Plenty of media attention has been devoted to robots replacing lawyers. Conversely, some industry players claim that artificial intelligence (AI) is simply a buzzword used to sell software to law firms.

“Are many AI-badged products just rule-based decision-making tools?” asks Alex Smith, platform innovation lead at LexisNexis UK. “What counts as AI?”

Adding-value

AI in business has moved beyond process automation to include natural language processing and machine-learning, whereby computers are trained to interpret information and adjust their processes to user feedback. Rather than searching for keywords or strings of words, the software reads and understands information, so its findings and recommendations are based on contextual elements.

Gerard Frith, chief executive of AI consultancy Matter, explains how AI adds value by modelling and reapplying expert knowledge in a fast, scalable way. AI enables law firms to complete repetitive tasks that involve legal precedents and specific know-how dramatically faster, freeing up lawyers to concentrate on more complicated tasks.

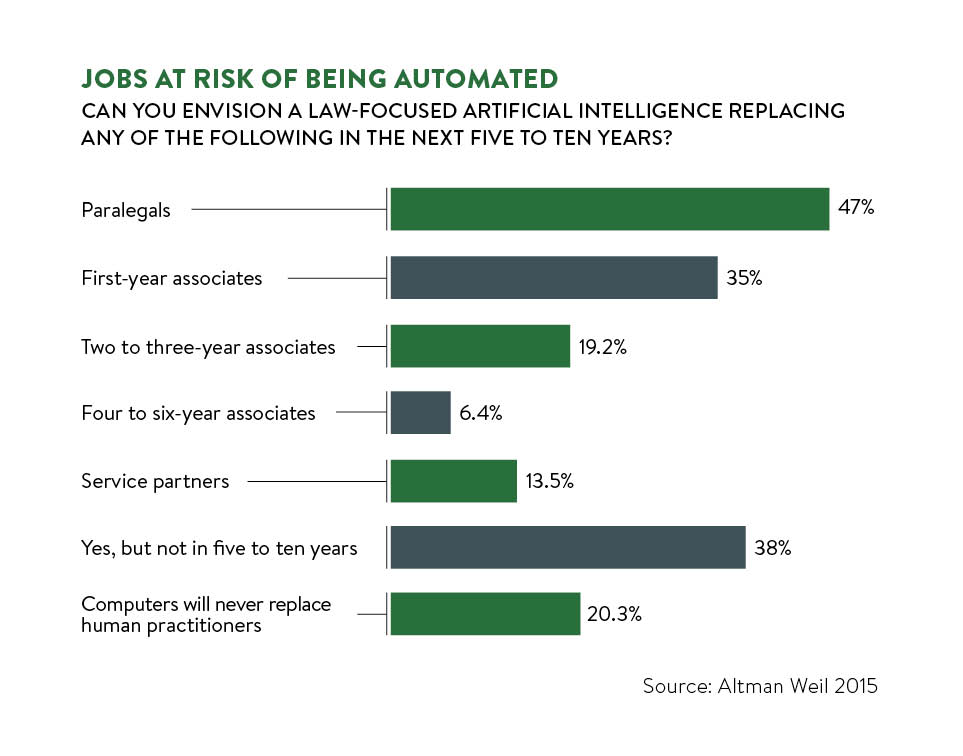

Applications that combine natural language processing and machine-learning are conducting legal research that was previously undertaken by junior associates. Other AI-powered tools handle administrative and management tasks such as work intake and allocation.

AI adds value by modelling and reapplying expert knowledge in a fast, scalable way

US firm BakerHostetler recently employed “artificially intelligent attorney” ROSS in its bankruptcy practice. Some 20 firms are also trialling ROSS.

LONald, Berwin Leighton Paisner’s “robotic contract lawyer”, powered by RAVN’s applied cognitive engine supports the law firm’s real estate practice, handling due diligence on property transactions. It connects with the Land Registry site to verify property details and collates the results in a spreadsheet.

Robots and due diligence

So should lawyers worry about being replaced by robots? Bob Craig, chief information officer at BakerHostetler, does not think so. “ROSS is not a way to replace our attorneys – it is a supplemental tool to help them move faster, learn faster and continually improve,” says Mr Craig.

Although legal work typically involves extracting information from contracts and other documents, as ROSS chief executive and co-founder Andrew Arruda and others say, lawyers’ core skills are around interpreting that information into legal advice.

Kira Systems’ due diligence and contract analysis software facilitates mergers and acquisitions (M&A) by analysing documents relating to the target company to identify clauses that could affect the deal.

Co-founder Noah Waisberg explains that due diligence represents 30 to 60 per cent of the work in many transactions. In addition to producing 20 to 90 per cent time-saving on contract reviews, because Kira’s system is trained by experienced practitioners, it helps to “institutionalise a firm’s knowledge advantage” by allowing junior lawyers to benefit from the skills of their senior colleagues, he says.

Firms developing in-house AI-powered tools include Linklaters’ Verifi, which checks client names for banks, and Pinsent Masons’ TermFrame, which analyses loan agreements and guides lawyers through transactions.

Legal AI is currently pointed at specific tasks. This is because the AI engine is trained to identify specific data points and learn from user feedback. As Mr Waisberg explains, it took more than two years to develop Kira’s due diligence software.

Meeting client needs

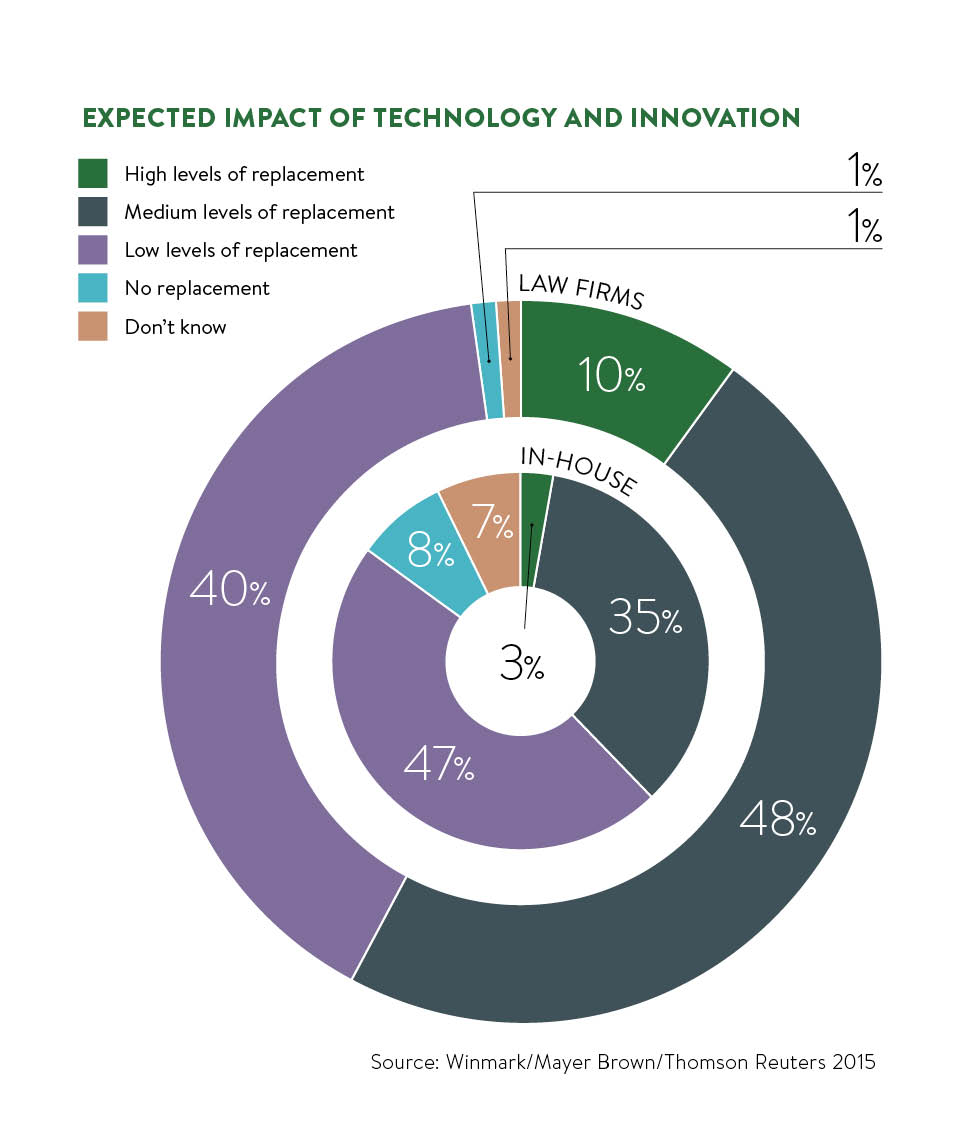

The growth of AI in legal is fuelled by client demand. “AI is happening now and firms that act quickly will reap the benefits,” says legal futurist and author Chrissie Lightfoot. “But most firms don’t want to break the business model so they won’t change until they are told to by their clients.”

Riverview Law chief executive and founder Karl Chapman agrees that client companies are driving AI adoption. Riverview Law’s Kim – knowledge, information, meaning – is an AI platform powering a range of virtual assistants that support corporate legal departments.

Based on the IBM Watson platform, Kim assimilates documents and uses the information to build workflows, reflecting the reference by Professor Harrick Vin, vice president and global head of Digitate, at the AI Summit in London, to AI representing service-as-software as opposed to software-as-a-service. “Kim has been described as virtual software development AI,” explains Mr Chapman.

Kim’s triage capability manages a legal team’s workload, allocating cases to the appropriate in-house or external adviser and generating real-time management information about the department’s work in progress.

AI is not just about back-office administration, legal research and know-how – it is also front-end, client-facing services and business development

At enterprise level, Kim supports decision-making. “For example, Kim can manage IT supplier contracts, interrogating all contracts and work in progress, and flagging up any discrepancies, conflicts or potential issues,” Mr Chapman adds.

Kim helps lawyers work effectively by delivering relevant information and suggesting solutions in real time. Like ROSS, LONald and Kira, Kim is generally accessed online, although it can be installed on-premise.

Ms Lightfoot emphasises that AI is moving up the legal vertical. It is not just about back-office administration, legal research and know-how – it is also front-end, client-facing services and business development.

According to Neota Logic chief executive Richard Seabrook, the “last mile” to wholesale AI adoption is “to include expertise in software”. Neota’s smart apps tackle exactly that, encapsulating legal knowledge, reasoning and judgment to provide self-service real-time legal advice.

Greg Wildisen, Neota’s international managing director, offers an example. Taylor Wessing used Neota to develop an interactive app that clients can use to find out whether they are subject to the People with Significant Control rules.

“Clients can click on a link and answer ten questions to find out immediately whether they are affected,” says Mr Wildisen. This application of AI is infinitely scalable. “Each app offers the ability to solve a particular problem for an unlimited number of parties concurrently,” he says, adding that AI has the potential to extend legal services to people who have been failed by the justice system.

Innovation at the core

London’s first LegalTech Hackathon, which was organised by Legal Geek to help Hackney Community Law Centre deliver more cost-effective legal advice, was won by Fresh Innovate, a team from magic circle firm Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer. The Hackathon produced AI-powered tools including a triage service for incoming queries and a comprehensive case management solution built on the Neota Logic platform.

AI is impacting every part of the industry. Last year, Stanford University computer science student Joshua Browder from north London developed DoNotPay.co.uk, a free online chatbot that handles parking ticket appeals instead of a lawyer. It is based on English law, but there are plans to expand the service to the United States.

Key benefits of AI include enhanced competitive advantage as firms that invest in AI can take on more work at competitive rates while maintaining their margins.

As legal AI is generally cloud-based, the barriers to adoption are low. Virtual assistants RAVN, ROSS and Kira could enable smaller firms to extend their services when necessary without employing additional support staff.

AI’s scalability supports business development. Once clients realise that a firm can turn around large volumes of documents extremely quickly, they are likely to make use of this capability.

Legal innovation is one of 2016’s big stories and this includes larger firms investing in innovative technology. Dentons’ NextLaw Labs was an early investor in ROSS. Big legal publishers are following suit, perhaps reacting to AI-powered legal research assistants. Last year LexisNexis acquired Lex Machina, an AI-powered engine that applies natural language processing to public court documents to predict outcomes in intellectual property litigation.

Changing business structures

Entrusting tasks to AI will impact on the structure of law firms and the industry. Milos Kresojevic, enterprise architect at Freshfields, envisages legal AI leading to profound changes in roles and training.

“There will be a shift in the skills required to leverage the productivity potential of new, smart technologies, with an increased emphasis on cross-disciplinary engineering and scientific skills and the ability to adapt to a workplace that is staffed by people and machines,” says Mr Kresojevic, who is looking at how AI can bring end-to-end efficiencies while considering the impact on IT governance of task-specific quick-win solutions.

David Halliwell, director of knowledge, risk and legal services at Pinsent Masons, agrees. “The requirements of data and system integration mean that firms will need in-house capability to develop, exploit and integrate AI and other systems to rapidly deploy solutions for specific deal and client needs. Clients will get used to seeing data scientists on deal team sheets as AI skills move from back office to front office, and end up leading and driving deals.”

RAVN chief executive Peter Wallqvist is looking to lower the barriers to legal AI. “The next step is to integrate AI into the fabric of the business by creating more interfaces with firms’ IT systems so people don’t have to understand AI to benefit from it,” he says.

AI in the legal sector is incrementally disruptive and its impact should not be underestimated. “Law firms sticking to a traditional model may find themselves disrupted if they do not leverage the technology,” concludes Alexander Duisberg, partner at Bird & Bird.

CASE STUDY: ROSS AT BAKERHOSTETLER

On May 11, US law firm BakerHostetler announced that it had hired artificially intelligent attorney ROSS for its bankruptcy practice. “We believe that emerging technologies like cognitive computing and other forms of machine-learning can help enhance the services we deliver to our clients,” says chief information officer Bob Craig.

ROSS, developed by ROSS Intelligence, fulfils a professional support lawyer role, undertaking legal research to support BakerHostetler’s attorneys by finding appropriate precedents and other documents, and answering legal questions that relate to the matters they handle.

ROSS is built on the IBM Watson AI platform. As Andrew Arruda, chief executive and co-founder explains, rather than typing in a word or phrase, you can ask ROSS a natural language question in the same way as a junior lawyer might consult an experienced colleague. ROSS then reads through the law and legal precedence, gathers evidence, draws inferences and returns an evidence-based answer.

Although ROSS can be programmed to include voice recognition and voice-to-text capability, lawyers prefer to type their queries rather than speaking to the computer.

ROSS incorporates supervised and unsupervised machine-learning. “Our legal specialists have trained ROSS and helped to point it towards appropriate answers to various questions,” explains Mr Arruda. “We also encourage users to up-vote and down-vote passages to confirm or deny ROSS’s interpretation of the question. Every time a user interacts with ROSS, it becomes smarter.” ROSS is accessed as an online subscription service.

ROSS Intelligence was the first company backed by NextLaw Labs, the innovation arm of international law firm Dentons.