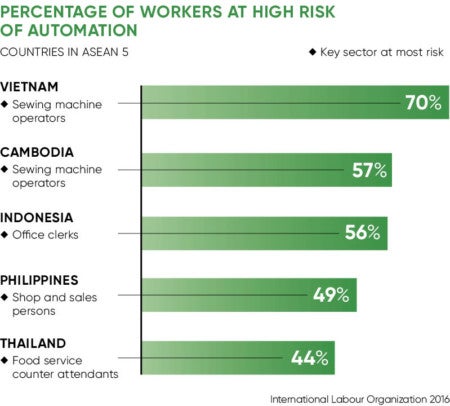

Automation and machine-learning are on the rise in South-East Asia, threatening the jobs of more than half the employed population of Cambodia, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines, known collectively as the ASEAN 5.

Research from the International Labor Organization (ILO) found that, across ASEAN-5 countries, 56 per cent of all jobs have a high risk of automation. Across the region, 27 million subsistence farmers and low-skilled agricultural labourers fall into the high-risk category of losing their jobs to their robotic counterparts.

The process of jobs being lost to machines could mean much hardship for workers if it is not handled well

In country-specific cases, 73 per cent of Thai workers in the automotive industry are at risk of being replaced by machines, while in the garment industries of Vietnam and Cambodia, 86 per cent and 88 per cent respectively are deemed at high risk of automation.

Phu Huynh, an ILO labour economist for Asia and the Pacific, who helped produce a string of reports on the impact of automation in the region, says the process of jobs being lost to machines could mean much hardship for workers if it is not handled well.

“If we talk about a vacuum where the technology is in place and there is nothing done in preparation for that process, then the fear is the workforce will have to adjust and that the adjustment may not be very pleasant,” Mr Huynh says. “It could be in the form of retrenchment, the form of workers shifting into more precarious jobs, more informal jobs. Really it depends on the specific country context and what sort of policies are in place.”

Automation and machine-learning are trends within the larger surge of artificial intelligence (AI), a phenomenon that seems incapable of slowing in pace. As the technology develops, lower cost barriers will see deeper and broader implementation across all aspects of life, including employment.

“Global market forces are going to mean that in the coming years more and more automation is going to be introduced into factories around the world,” says Sundeep Sanghavi, co-founder and chief executive of big data startup DataRPM. The business helps industrial companies better monitor and maintain their equipment, preventing problems before they arise.

“Most of the factories in South and South-East Asia are already investing in the industrial internet of things, but they are not seeing the same return in terms of revenue and downtime as other countries. Most of the companies are still in the prototyping phase, but they aren’t implementing this in the main production environment yet,” says Mr Sanghavi.

Should technology costs decrease to the point where it is financially justifiable to lay off workers in favour of machines, the threat of large-scale migration becomes a lot more real

For Mr Huynh and the ILO, it is when companies emerge from this development stage, particularly in the ASEAN 5, that job losses could lead to increased migration of low-skilled workers. Should technology costs decrease to the point where it is financially justifiable to lay off workers in favour of machines, the threat of large-scale migration becomes a lot more real, he says.

Readiness for automation in the region varies wildly. According to Mr Huynh, Singapore, Hong Kong and Japan are ahead of the curve, whereas governments in Thailand and Malaysia are starting to put in place some of the policies needed to prepare their workforces.

In Thailand, the government’s flagship programme, Thailand 4.0, is being posited as the scheme that is going to get Thailand into shape before automation inflicts an adverse impact on the nation’s workforce. With a large population of unskilled and semi-skilled workers, Thailand worries that 23 million people are at risk of losing their jobs if automation is as ruthless a process as people fear. To that end, the aim of Thailand 4.0 is to create a value-based economy with less social disparity. This includes setting up 20,000 farming households with the technology and training they need to be prepared for the impact of new technology.

Perhaps industry figures like DataRPM’s Mr Sanghavi can allay some fears. He believes the impact of technology and automation will be positive, and help increase factory safety in a way that can protect people who are working with large, and potentially dangerous, equipment.

“The real benefit of these new technologies is that workers now have the same insights at their fingertips that used to take big teams of data scientists months to comb through,” Mr Sanghavi says. “Increased automation is a new layer helping workers, rather than replacing them.”

The one thing that does seem certain is that automation will impact the region. Mr Huynh says the evidence of automation’s unstoppable march is already apparent in sectors such as the automotive and textile industries. How this affects individual countries, he says, will be up to their governments.

“Automation is picking up due to this need to increase productivity, this need to supplement and complement workers to make the production prices more efficient,” he says. “A lot is going to depend on what happens in terms of policy and in terms of what governments do to prepare for this process.”