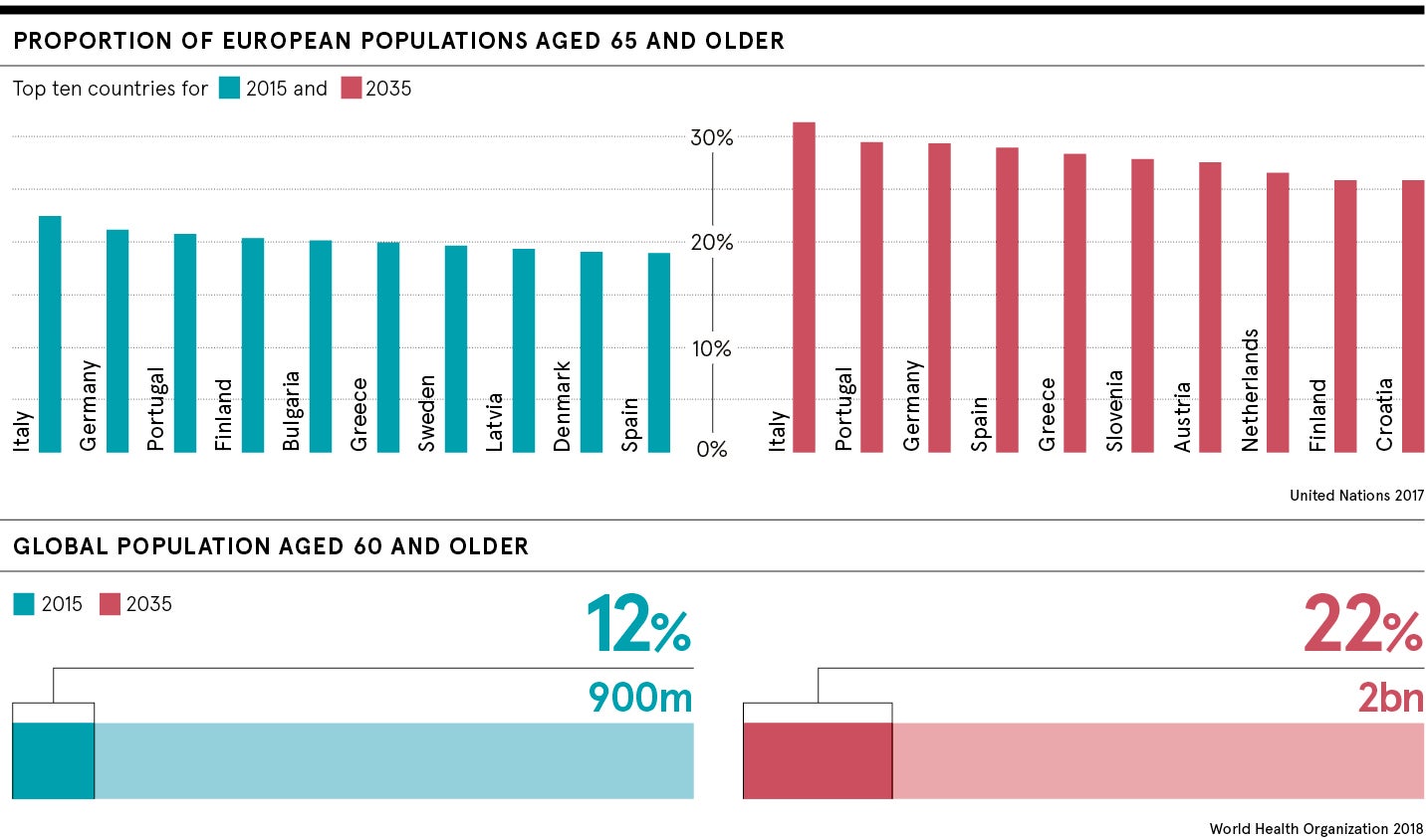

The statistics of an ageing population are a klaxon call of distress for policymakers and financial modellers desperate to balance the equation of supporting a demographic with voracious healthcare needs.

The long-standing medical approach of treating one disease at a time is at the end of its potential

Life expectancy in the UK has increased by around 30 years during a century garlanded with astonishing medical and public health advances. The over-65 cohort is expected to rise from its current level of one in six of the population to almost one in four by 2035, with people aged 85-plus reaching 4.6 per cent of the population, according to projections from the Office for National Statistics.

A triumph, no doubt, but one which needs to be tempered by the fact that the number of older people diagnosed with four or more diseases will double between 2015 and 2035. We are living longer but, for many, those extra years are blighted by ill health.

What kind of life faces people when they reach pension age?

The fiscal elastic holding the straining NHS in place is unlikely to cope with the elderly bulge, but a wave of research and innovation is offering scientific hope to challenges that will define both the health and wealth of future generations.

Factoring and finessing social policy will play a crucial role to ensure health and social care budgets resist the pressure-cooker forces brought by an ageing population, but scientific discovery is gearing up to declaw the ravages of ageing.

Mapping the human genome has supercharged biological understanding and this is being fed through prisms of technology and population data analytics to reveal disease trends and how to combat them.

Work, lifestyle and built environments have to improve to help society make the most of its extra years, but the transformative challenges and answers lie deep in our molecular and cellular structure.

“I refer to it as the longevity trap,” says Thomas von Zglinicki, professor of cellular gerontology and scientific director of the Institute of Ageing at Newcastle University. “You have a long life, but it can be pretty miserable on the personal side and on the societal side it becomes pretty expensive.

“Research says that we are expanding the lifespan, but we are not expanding healthy lifespan; people live longer, but they have more diseases for longer.”

The older population showing more illnesses per person than before

The Institute studied a cohort of 85 year olds and found all had multiple diseases; women averaging five and men four.

“None of them had no disease and this was quite shocking,” says Professor von Zglinicki, who has published more than 200 papers on the cell and molecular biology of ageing. “The long-standing medical approach of treating one disease at a time is at the end of its potential in that respect. Even if you could heal all the people with cardiovascular disease (CVD), they would have four or five diseases that are all related to the ageing process.”

Science is unpicking the corrosive influence of senescence, where cells stop dividing and lose their purpose which was once considered an irreversible factor of ageing. But work at Newcastle, and other centres around the world, has illuminated the destructive nature of these rogue performers that destabilise neighbouring cells and promote low-level inflammation, which has been identified as a trigger for many aspects of ageing.

Older people are the biggest consumers of healthcare yet we don’t do nearly enough research with them

“Working with the Mayo Clinic in the United States, we have shown that if you selectively kill senescent cells then you can postpone multiple age-related disabilities and disease,” he says. “We have not yet translated this into humans and, although that is a big step, the data is immensely encouraging.

“The first data from the US clinical trials will tell us whether we have a realistic chance of translating what we know from mice into humans and I think, optimistically, interventions that kill senescent cells will be beneficial. The earliest application will be in people who age faster than they should, those people who have had chemotherapy and radiotherapy treatment who get muscle wasting and cognitive, CVD and metabolic decline earlier than the normal population. To help these people is a realistic goal over the next ten years.”

New investment in improving quality of life for ageing population

This cautious confidence is shared across healthcare investment with venture capital heavily backing bioscience companies such Life Biosciences, a US startup, which swiftly completed a $50-million funding round in January to investigate eight pathways of age-related decline. Juvenescence, a UK biotech, drew in $50 million in funding last year to pursue artificial intelligence-generated programmes to support ageing populations.

But a sticking point in the headlong rush comes from a lack of clinical trials on elderly people with co-morbidities. They are a difficult group to corral for long-running tests and pharmaceutical companies focus on patients with one condition to give them “clean” results.

“There is a disconnect between scientific research and discovery, and getting that into a form that benefits patients,” says Miles Witham, professor of trials for older people at the National Institute for Health Research Newcastle Biomedical Research Centre.

“Older people are the biggest consumers of healthcare yet we don’t do nearly enough research with them. Our aim is to take what we learn in the laboratories and translate it into things that might make a difference to older people in their lives. It is not about extending life and making people live for ever, it is about improving quality of life and keeping people healthier for longer.”

Designing clinical trials that have logistical flex and address the real-life healthcare needs of an older group with multiple diseases will, Professor Witham believes, transform science from the aspirational to the applicable.

New goal is to be living well, not just living longer

The impact of ageing on the individual, society and the NHS is writ large in the almost emblematic old-age conditions of osteoporosis – three million sufferers in the UK with 500,000 receiving treatment for fragility fractures – and hip fractures that hit 65,958 in 2017, according to NHS figures.

But a five-year programme funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC) is identifying a whole-life approach to combat ageing and research conducted by Professor Cyrus Cooper, director of the MRC Lifecourse Epidemiology Unit at Southampton University, is already tackling the worst outcomes of musculoskeletal decline.

“The chilling facts are that 25 per cent of patients are dead within six months of a hip fracture and 50 per cent of those surviving cannot walk unaided, while one third of them has to go into a nursing home at a cost of £4.2 billion a year,” says Professor Cooper.

By developing a risk assessment tool combined with a bone-density scan, he was able to reduce hip fracture rates by 28 per cent in a trial of 12,500 women aged 70 to 85. The unit has also proved that supplementing vitamin D intake in maternal mothers boosts bone density in their children, potentially making them less susceptible to osteoporosis and fracture in the future.

“This tackles a once inevitable consequence of ageing with interventions at two time points, not just at the later stages of life,” he adds. “There is also a huge amount of evidence about the influence of diet and exercise in between, so it is important to look at ageing from a lifecourse perspective.”

A fusion of science, innovation and pragmatism is needed to open up a fresh landscape of healthier later years and, although eternal youth remains a fantastical concept, reducing the crippling impacts on an ageing population is a clear reality.

What kind of life faces people when they reach pension age?

The older population showing more illnesses per person than before