It takes two sexes to make a baby, so why when we talk about infertility is the conversation always focused on the female?

In a clinical context, a culture of blame is perpetuated by gendered language centring on “geriatric” mothers, “inhospitable” wombs or “incompetent” cervixes.

Men account for half of the fertility equation – exactly the same number of cases as attributed to women – so as ever-increasing numbers of us engage in fertility treatment, there is an urgent need to reshape medical terminology, which can leave patients, who are already in a delicate emotional state, feeling absolutely crushed.

“We have to remember that until recently infertility wasn’t something that people ever discussed openly,” explains leading gynaecologist and fertility expert Dr Larisa Corda. “The whole subject has been steeped in stigma and taboo for generations, and this continues to plague the topic.”

This gendered language is such a problem, she adds, because there is something so personal in admitting that you’re struggling to get pregnant. “It makes you vulnerable in a place that threatens your very sense of identity as a woman,” she says.

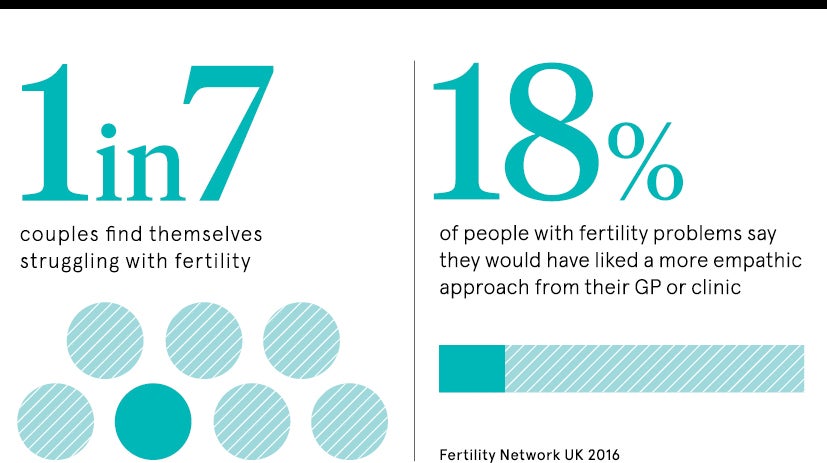

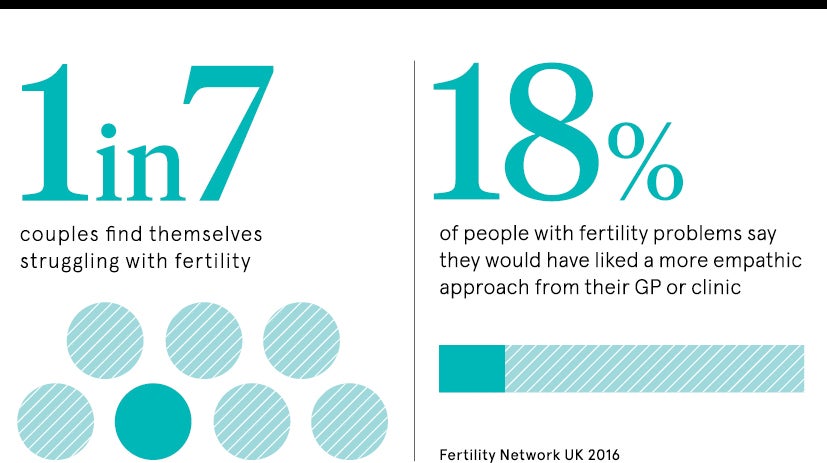

Corda points to the fact that roughly one in seven couples will find themselves struggling on their fertility journey, a figure which is only set to rise as “we continue to evolve past the point where our biological clocks are able to keep up”.

Fertility treatment for men and women

The inability to conceive naturally is most commonly a result of specific medical conditions. However, since infertility stigma is so common, it’s not openly discussed and those affected can feel completely beaten down by gendered language that seems to apportion blame. This makes women, in particular, feel evermore lonely and isolated, ashamed of their body, which is said to be “failing” them, and ultimately despairing of ever having children.

This is another reason why gendered language should change, according to the clinical psychologist Dr Janina Scarlet, author of Super-Women: Superhero Therapy for Women Battling Depression, Anxiety and Trauma.

“Having a child is many people’s ambition and life dream. For those who struggle to get pregnant, infertility can sometimes lead to trauma-like reactions,” she says. “In my professional work, I have seen many clients who were experiencing symptoms of depression and, in some cases, post-traumatic stress disorder after several attempts in which they were unable to get pregnant.”

Even some of the most basic terms, especially “failed pregnancy” when a woman suffers a miscarriage, should be eradicated from the medical lexicon, along with all those phrases that attribute blame to specific female body parts.

“It is time to spread awareness regarding infertility and help both doctors and non-doctors alike to understand the harmful implications of such insensitive language,” says Scarlet. She adds that often the problem is doctors don’t understand the stress their patients are under because they have never gone through fertility treatment themselves.

Rewriting the medical textbook for fertility experts

Moreover, such gendered language places undue emphasis on the woman. “As a society, we haven’t ditched the age-old stereotype of ‘the barren old maid’,” argues Sarah Heywood, founder of The Journey, a platform set up to provide more evidence-based information about fertility.

“The truth is sperm counts on average are down more than 50 per cent over the last 40 years and the statistics show that if there is an issue with fertility, it is a third due to the female side, a third to the male and a third to a combination. So a predominately female focus is simply no longer representative of the reality of our modern times.”

This hints at the fact that there might be a much wider cultural problem to do with the very nature of gendered language itself.

“Most words evolve somewhat over time, but the semantic changes apparent in many gendered noun pairs shows a repeated pattern,” explains Jennifer Dorman, instructional designer in didactics at the language learning app Babbel. “Although the two terms may start out with equivalent status, it is the feminine form that often undergoes a semantic change to become pejorative and negative.”

Dorman suggests gendered language that perpetuates infertility stigma against women is in keeping with the way words associated with what is “male” and “female” change over time. She points to gendered noun pairs, which all started with equal status, such as master and mistress, sir and madam, and now have pejorative meanings attached only to what is female.

The most extreme example of this would be the words “hussy” and “knight” which came into use at roughly the same time, only for the former to deteriorate radically from its original meaning of housewife and the latter to ameliorate dramatically from its original meaning of boy.

Enshrining gender-neutral language in the context of fertility

This serves to illustrate the scale of the task when it comes to removing gendered language from the fertility journey and reducing infertility stigma as a whole. The expert consensus seems to be more education is needed about the subject to normalise the idea that conception can, in some cases, be difficult for both men and women.

“Fertility is a subject almost all of us will have an interest in at some point in our lives and the language we use around it is important because it can deeply affect a person’s perception of themselves and their psychological state,” Corda concludes. “Teaching people about infertility issues from a much younger age and normalising the conversation from here is what will help drive a greater awareness and understanding in society of the difficulties that many may face later in life.”

Fertility treatment for men and women