If retail really is theatre, then no one puts on a show quite like a high-end store. Given that a cardboard box on the doorstep can’t really compete with the luxury boutique experience – all exquisitely tasteful displays and courteously attentive staff walking the marble floors – it’s hardly surprising that luxury brands were initially sceptical about ecommerce.

Established in London in 1934, Ettinger is a manufacturer of fine leather goods. The firm started its etail operations in 2009. Its chairman and CEO, Robert Ettinger, recalls that “we – like many other luxury brands – weren’t sure at first whether we should have a website. Back then, it was considered wrong to sell luxury online, because luxury was also very much about the personal experience. Many of us resisted for a few years, because we were all concerned about the damage that going online might do the brand. But then we started seeing luxury brands opening their ecommerce websites one by one, so we felt we needed to try it too.”

Amazon is great at what it does but it’s seen very much ‘pile it high, sell it cheap’ and our sector is all about exclusivity and protecting the brand image

Not every luxury brand has had such qualms. Champagne Boizel – a business that’s exactly one century older than Ettinger – was an early adopter of ecommerce by anyone’s standards. It opened its online store in 1997, becoming the first champagne house to take the plunge.

“The challenge then was to convince customers to buy online, which felt insecure at the time,” recalls its CEO, Florent Roques-Boizel. “Ecommerce has grown for us in recent years and then the pandemic had a big effect on sales through this channel. They increased by more than 50% in 2020.”

And, just over two decades ago, Net-a-Porter proved that the luxury sector could not only do ecommerce, but also do it very well. The company’s president, Alison Loehnis, says: “We’ve always worked on the idea that we bring the store to you, wherever you are in the world, on your terms and whenever you need it.”

The previous time this traditionally staid sector had experienced such disruption was in the late 1980s, with the emergence of the luxury conglomerates LVMH, Kering and Richemont, which owns what is now known as YOOX Net-a-Porter Group. Today these behemoths, which have swallowed several long-established luxury houses, are putting their considerable weight behind an ecommerce revolution. Alongside them is Farfetch, which has used cutting-edge tech to increase its sales by 46% in the first quarter of 2021.

China, whose consumers will spend £178bn a year on luxury goods by 2025, according to McKinsey, is driving much of the sector’s growth – and collaboration – in ecommerce. In November 2020, for instance, Richemont and Alibaba announced that they were jointly investing £780m in Farfetch to develop the Chinese market.

Kering, meanwhile, has increased its stake in Farfetch by £35m through its investment vehicle, Groupe Artémis. This move may lead to a connection between two of the biggest luxury ecommerce platforms – Farfetch and YOOX Net-a-Porter – that could give them Amazon-level dominance in their sector.

For its part, Amazon is launching Luxury Stores. But, despite the offer of specially created storefronts and additional controls for luxury brands, the concept has attracted little enthusiasm from them so far. LVMH, for instance, has already declared that it will not get involved.

As a senior manager at one luxury brand says: “Amazon is great at what it does, but it’s seen very much as ‘pile it high; sell it cheap’, while our sector is all about exclusivity and protecting the brand image.”

The biggest etail challenge for most luxury brands is to align their prices online with those in physical stores, observes Luca Solca, MD, luxury goods, at Bernstein Research in Switzerland.

“The risk is not the brands directly offering lower prices online for their products. Rather, it is the brands’ wholesale customers,” he explains. “This is the reason you saw such a significant reduction in wholesale exposure, with brands such as Gucci, Prada, Burberry and Dolce & Gabbana cutting their wholesale.”

Luxury shoemaker Crockett & Jones is well aware of this factor, says its ecommerce and marketing director, James Fox. “We don’t want to enter a discounting war by discounting products to entice a customer to a website,” he stresses. “This would have a negative impact on our reputation. We work hard on not becoming another discount brand.”

Fox continues: “Embracing ecommerce draws us, and other companies, into a faster-paced sales environment all around the world. It’s harder to control – and at Crockett & Jones we have a very strong pricing strategy.”

It was considered wrong to sell luxury online, because luxury was also very much about the personal experience

Pricing issues aside, maintaining the luxury experience is essential for brands as they develop their etail operations.

Loehnis explains: “At Net-a-Porter’s high-tech distribution centre, a crane selects your product and puts it on a conveyor belt without a human in sight. But then your product is painstakingly wrapped by hand and tied with a ribbon. That combination of analogue and digital works really well for the luxury sector. Technology provides speed and precision, but it must allow for a human to add that personal touch.”

She adds Net-a-Porter gives “extremely important people” – the 3% of its customers who account for 40% of its revenue – access to new products before anyone else. It also offers them style consultations and a personal shopping service.

Traditional British menswear brands have tended to find ecommerce a challenge, but they’re working hard to move with the times. Your tailor may not be present in person to measure you up, but there are now online alternatives to that experience.

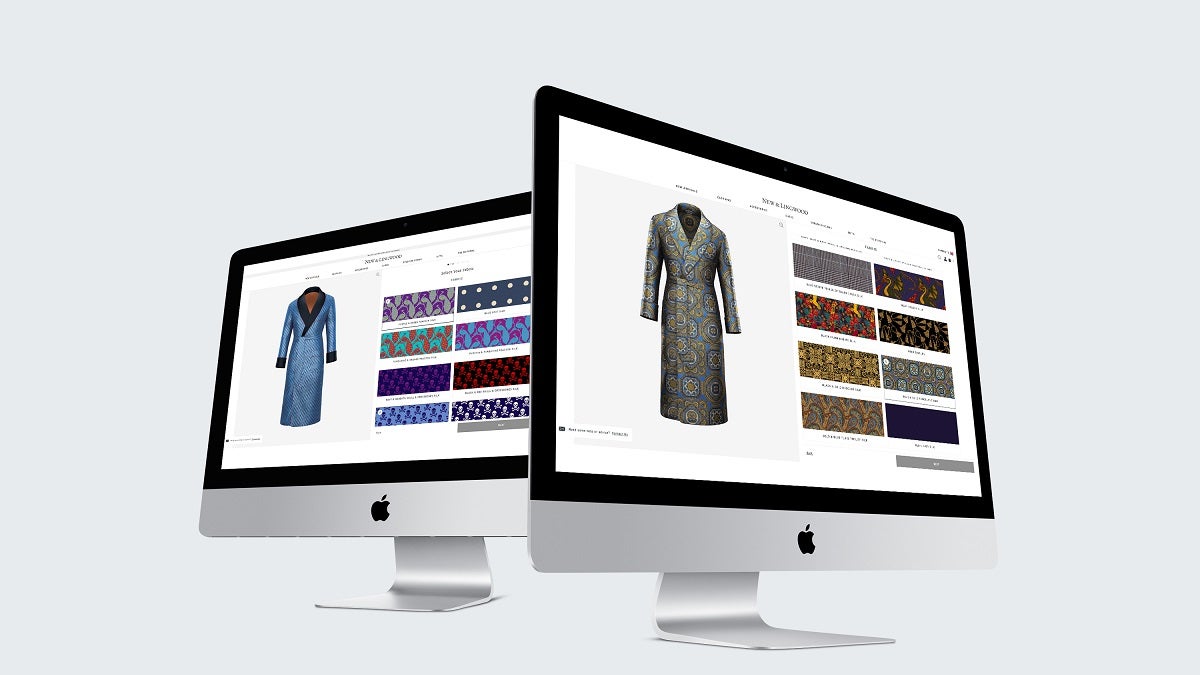

Freddie Briance is CEO at New & Lingwood, a gentlemen’s outfitter that’s been in business since 1865. “The challenge for us has been to build our expertise rapidly in digital while making the significant changes to our product mix and operational model that enable us to be successful online,” he says. “For us, personalisation is central to the luxury experience. Last year we started offering a digital service that allows our customers to design a custom dressing gown from our broad selection of silks. Based on the very positive response to that, we will be expanding this service into other categories this year.”

Luxury brands are even starting to use advanced technologies to engage with younger, digital-native consumers. Lelio Gavazza, executive VP of sales and retail at Bulgari, explains: “Gen Z loves technology but also craves interactions. At the end of 2019 we started offering a ‘virtual try-on’ facility, enabling customers to see our creations in augmented reality. They can personalise selected jewellery and accessories with letters and symbols, for instance, and see the preview in AR. Our group gifting service, with personalised video messages, is also much appreciated by the younger generation.”

Done well, ecommerce is not merely another sales channel; it’s a way of engaging more deeply with customers, curating collections, tailoring products and enhancing customer service – which is very much what luxury has always been about.

“There’s so much more to do,” Loehnis says. “Technology opens up so many opportunities to make the whole luxury experience even better.”

If retail really is theatre, then no one puts on a show quite like a high-end store. Given that a cardboard box on the doorstep can’t really compete with the luxury boutique experience – all exquisitely tasteful displays and courteously attentive staff walking the marble floors – it’s hardly surprising that luxury brands were initially sceptical about ecommerce.

Established in London in 1934, Ettinger is a manufacturer of fine leather goods. The firm started its etail operations in 2009. Its chairman and CEO, Robert Ettinger, recalls that “we – like many other luxury brands – weren’t sure at first whether we should have a website. Back then, it was considered wrong to sell luxury online, because luxury was also very much about the personal experience. Many of us resisted for a few years, because we were all concerned about the damage that going online might do the brand. But then we started seeing luxury brands opening their ecommerce websites one by one, so we felt we needed to try it too.”

Amazon is great at what it does but it’s seen very much ‘pile it high, sell it cheap’ and our sector is all about exclusivity and protecting the brand image