US basketball superstar Michael Jordan recently opened a second medical clinic. Located in a poor part of Charlotte, North Carolina, the clinic aims to provide primary and preventative care for those with little or no health insurance. Jordan, who worked with integrated healthcare provider Novant Health to open the clinic, personally donated $7 million towards the project.

“The impact of the first clinic has been measurable and if COVID-19 has taught us anything, it is the importance of having accessible, safe and quality care in communities that need it most,” according to Novant Health’s chief executive Carl Armato.

Integrated healthcare models, such as those provided by Novant, are becoming more common in America amid massive industry consolidation. But they’re just one potential fix to a system plagued by escalating costs and an uninsured or underinsured population. In the case of Michael Jordan’s clinics, Novant provides free or reduced care to patients with household income up to 300 per cent of the federal poverty level of $26,200 for a family of four.

The question of health insurance is political

In past decades, numerous presidents, including Roosevelt, Truman, Nixon, Carter and Obama, have tried to reform health insurance in America. Only President Barack Obama, with the Affordable Care Act (ACA), managed to pass legislation to reform insurance and make healthcare more accessible. However, it has come under attack by Republicans and is currently being debated in the Supreme Court for being unconstitutional.

With Democrat Joe Biden as the president-elect, it is likely that many of the things President Donald Trump did to weaken the ACA will be reversed. But beyond that, sweeping change is unlikely.

“I’ve been studying this for 30 years. And the first reference I could find to healthcare costs being a huge problem for many hospitals was in 1961. I’m not saying it will never change, but you know, it just goes on,” says Professor Sherry Glied, dean of New York University’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service.

One of the many problems with America’s complicated patchwork of healthcare and insurance systems is there are few ways to control costs. US drug prices have risen 33 per cent since 2014, according to research by GoodRx, an online platform that helps Americans find the lowest prices of prescription medication. In addition, the cost of all medical services combined have increased 17 per cent since 2014, the company found. Meanwhile, the number of uninsured people increased in 2019, the third year in a row, according to data from the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Are integrated systems the secret to affordable care?

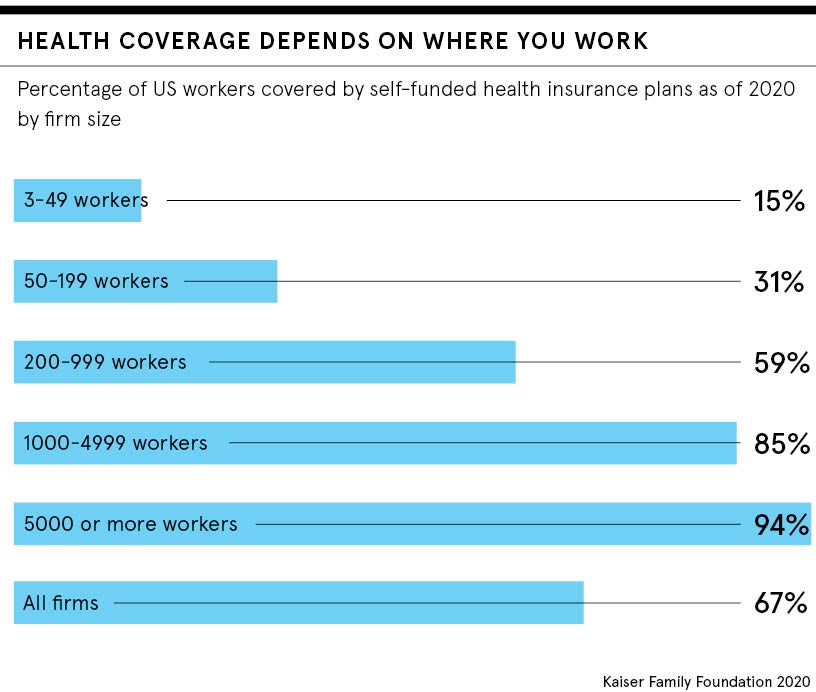

Nearly half of health insurance in America is provided through an employer. These plans are expensive. Annual family premiums for employer-sponsored health insurance was $21,342 in 2020. Since 2010, average premiums have increased 55 per cent. Not only that, but about 83 per cent of these plans have an average deductible of $1,655.

Industry experts hope more integrated systems, which bind together insurance, hospitals and provider clinics into one, may help put pressure on costs. In recent years, there’s been a wave of vertical integrations with health plans buying pharmacy benefit managers or primary care physician groups or a hospital system buying oncology clinics.

This trend is relatively new and it will take a long time to mash some of these giant companies or systems together. But it’s been encouraged on the hope integration could lead to better co-ordination across the various parts of the patient’s healthcare journey, drive down costs and improve health outcomes, says Chris Sloan, associate principal at Avalere Health, a healthcare consulting firm.

“In theory, you can align the incentives to reduce costs and drive towards better health outcomes, rather than just getting paid on a fee per service basis,” he says.

Could the President-elect turn healthcare on its head?

In the last four years, the Trump administration has sought to eliminate or weaken the ACA by cutting marketplace subsidies and allowing “junk health plans” that steer young, healthy people into cheap, short-term policies, which consequently raises costs for everyone else. Many of these actions did not need to go through the legislature, which means everything they did can be reversed, says Glied.

Industry experts expect Biden, along with a Democrat-controlled Congress, to undo or tighten up some of the loosened restrictions Trump put in place. Biden could bulk up subsidies for low-income individuals who otherwise could not afford health insurance. He could also strengthen protections for people with pre-existing conditions by limiting out-of-pocket costs.

Among the president-elect’s more controversial proposals is a public insurance option. One potential upside is a public plan would presumably pay prices similar to those Medicare pays.

“The idea would be to create competitive pressure for private insurance to work a little harder and negotiate some better discounts with doctors and hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies,” says Karen Pollitz, senior fellow at the Kaiser Family Foundation. However, the likelihood of such a proposal passing with a Republican-dominated Senate in place is extremely unlikely, says Avalere’s Sloan.

The most likely outcome in the next four years is nothing changes

Meanwhile, some surveys show that dissatisfaction with high healthcare costs is growing. According to a Gallup poll from December 2019, 63 per cent of Americans say the country’s healthcare system is in “a state of crisis” or has “major problems”.

Yet support for a government-run programme remains mixed. The majority of Americans believe the government should be responsible for ensuring everyone has insurance, but most also reject the idea of a government-run healthcare system. These mixed feelings are playing out in politics. ACA was “a pretty targeted” bill when it passed in 2010, says Sloan, noting it mostly targeted the individual market. Even so, the move “dominated the political discussion for the next six years with voters fighting to repeal it or keep it or support it or bring it down”, he says. “The most likely outcome in the next four years is nothing changes.”

US basketball superstar Michael Jordan recently opened a second medical clinic. Located in a poor part of Charlotte, North Carolina, the clinic aims to provide primary and preventative care for those with little or no health insurance. Jordan, who worked with integrated healthcare provider Novant Health to open the clinic, personally donated $7 million towards the project.

"The impact of the first clinic has been measurable and if COVID-19 has taught us anything, it is the importance of having accessible, safe and quality care in communities that need it most," according to Novant Health's chief executive Carl Armato.