What springs to mind when asked to think of the things South Korea is most famous for? Kimchi, the ubiquitous side dish of fermented cabbages and radishes is likely to be a common first thought.

Next in line might be Seoul-headquartered tech giant Samsung, which last year shipped some 311.4 million smartphones, 96 million more than its greatest rival Apple. And it is probable that Hyundai will feature somewhere in the top three, after all, the automobile company’s Ulsan manufacturing facility turns out 1.6 million units a year, making it easily the most productive car factory on the planet.

Few would answer that South Korea is one of the leading countries in the world when it comes to having the lowest rate of fatalities caused by cardiovascular disease (CVD) though. But those who do would be absolutely right.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 17.7 million people died from CVD in 2015, representing 31 per cent of all global deaths. It is the number-one killer and in the UK specifically British Heart Foundation statistics show that 158,155 people died because of CVD in that same year. And yet in South Korea the number of fatalities caused by heart problems has dropped dramatically in the last 15 years.

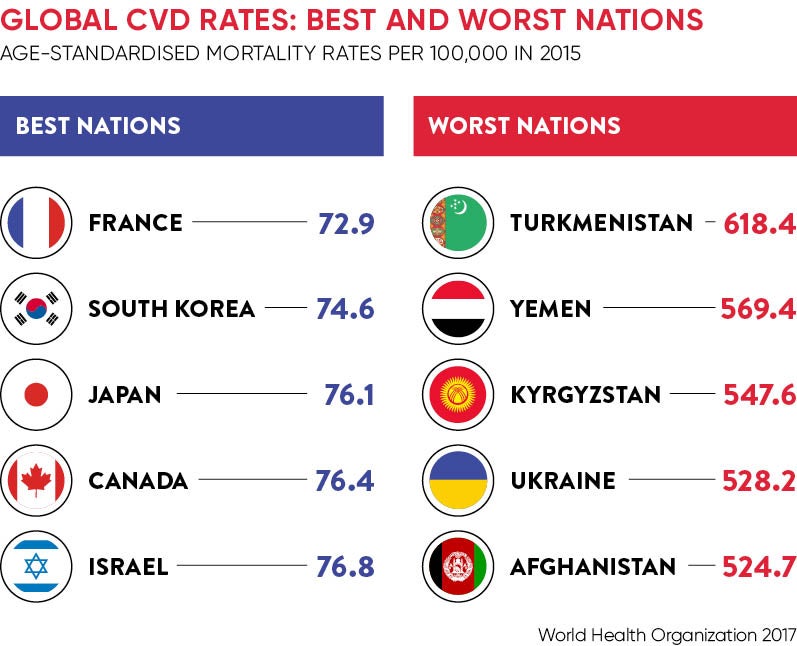

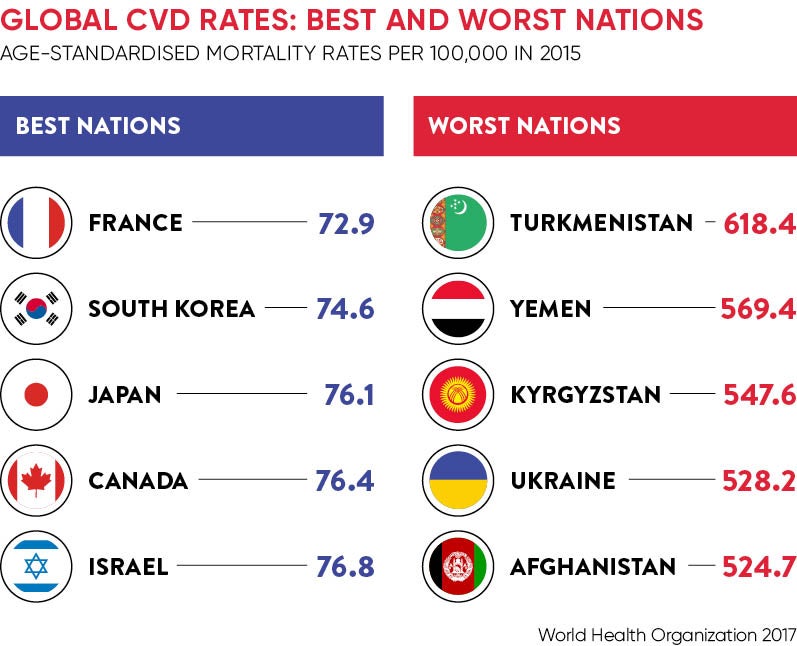

The WHO’s most recent findings, taken again from 2015 figures, indicate that South Korea has 74.6 CVD-related fatalities every 100,000 people a year, second only to France (72.9), using an age-standardised death rate as opposed to a crude reading, which can skew comparisons between countries. If you were wondering, the UK is currently 12th in the table, on 94.4.

South Korea’s low reading is all the more impressive when you consider how far and quickly it has fallen in the last decade and a half from 181.3 per 100,000 in 2000, to 138 five years later, and from 96.7 in 2010 to its present mark.

What has led to this unprecedented decline in deaths caused by CVD? Is it because of the national diet or countrywide lifestyle changes, or is it due to the increase in affluence and access to better medical care? As usual with complex questions such as this, the answer appears to be a combination of elements, says Gretchen Stevens, a technical officer in the Department of Health Statistics and Information Services at the WHO.

“South Korea is a very interesting country because it has had such a rapid change in this area,” says the American statistician, speaking from her organisation’s Geneva base. “Cardiovascular diseases are very complicated and there are quite a few lifestyle factors which are important distal determinants, such as tobacco smoking, physical activity, diet and nutrition. And there are more proximal determinants, including raised blood pressure, raised blood cholesterol and diabetes.

“Unlike wealthy countries, like France or Great Britain, which have had high-quality healthcare for two or three generations, South Korea even 20 years ago was a totally different setting. It is quite amazing that it’s now almost at the top of the rankings.

“Not so long ago it was a middle-income country and now it is classed as a high-income nation. So South Koreans can afford better medical care and that plays a part. That said it ends up being very hard to pinpoint one reason why the country is doing a little bit better than most others. It is probably a mix of numerous factors coming together.”

A surprising discovery is that coffee consumption could play a pivotal role, for South Koreans adore it. Early last year, The Korea Times reported that on average eight out of ten adults drink at least two cups of coffee every day, and a large number of them also grind and make their own coffee at home, in addition to café visits.

A 2015 study revealed that coffee lovers who consume between three and five mugs daily are less likely to develop clogged arteries. An international team, spearheaded by researchers the Kangbuk Samsung Hospital in the South Korean capital Seoul, found that those who drink a moderate amount of coffee have the least risk of producing coronary artery calcium, an early indicator of coronary atherosclerosis. This hardening of the arteries could lead to blood clotting, triggering a heart attack or stroke.

That South Koreans enjoy an alcoholic drink and cigarettes, and yet their CVD rates are so low, is a puzzle. A WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, published earlier this year, found that 39.3 per cent of the men in the country, aged 19 and above, smoke. Ms Stevens’ colleague Dr Hai-Rim Shin, who spends all of his time in Asia, says that the South Korean government’s recent push to establish a nationwide “multi-section medical service system” has balanced out the effect of smoking and is another reason why CVD-related deaths have decreased.

“Although there is a high prevalence of drinking and smoking,” he says, “high blood pressure and sugar levels are well managed thanks to greater accessibility to medical services at the primary healthcare level, which are covered by national health insurance. This offers high-quality medical diagnosis and treatment.”

In the last 20 years, a number of specialist cardiovascular centres have sprung up across South Korea, including a unit at the Gangnam Severance Hospital (GSH). Since opening in 1997, doctors at the facility have performed tens of thousands of coronary angiography and in the past decade have added a suite of intervention treatments, such as balloon dilatation and stent insertion using cutting-edge technology and techniques.

It is quite amazing that South Korea is now almost at the top of the rankings

An Irish diplomat, who wishes to remain anonymous, travelled to GSH to undergo a “very serious open-heart operation” and testifies: “It made a lasting impression. Firstly, I was treated in a highly professional manner at all times. It was not only the senior staff whose attitude was admirable, all the support staff were, too. My operation was a great success, due to the superb competence and expertise of my doctors, to whom I owe my life.”