If the sheer weight of reports involved was a measure of progress, the “black ceiling”, which prevents ethnic-minority talent from rising to the top, would long ago have been consigned to the history books, along with racism and gender discrimination as a whole.

Despite separate studies from the government, the Chartered Management Institute (CMI) and the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development (CIPD) in the past 12 months alone, the British boardroom upholds a deafening silence on race.

Although gender is grabbing most of the diversity headlines currently, race is on the starting blocks for 2018

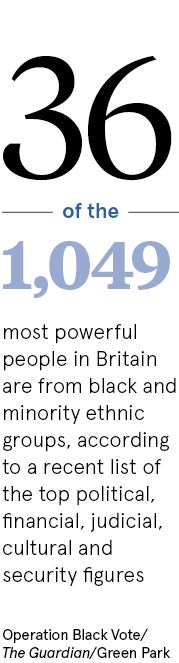

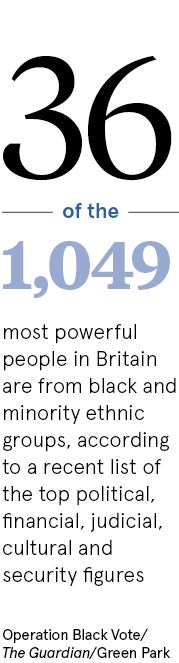

Just 6 per cent of UK managers are from black and minority ethnic backgrounds (BAME) despite accounting for more than double that in terms of the country’s workforce as a whole.

Just 6 per cent of UK managers are from black and minority ethnic backgrounds (BAME) despite accounting for more than double that in terms of the country’s workforce as a whole.

Worse still, says the CIPD, as many as 29 per cent of black employees believe racial prejudice and discrimination in the workplace has played a part in stalling their careers, echoing a 2015 Business in the Community (BITC) study, which concluded that “racism very much remains a persistent, if not routine and systematic, feature of work life in Britain”.

Progress made with gender not mirrored with racial prejudice

Yet while many organisations appear unmoved by the preponderance of so-called “snowy-white peaks” across UK industry, other protected characteristics have proved more appealing than preventing racial discrimination in the workplace.

Published last summer, the CMI’s Delivering Diversity report found that while 75 per cent of FTSE100 companies set progression targets for gender, only 21 per cent do the same with BAME.

“I can remember a time when sexual orientation was a real no-no subject in corporate circles, but like unequal pay between men and women, it has recently become mainstream,” says Sandra Kerr, race equality director at BITC.

“Although gender is grabbing most of the diversity headlines currently though, I have no doubt that race is on the starting blocks for 2018.”

Ultimately, she believes, it all comes down to money. Or to be more precise, the £24 billion which could, says the government-backed McGregor-Smith Review published last year, be added to the UK economy if career opportunities between ethnicities were made equal.

“Racial discrimination at work has been a problem for a very long time, but the severe financial penalties involved in perpetuating it, particularly post-Brexit, are now crystal clear,” says Ms Kerr.

Racism in the workplace driving talent overseas

While it is likely that overt or subtle racism has already prompted many gifted BAME individuals to seek a welcome overseas, it’s the creation of a sustainable talent pipeline for the future, rather than a talent drain today, which concerns Raphael Mokades.

Founder and managing director of recruitment firm Rare, 95 per cent of whose candidates come from ethnic-minority backgrounds, Mr Mokades believes the higher churn rates among black and Asian staff continue to be overlooked.

“Although unequal pay and career opportunities are obvious causes of dissatisfaction, more subtle problems, such as feeling isolated or misunderstood, can be even more powerful,” he argues.

“One day, we may get to the stage where black lawyers quit prestigious law firms because they don’t have a work-life balance or black civil servants leave because they can’t stand the government – the very reasons why many white people quit.

“But as long as the problem is your organisation’s underlying culture, you can’t kid yourself that you’ve even got past first base.”

With BITC due to update its Race at Work report this summer, Ms Kerr notes that two of the biggest obstacles to preventing racial discrimination in the workplace which were identified three years ago – lack of data and reluctance to talk about colour – continue to make their mark.

Although mandatory reporting of the race pay gap is, she says, a crucial first step in formulating an action plan on diversity, it’s the second – the legendary British reserve – which is more problematic.

“Our 2015 work showed that some 58 per cent of white employers don’t feel comfortable talking about race in case they inadvertently offend people or get yelled at,” says Ms Kerr.

“My message to employers is that members of the BAME community don’t really care what terminology you use, just as long as you are genuinely trying to tackle these problems.”

Implication of Brexit for BAME talent

With uncertainty over Brexit already propelling talent retention to pole position in many organisations, Ms Kerr believes 2018 could be a tipping point.

“I wouldn’t disagree that we’ve already lost good people from the UK because they have grown tired of all the obstacles thrown in their way, but I firmly believe we should look to the future.”

“With one in four primary schoolchildren in this country now coming from a BAME background, there is everything to play for in terms of harnessing the talents of the next generation.”

Mandatory gender pay gap reporting, together with a tide of sexual harassment accusations, have ensured that the status of women will remain in the spotlight for the time being.

Yet in the view of Patrick Woodman, who co-authored the CMI’s Delivering Diversity report, this can only oil of the wheels of the next big diversity conversation.

“By learning what they can from the progress of the gender debate, it should be possible for organisations to make far quicker progress when it comes to tackling the complex issues regarding race,” he says.

“Having only recently grappled with sexism, I believe employers are far savvier about the entire diversity landscape than they were even a few years ago.”

His advice to employers is pithy: “Get to know your numbers intimately, set achievable targets on pay and progression across all employee groups, and remember that not being transparent on diversity is no longer an option.”

Can reverse mentoring prevent racism in the workplace?

While Mr Woodman believes short-term, long-term, next-level and “boomerang” or reverse-mentoring have a vital role to play in preventing racial discrimination in the workplace, he rejects the view that mentors and mentees should look alike.

“If we want real change for women, we need men to stand up and be counted and in my book, exactly the same rule applies when it comes to race,” he says.

BITC’s Ms Kerr agrees. “We particularly support the issue of reverse-mentoring, where business leaders meet with and benefit from more junior BAME staff,” she says.

“When a white director, say, gets to know not just one, but a whole list of BAME employees, who are bright and ambitious, but who, unlike their white colleagues, are stuck with no clear progression lines, a light is finally switched on.”