01 MARRY FOR RIGHT REASONS

Industries are being transformed by the third industrial revolution. Digital technology is continuing to advance efficiency, service and to create new ways of working. For some firms this is the world into which they were born. For others, this world has been thrust upon them.

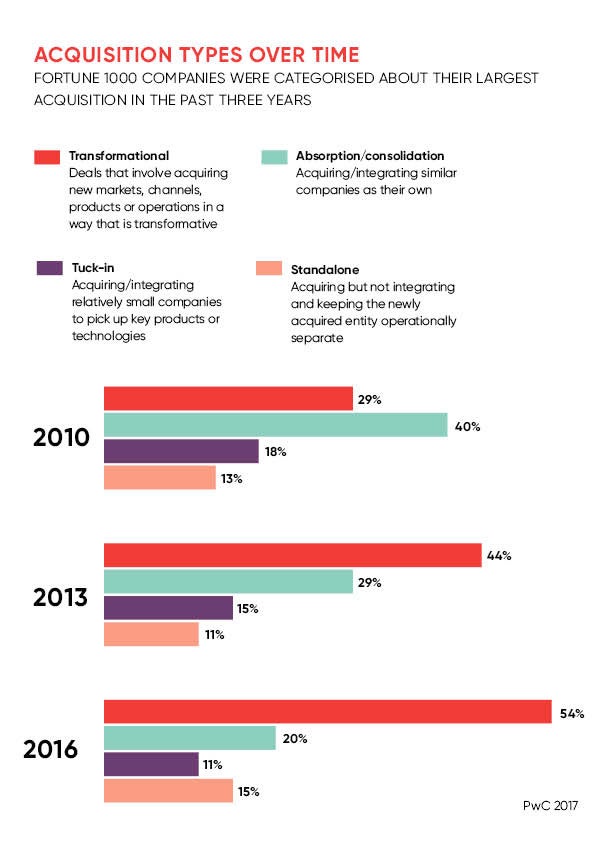

Consultancy PwC’s 2017 M&A Integration Survey found that among the merger and acquisition activity it studied, transformation deals, involving one firm acquiring new markets, channels, products or operations, which will be transformational to the combined entity, made up 54 per cent of all deals in 2016, up from 29 per cent in 2010.

At the same time the proportion of deals that involved an acquisition of a smaller firm to pick up products or technology, or consolidation between similar companies, both fell.

Among M&A professionals, the polarisation of growth and decline in these types of deals is not so clearly defined.

“M&A is very cyclical,” says Richard Cranfield, global chairman of corporate practice and co-head of the financial institutions group at law firm Allen & Overy. “What we have seen from 2013 through to the current period is an uptick in M&A in most sectors globally. The drivers may be transformational – new markets, new products – or just buying growth and we have been in an environment of low growth. Anecdotally, business-as-usual M&A, such as bolt-ons, is still going on; the bigger deals are just proportionately more prominent.”

Typically, the activity seen within one sector cannot be generalised to other business areas. There are industry-specific changes that drive firms to integrate. For example, among asset managers there is a pressure on fees leading them to merge their operations to gain scale and increase synergies. Large-scale brewers have been consolidating for years, but a new raft of small-scale breweries has created a different competitive dynamic.

Within many other sectors, digital-first companies, which have new models for running longstanding businesses, are being acquired to move business models into the 21st century.

David Lomer, co-head of Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA) M&A at investment bank J.P. Morgan says: “There are a number of recent deals, involving companies which are looking to diversify because of new economy opportunities, where they feel they should begin to buy exposure to a separate, new business model.”

02 UNITING TWO FAMILIES

Like parents who remarry, the chief executives of merging companies may feel a great attraction, but struggle to get their immediate dependents onboard with the idea. To integrate the two firms is traditionally seen as critical to the success of the deal.

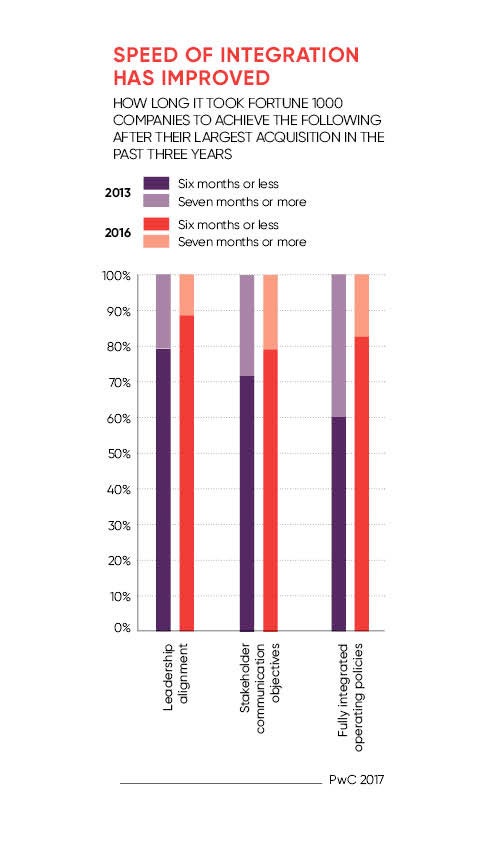

PwC found that the speed of integration has increased across several measures since 2013, with leadership alignment, stakeholder communication objectives and the integration of operating policies increasingly taking less than six months to achieve. The achievement can be credited to the evolution of skillsets and technology application, often within the acquirers themselves.

Allen & Overy’s Mr Cranfield says: “Most of the larger clients we deal with have dedicated teams for M&A, and integration and strategy. The in-house teams have a massive advantage of understanding the business, whereas the external advisers tend to be more generalists by background, with a few notable exceptions.”

The board of a firm might see a strategic target and think it makes sense to combine because together the firms will create more value than they would alone. That is ultimately quantified through synergies which the teams involved must understand.

“Working backwards, you need to have a real sense of where synergies are going to come from,” says J.P. Morgan’s Mr Lomer. “That requires you to prefigure how you want a business to be run. Each individual role may impact small financial sums, but what they portend is a vision for how the firm will be run overall. Whether you have five divisions or three, which currency you will report in, whether you slice sales by geography or by product? They have very important cultural, strategic and personnel consequences.”

To make this assessment, you need to understand the “body language” of the transaction and determine if is a straight merger, where both sides will share in those synergies, or whether it is a takeover and the acquirer is going to pay a premium. According to the principles of value-matching, the acquirer should not be paying more of a premium than they are going to realise via synergies. When paying a premium, this must be very clearly justified to investors.

In some cases, particularly those involving an evolution of the business model, it is imperative that the larger partner does not smother the smaller.

Jana Mercereau, head of corporate M&A at investment consultancy Willis Towers Watson, says: “There are different levels to which the firms can integrate. A business can worry that it might kill what it buys. In these circumstances, we are hearing more and more that firms are considering not fully integrating a business or integrating over the longer term. The question is then how to achieve synergies under that model?”

However that is planned, it must be explained to investors and stakeholders, to ensure communication is clear and operational lines are well drawn.

“Companies and their advisers need to be transparent on the strategic rationale and the quantification of synergies that are going to be procured for the good of shareholders, and for the good of the target shareholders,” says Mr Lomer.

03 AFTER THE WEDDING

Some firms are serial acquirers; others will be managing a deal for the first time. What experience has taught those who repeat the process is the value of preparation for after the event. Yet even they can get it wrong.

“There are examples where people, who have done a lot of M&A, have really failed to address some basic integration issues,” warns Allen & Overy’s Mr Cranfield. “You find a number of financial institutions, who have done a lot of M&A, that are running multiple legacy IT platforms because they have never been able to get across the hurdle of moving from one platform to another.”

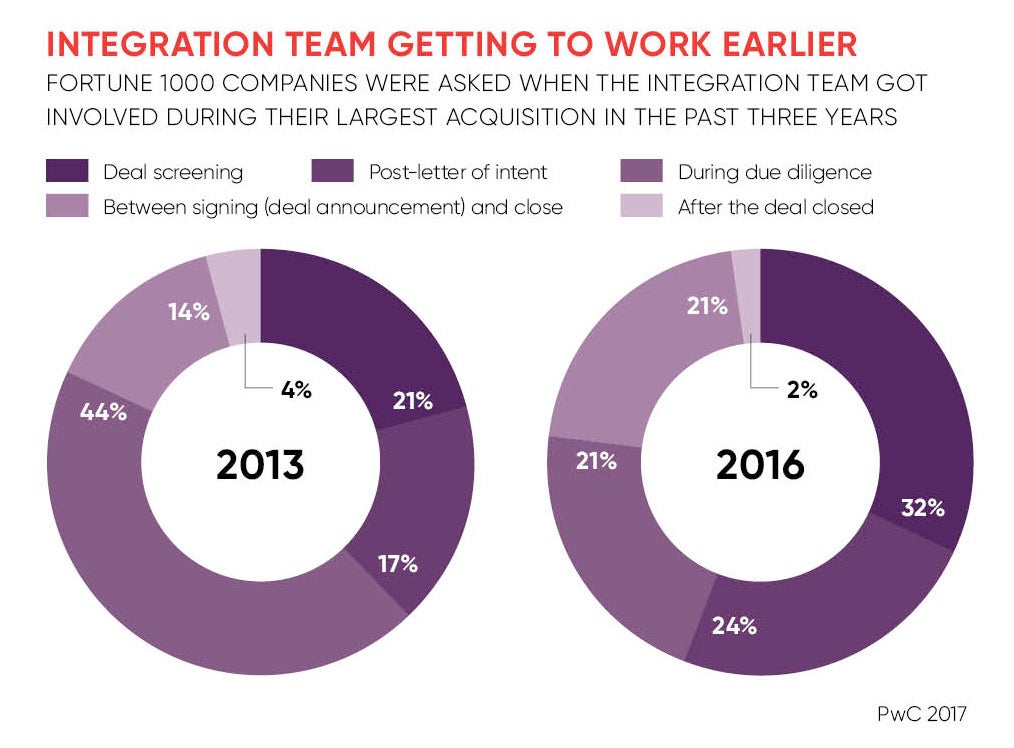

The good news is that PwC found the point at which integration teams were becoming involved in deals had moved from the due diligence phase of the process to earlier stages and the proportion getting involved only after the deal had closed had halved. That suggests senior management are increasingly aware of the value that post-deal planning creates.

“You have to have that vision to articulate how you are going to create X hundred million pounds of synergy out of a merger,” J.P. Morgan’s Mr Lomer notes. “That also works back to the need for your post-deal integration strategy to be well planned.”

This can be particularly important in transformational deals where the process of integration is not simply to absorb the acquired business and merge the two entities.

Ms Mercereau at Willis Towers Watson says: “There are acquirers that want to learn from the smaller business and so look at integration in the longer run, almost reverse osmosis, to change their own business model.”

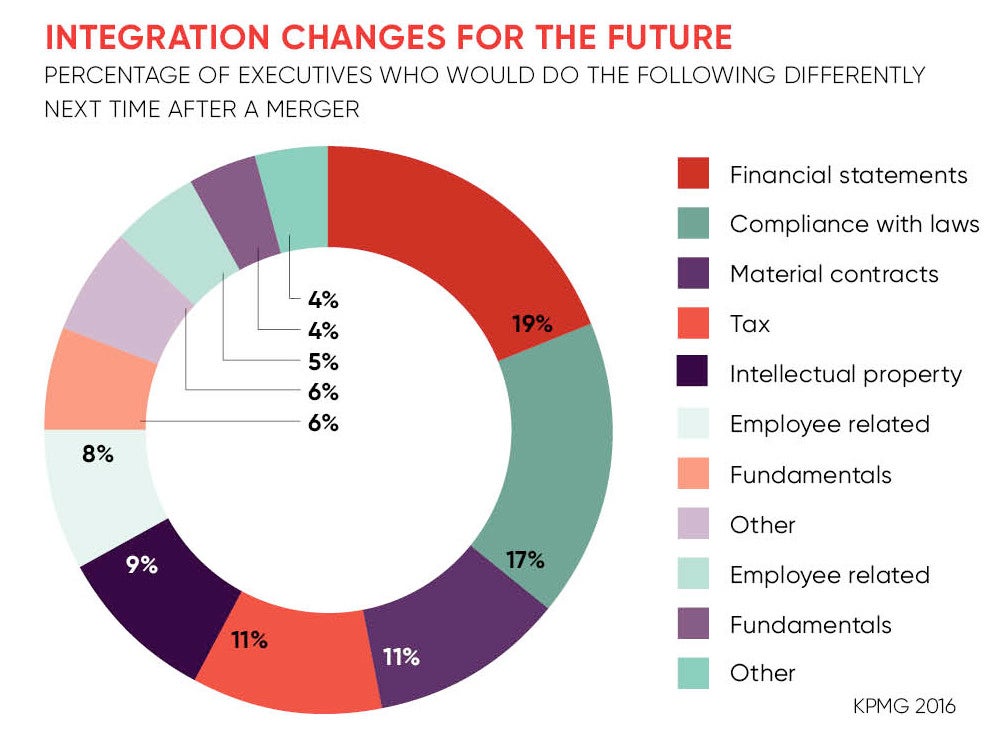

In its 2016 Insights research note entitled Post-merger integration, consultancy KPMG found that earlier planning for the post-deal situation was the thing most executives would change about a deal they had made, with awareness of cultural differences, better overall planning and appointing a post-deal team also ranking highly.

“We tend to hear organisations wishing they had paid more attention to the cultural differences that exist between parties and the risks associated with the deal,” says Hilary London, EMEA general manager at virtual data room provider Merrill Corporation. “As a result companies are spending more time and money on scenario planning and improving their business process management.”

It is a mistake to consider such aspects “soft” elements, which are quite apart from financial ones; the costs of not engaging with the post-deal process can be very real.

“Even the main steps that have to take place between announcement and closing can be frustrated by a lack of clarity on what the new group is going to look like and how it’s going to be run,” says Mr Lomer. “Proper planning for post-deal integration is key to the completion of a successful merger and maximising value.”