Millions of people will be forced to either retire in poverty or “work until they drop” unless the government goes further and quicker with its programme of pensions reform.

So says Sir Steve Webb, who as pensions minister under David Cameron was a prime mover in the introduction of the Department for Work and Pension’s (DWP) flagship auto-enrolment scheme six years ago.

Going to work solely because the state pension isn’t enough to live on and your personal pension is puny isn’t a good state of affairs

Now director of policy at Royal London, Sir Steve believes that unless minimum contributions to workplace pensions rise to “a more realistic level”, maintaining a decent income in retirement will be beyond the reach of many.

“There are literally millions of people in their late-40s and 50s who are too young to benefit from the lucrative final salary or defined benefit (DB) pensions which are either now closed to new members or being shut down,” he says.

“Yet many of these older workers may already be too old to build up a decent sum from what has replaced DB, the so-called defined contribution schemes which tend to be far less generous.”

While Sir Steve says he is in favour of people working longer if they want to, being forced to stay on the treadmill purely to pay the bills is another matter.

“Going to work solely because the state pension isn’t enough to live on and your personal pension is puny isn’t a good state of affairs for individuals, or for business or society,” he says.

Last December, the DWP’s own review of auto-enrolment found that some 12 million Britons or 38 per cent of the working population overall are still failing to save enough for a comfortable retirement.

Although overall opt-out rates for the new pension savings system have been generally lower than expected, workers aged 55 and above are three times more likely to drop out than younger colleagues, even though current minimum contribution rates are just 1 per cent each for employees and employers.

With two contribution price hikes already on the horizon – they rise to 5 per cent in total in April and to 8 per cent in April 2019, sums described as “wholly inadequate” by Sir Steve – there are fears that drop-out rates among the 55-plus age group may continue to rise.

“When you look at this issue in more depth and realise how many people in this country have literally never saved, let alone saved for retirement, you begin to realise how big a problem we are building up for the future,” he says.

Aegon head of pensions Kate Smith believes that older workers represent a “lost generation who have been left behind” by the recent pension changes and she too urges the government to do more to help them.

“We hear a lot about millennials being short-changed by various policies, but in terms of auto-enrolment, they do at least have the luxury of several decades in which to build up a decent fund for later life,” she says.

“For the millions of workers who had fully expected to retire in the comparatively near future, but who can no longer afford to, the outlook is very different. When you add in the burden of expensive caring responsibilities, you begin to see that we have a perfect storm.”

Although equity release lending broke through the £3-billion barrier for the first time in 2017, Ms Smith advises homeowners looking for a quick cash injection to tread cautiously.

“Selling equity in your home not only deprives your children of becoming homeowners, but may be wholly inadequate when it comes to funding 20 or more years after retirement,” she says.

Although the DWP’s decision to lower the minimum auto-enrolment age from 22 to 18 earns praise from Ms Smith, she believes that obliging workers to opt back in once they hit state pension age is a mistake.

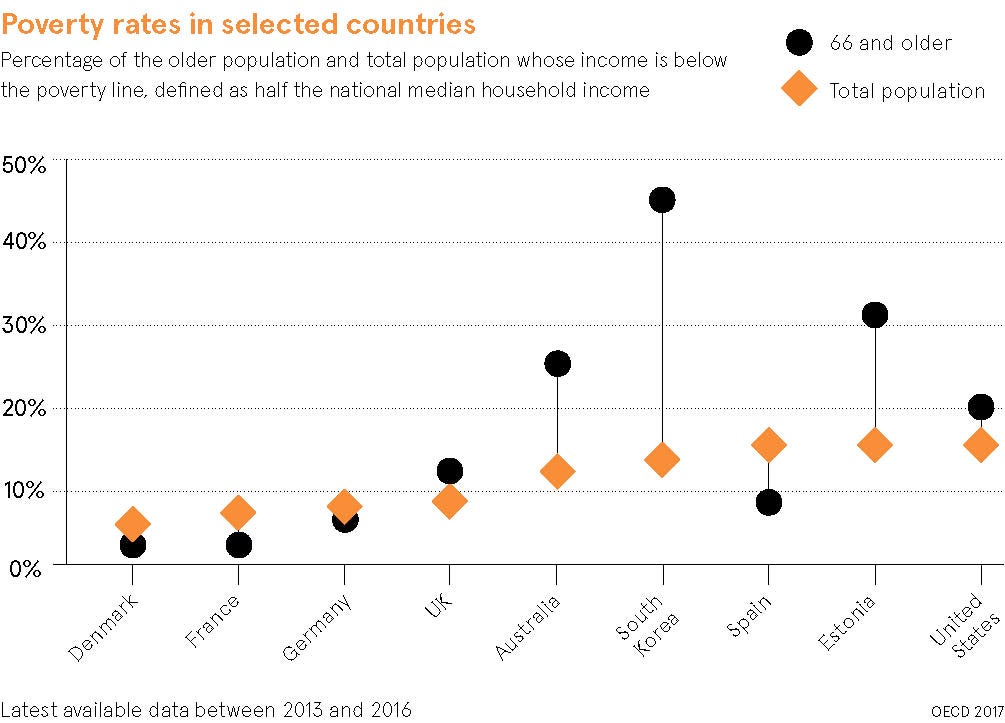

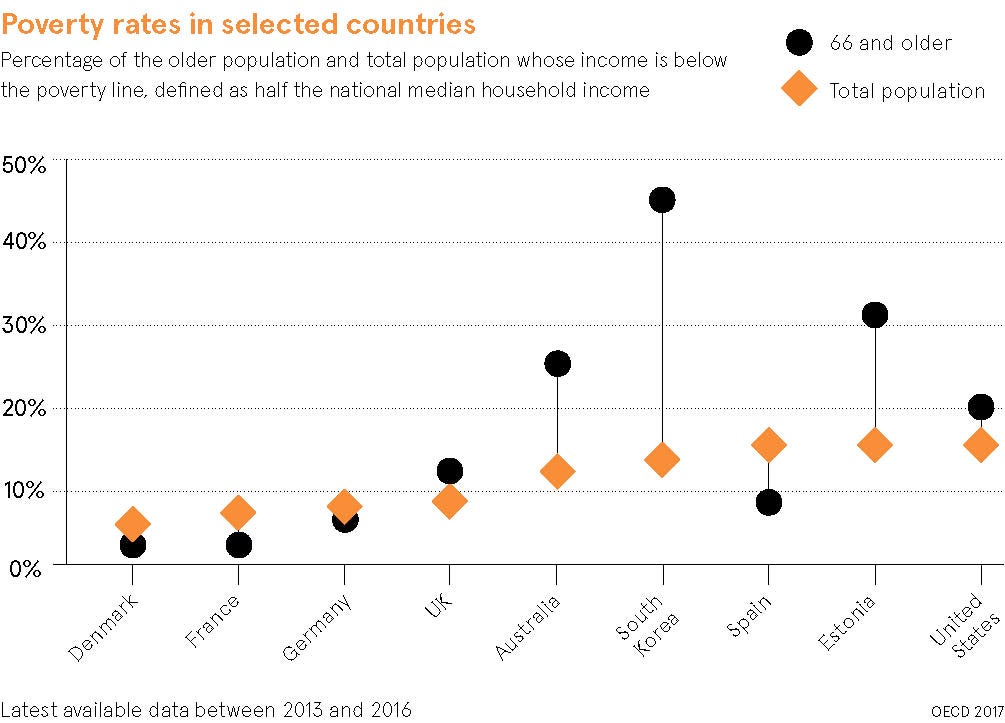

“Many more people are enjoying longer working lives and they should be included in auto-enrolment just like other workers. Removing the younger age limit, but leaving the older one in place is a missed opportunity in the fight against pensioner poverty.”

For Sir Steve, another major area of concern is the decision not to include the country’s 4.8 million self-employed people, many of them in the older age bracket, in auto-enrolment at this stage.

According to recent data from the Office for National Statistics, as many as 45 per cent of self-employed people aged between 35 and 55 have literally zero pension wealth; a finding which Sir Steve describes as “truly shocking”.

For Aviva’s head of retirement solutions policy John Lawson, there is much to celebrate in the new workplace pensions landscape, however.

“It’s a great shame that so many people in their 40s and 50s think they are too old for auto-enrolment because nothing could be further from the truth,” he says.

“Unless you have high-interest debts such as mortgages, which should always be paid off first, auto-enrolment is an absolute no brainer, particularly if you are fortunate enough to have an employer who will match your contributions above and beyond the minimum.”

While Mr Lawson agrees that for those already close to pension age, a workplace pension may not be sufficient to fund an entire lifestyle, he believes opting out on age grounds alone may be a costly mistake.

“Whether it’s augmenting the state pension, doing up your kitchen or having a holiday, building up cash through auto-enrolment can help retirement run more smoothly,” he says. “In my view, auto-enrolment rates among the 50-pluses should already be at 100 per cent.”