Innovation is not a word readily paired with the antiquated, Dickenson perception that many have of traditional law firms. But it has become one of the latest buzzwords within firms themselves.

Jeff Wright, director of transformation and operational change at UK law firm TLT, says innovation is “board mandated and directed” with “development and evolution front and centre for law firm strategies”.

Driven by shifting client demands for better value for money and greater price certainty, and significant changes in the legal landscape bringing competition from new players moving into the market, employing new business structures and funding mechanisms, firms have been forced to innovate.

Their initial response came in the form of legal process outsourcing, so-called off-shoring or north-shoring, more flexible working practices and alternative fee arrangements.

But advances in technology are quickening the rate of change and have forced law firms to get to grips with a novel and rapidly expanding techie lexicon – artificial intelligence (AI), blockchain and machine-learning, and systems with equally alien-sounding names, such as RAVN, Kira, Neota Logic and Purple Frog.

Many firms are investing in AI systems to carry out contract and document review, e-discovery and due diligence in a fraction of the time it takes junior lawyers or paralegals, and the smart machines do not get tired, require lunch breaks or take time off.

Next steps

The “next frontier”, says Paul Lewis, capital markets partner at international firm Linklaters, is using natural language processing to carry out legal research.

The changes bring with them a growing range of unlawyerlike job titles, often belonging to employees with non-legal backgrounds who bring with them their experience from sectors more technologically advanced; meet the business analysts and transformation directors.

Mr Lewis is one of three partners on Linklaters’ innovation steering group tasked with helping to drive change across the firm. They are looking at the skills required by lawyers of the future and piloting a course teaching 40 of its staff, including lawyers, how to code.

It is also developing an Ideas Pathway to encourage staff to come up with innovative ideas that will be evaluated and could be employed to increase efficiency.

I don’t subscribe to the notion that lawyers will be replaced by robots, but lawyers will be augmented by machines

As part of its innovation programme to reimagine the business of law, Baker McKenzie has instituted an innovation committee which reports to the firm’s executive committee.

Jason Marty, Baker McKenzie global operations director, explains that as part of its innovation framework, the firm is employing “design thinking” to “reimage the existing service we provide and break it down to look at it from the perspective of the client’s needs, with technology as a key component”.

Some firms are starting to use innovation as a key performance indicator (KPI) to help them target resources on initiatives that make a strategic difference. The challenge in doing so, says TLT’s Mr Wright, is to “come up with a KPI that is relevant and measurable”. TLT decided not to proceed.

Adapting to change

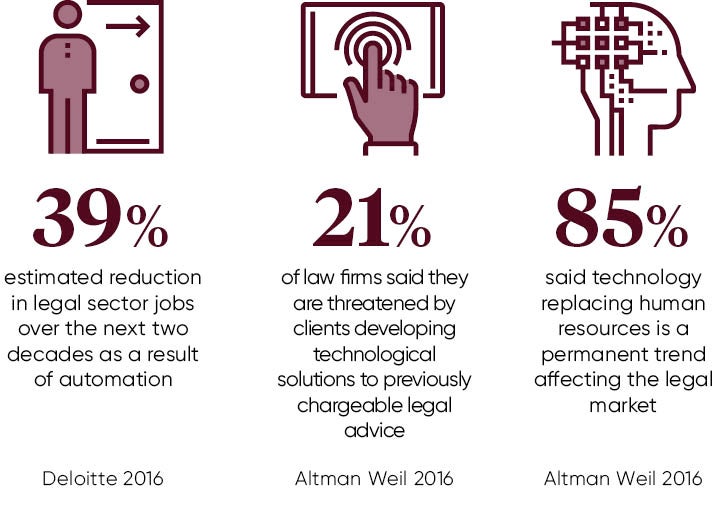

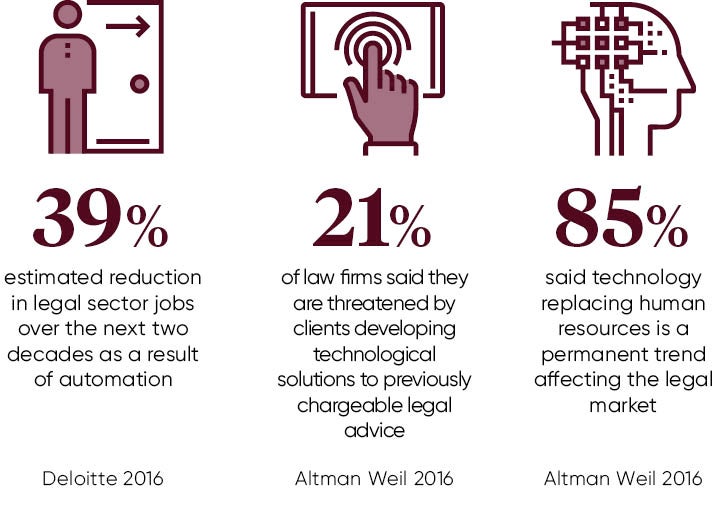

All of this change, says a report from Deloitte, means the legal profession will look radically different in the future. Developing legal talent: Stepping into the future law firm says technology has already contributed to a reduction of around 31,000 jobs and predicts automation will cut legal sector jobs by 39 per cent (around 114,000) over the next two decades.

All is not doom and gloom. The same report suggests the legal sector is growing and, while there may be fewer traditional lawyers, it predicts a bright future for elite lawyers who will possess a new mix of skills.

Dismissing suggestions that lawyers may innovate themselves out of work, Mr Wright insists clients will always want a lawyer’s human touch.

Mr Lewis concurs: “I don’t subscribe to the notion that lawyers will be replaced by robots, but lawyers will be augmented by machines. It will change how law firms operate and you will no longer have so many humans doing the more repetitive and mundane, but essential, tasks.”

Which, adds Mr Wright, raises the question of how to maintain the future pipeline of talent if the traditional work of junior lawyers becomes increasingly automated.

In recognition of the crucial and ever-expanding role of technology in law, Ulster University launched the UK’s first Legal Innovation Centre, designed to operate at the intersection between legal process innovation, technology, education and access to justice.

The Centre, which opened in February, is a collaboration between the School of Law and the School of Computing and Intelligent Systems. It has received financial backing from Invest Northern Ireland and global law firms Allen & Overy and Baker McKenzie, both of which have established legal support centres in Belfast.

Centre director Catrina Denvir says it aims to teach students and professionals about the technological transformation of legal practice, including AI applications, natural language processing and blockchain, and to equip them with the skills to be employable in the tech-driven legal market.

It will collaborate with the industry to bring new applications to fruition and carry out research to understand the implications and benefits that arise from innovation, to facilitate legal process improvement and promote greater economic efficiency.

Another crucial aspect, says Dr Denvir, is to examine how technology can increase access to justice and public engagement with the law. The Visual Law project brings together the university’s law students, legal advice clinic and art students to develop more understandable public legal education information centred on visual, rather than text-based, material.

Dr Denvir says the centre’s focus is not only on technology but also the pursuit of improvement. She adds: “We apply a design-thinking approach which recognises that technology is only one potential solution to problems. There are other solutions that may not require technology at all or for which technology may be ill-suited.”

Next steps