The fourth wave in industry, known as Industry 4.0, is underway connecting the physical world to the digital. To bring these together, manufacturers are developing smarter, better-connected machines that use big data, machine-to-machine communication and machine-learning technology to optimise productivity.

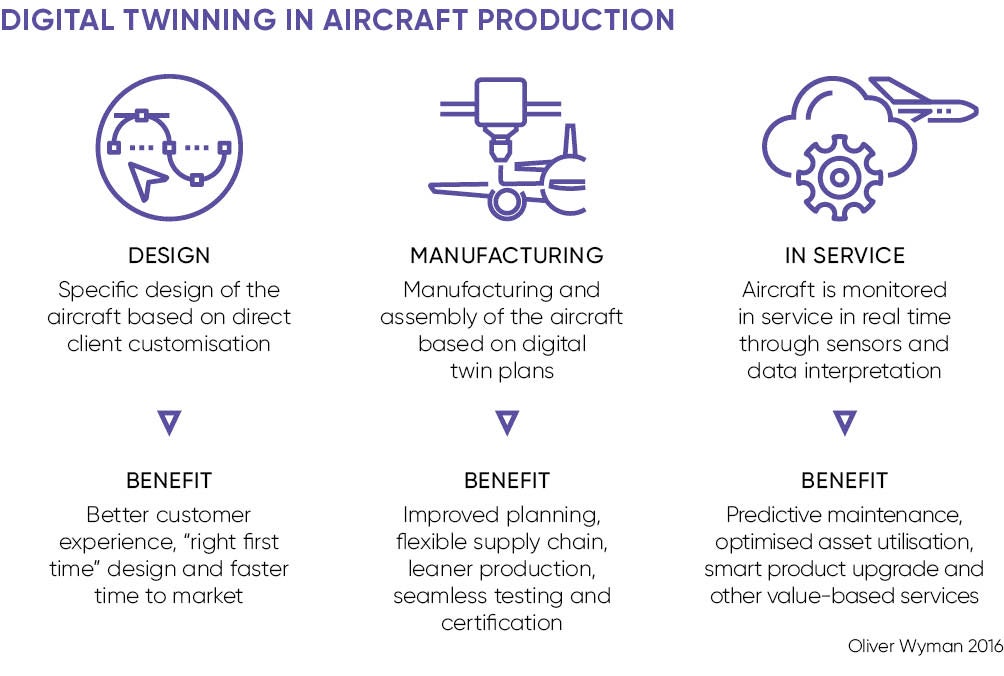

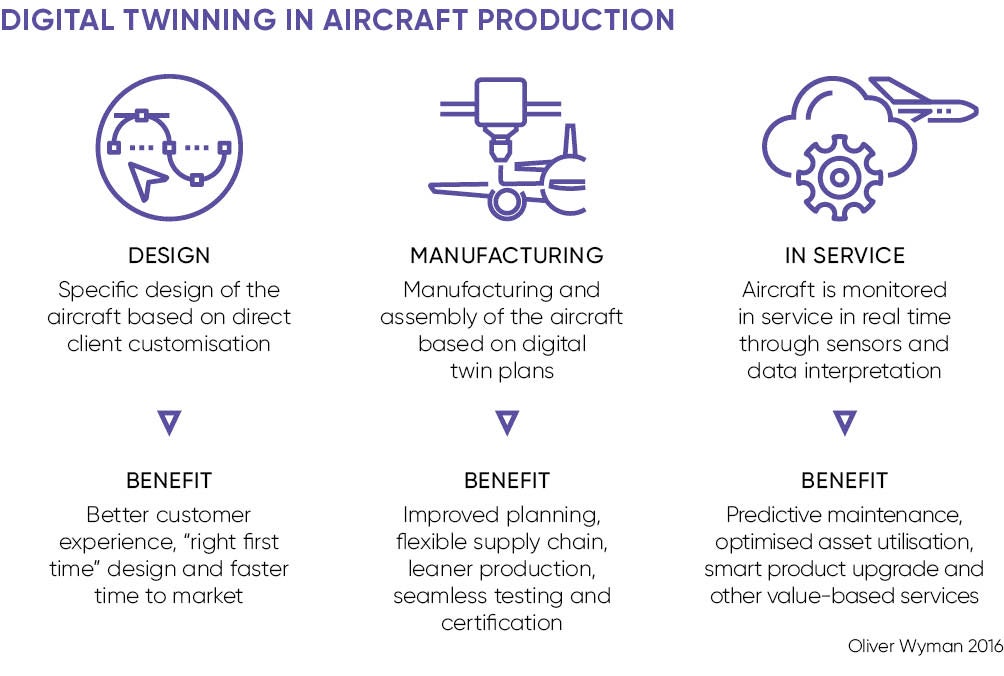

Digital twinning, the mapping of a physical asset to a digital platform, is one of the latest technologies to emerge from Industry 4.0. It uses data from sensors on the physical asset to analyse its efficiency, condition and real-time status. Up to 85 per cent of internet of things platforms will contain some form of this by 2020, according to Orbis Research.

Data collected by digital twins are predicting breakages before they happen and reporting them to human operators to save money and time during production. Before the faults occur, businesses can order parts from companies that source automation components, reducing the risk of downtime caused by broken machinery.

“Historically, designers had little opportunity to test and amend their prototypes,” says Jonathan Wilkins, marketing director at EU Automation, an industrial automation firm. “But digital twinning allows manufacturers to edit a virtual prototype throughout the production process. This model reduces development time and costs as the final construction improves efficiency after analysing simulations.”

Industry impact

Many industries are beginning to adopt the digital twin approach for product design, including construction, and asset management of buildings and infrastructure. The £15-billion Crossrail project, for example, has a digital twin model of the whole network.

Digital twins used to assist in long-term asset management are in their relative infancy, but are likely to reduce the running costs of infrastructure to provide substantial savings over the operating life of built assets.

“By involving many more design, manufacturing and asset management parties to collaborate at a much earlier stage than usual, the use of digital twins has cut the cost of delivering capital built assets by around 20 per cent over the last five years,” says Professor Tim Broyd, president of the Institution of Civil Engineers.

American conglomerate General Electric relies on digital twinning to build and maintain its wind farms. Virtual models allow engineers to monitor and control the turbines, identifying problems before they occur. An energy forecasting application in the virtual plant integrates with the twins and predicts the power outputs.

“Twins are an excellent way to digitise the physical world for an industrial company,” says Deborah Sherry, chief commercial officer at GE Digital, the industrial internet division of General Electric. “They are asset centric, which is a very natural way for industrial enterprises to think about their world. The twin pattern offers a framework for assembling the many individual elements of digitalisation into a coherent whole.”

Oil and gas giant BP is developing digital twins that are model representations of physical projects like new oil fields. Digital twinning helps BP’s engineers to visualise their projects and virtually simulate actions before executing on physical assets.

By sharing the digital representation with multiple engineering partners, different perspectives are considered to reduce risks and oversights. Digital twins also allow BP to create a digital model of an asset before investing in its construction.

“Once our engineers trust the digital representation of the physical asset, the digital twin can be used to plan and manage the asset to ensure that it runs as efficiently as possible,” says Ahmed Hashmi, BP’s global head of upstream technology.

At BP’s gas collection facility in Alaska, for example, a digital twin visualises thousands of pipes and connections to plan maintenance, identify equipment for decommissioning and perform planning for equipment installation. “This can all be carried out from the safety of an office, which is particularly important as the facility is regularly covered beneath snow,” says Mr Hashmi.

Changing business models

Digital twinning is not only changing product life cycles and the skills required of staff. In many cases it’s influencing the business models of large, established companies, in particular driving them to stop selling products and start selling services.

Twins are an excellent way to digitise the physical world for an industrial company

Aggreko and Rolls-Royce, for example, now sell power instead of power generators or aero engines. This is only possible because of the extra insights that digital twinning provide into exactly what’s going on in those products.

The technologies required to extract data from an asset or product are readily accessible, such as using computer-aided design 3D models to overlay the physical and operating data generated from the sensors. The digital twin combines real-time data and predictive data from existing software products.

Another important element is the technology required to visualise the information that comes from the digital twin. The majority of applications use virtual or augmented reality innovation for this, such as Microsoft HoloLens or stereoscopic 3D projectors.

The Advanced Forming Research Centre in Glasgow has been using digital twins in the design process of a project aimed at improving the filling of casks for the whisky industry. The research centre is saving materials and time by designing a digital prototyping system rather than a physical one it knows it will have to remake.

“Often designs would be scaled back to ensure function and manufacturability,” says Danny MacMahon, the centre’s head of metrology and digital manufacturing. “With a digital twin, this can be tested as part of the design stage and therefore removes the constraints that traditional product design created.”

As organisations continue to use fewer physical prototypes, they will create better products and reach the go-to-market phase faster. This not only makes the full life cycle of a product more efficient and cost effective for large enterprises, but also reduces the barriers to entry for smaller companies, creating new jobs and business opportunities.

Industry impact