexibility so, as minimum employee contributions increase, for example from 3 to 4 per cent, employees are given the option to elect to go back down to 3 per cent before being able to opt out.

“For employers and employees staging late in the process, there should be a phasing in of minimum contributions, not an immediate jump to 8 per cent,” he says. “The same goes for new businesses. A phasing in of minimum contributions for younger employees also seems sensible.”

Another important factor is qualifying earnings. Workers’ contributions are limited as they can only make contributions based on their qualifying earnings. This means the first £5,876 of earnings, as well as anything they earn more than £45,000, are not used to calculate their pension contributions.

This has an important impact on their ultimate pension. Sir Steve Webb, former pensions minister and now director of policy at Royal London, explains: “If someone is using qualifying earnings, they could end up only contributing around 6 per cent of pay for the typical automatically enroled worker. This is a fraction of the amount needed for a decent retirement.”

Other urgent reforms needed

Tim Gosling, the Pensions and Lifetime Savings Association defined contribution policy lead, says: “The government should look at bringing in younger people aged between 18 and 22, the self-employed and those with total earnings over £10,000 from more than one job.” Mr Butcher agrees: “There are no sensible pension arguments against any of this.”

Ferdinand Lovett, senior associate at law firm Sackers, points to changing working patterns. The whole auto-enrolment process hangs on who is a “worker”. He says: “Employment status is becoming much more ambiguous. The recent Uber and CitySprint tribunal cases have shown this, and this needs immediate attention.”

Phil Farrell, partner at Quantum Advisory, urges simplification of the process. “Current legislation is far too complex and onerous, especially for smaller sized employers who may be unable to afford the cost of obtaining professional advice. The Pensions Regulator’s guidance totals 11 separate documents,” he says.

At Royal London Sir Steve forecasts: “In terms of the market, I suspect the main short-term change will be the weeding out of smaller, more poorly capitalised master trusts.”

Mr Butcher agrees: “The number of master trusts will consolidate. Their economic model doesn’t work if there are too many in the market. They can’t all deliver economy of scale and make enough money to operate.”

One key change experts would like to see is a new duty on employers to review their provider, perhaps on a three-yearly cyclPhil Farrell, partner at Quantum Advisorye to coincide with re-enrolment. The risk is that employers settle for the first provider they chose simply because of the hassle of changing, but this may be to the detriment of scheme members.

Why it's not enough