CEO activism can be a double-edged sword, but chief executives are increasingly recognising the value of taking a stance on key societal issues, not least in terms of employee engagement.

Although adopting a public position on important matters is still not widespread, it is set to become more commonplace over the next few years and for good reason. According to research and advisory firm Gartner, 87 per cent of staff now expect senior executives to make a public stand on issues that are relevant to the business, while just under three-quarters believe the same should be true even for unrelated matters.

The biggest push in this direction is coming from millennials and Generation-Z workers, many of whom are not only socially active and vocal themselves, but will also make up the single biggest segment of the workforce over the next five years, which means the subject is not going to go away.

As a result, those senior leaders who fail to don the CEO activism mantle around issues of their own choosing risk being overtaken by events and facing pressure to act. This means the issue will choose them instead, warns Michael Barrington-Hibbert, founder of executive search and advisory firm Barrington Hibbert Associates.

But there are other drivers behind the growing desire of some leaders to get involved in CEO activism. These consist of a pragmatic mix of altruism, which has been catalysed in some instances by the human tragedy caused by the coronavirus pandemic, and recognition of the commercial appeal of businesses taking a purpose-led approach.

Dave Vann, managing director of strategy and creative agency ABA, explains: “It’s partly driven by a desire to serve society, but there’s also the view that by doing so, employees will be more motivated and work harder for you, which affects the bottom line. It also appeals to customers, which means it can help increase market share too.”

Boosting employee engagement

Put another way, says Matt Gitsham, associate professor and director of the Ashridge Centre for Business and Sustainability at Hult International Business School, there is “much evidence that those organisations trying to do something positive can have an equally positive effect on employee motivation and morale”.

On the downside though, if leaders get it wrong, they can do serious damage not only to employee engagement, but also to the company’s wider brand and reputation.

It’s partly driven by a desire to serve society, but there’s also the view that by doing so, employees will be more motivated and work harder for you

“If a particular stance seems opportunistic or as if someone’s jumping on the bandwagon, it can feel jarring and will be considered insincere and cynical,” Gitsham explains. “So it’s a really good thing if done in the right way, but it’s pretty negative if not.”

It is this fear of sipping at a poisoned chalice that puts many senior executives off from going down this route in the first place. While the acceptability of sticking their heads above the parapet is more widely recognised than in the past, few have benefited from the leadership development training necessary to prepare them for speaking out publicly in ways that avoid potential misinterpretation and subsequent attack, particularly in polarised societies, such as the UK and America.

But, as Gitsham points out, leaders are essentially damned if they do and damned if they don’t. “While you need to be aware of the risks to the brand, you also need to balance it against the risk of not saying anything at all, as both approaches will inevitably upset someone,” he says.

As a result, not only is it beneficial to obtain professional guidance, but it is also advisable for senior executives to support only those issues that chime with their own beliefs and values, although ideally they should connect with the core purpose of the business too.

The importance of taking action

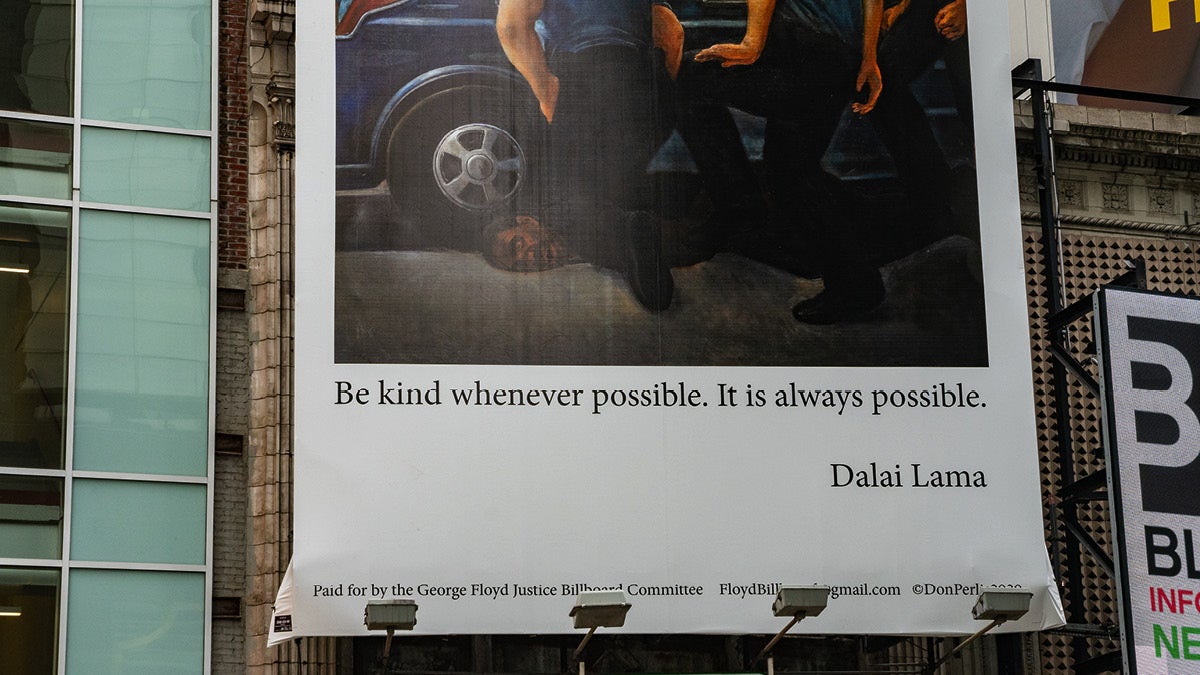

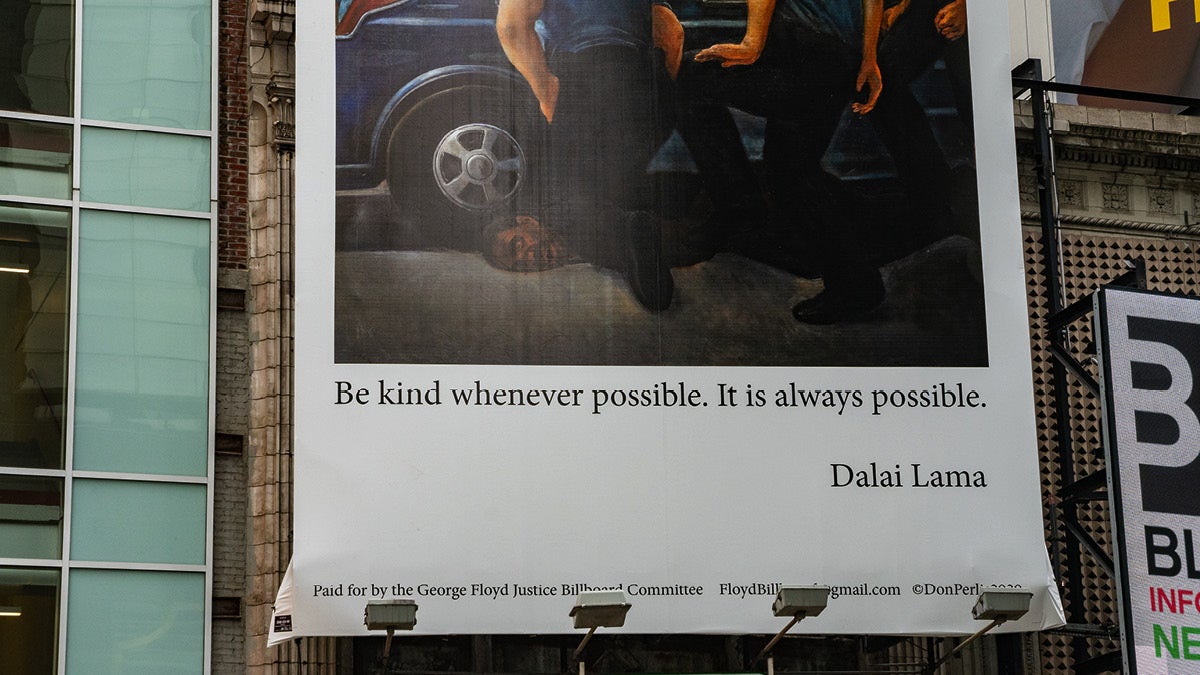

“The crucial thing is that you believe in it, as taking a stance will only work if it’s meaningful, authentic and aligns with what you’re doing in the organisation,” says Gitsham. “So if you speak out against institutional racism and can talk about what you’re doing to tackle it internally, it’s much more powerful and convincing than if you’ve never done anything about it before.”

In the case of a sudden epiphany though, public statements must also go hand in hand with a meaningful programme of work to follow through and effect change, he adds.

Interestingly, the importance of taking action is also reflected in Gartner’s research. It reveals that if business leaders simply make a public statement on a given topic without doing anything, staff satisfaction rates fall by 38 per cent as cynicism and disillusion set in. If words are backed up with appropriate activities though, engagement leaps by 60 per cent.

Another consideration when trying to get CEO activism right is discussing the reality on the ground with a range of stakeholder groups, which includes employees. This involves canvassing opinions on various topics, but it also means “doing the groundwork, finding the gaps and blind spots, and understanding what’s going on” in the organisation day to day, says Vann.

This kind of approach not only boosts individual credibility and prevents basic errors, but also helps create a wider feeling of shared purpose and values internally and externally, which again boosts engagement.

“You don’t want your brand to be wholly wrapped up in, and dependent on, the CEO. The issue also needs to be accepted as part of the organisational culture so other people can own it in their own way too. But if the CEO can infect others with their passion, that’s where it becomes really powerful,” Vann concludes.

CEO activism can be a double-edged sword, but chief executives are increasingly recognising the value of taking a stance on key societal issues, not least in terms of employee engagement.

Although adopting a public position on important matters is still not widespread, it is set to become more commonplace over the next few years and for good reason. According to research and advisory firm Gartner, 87 per cent of staff now expect senior executives to make a public stand on issues that are relevant to the business, while just under three-quarters believe the same should be true even for unrelated matters.

The biggest push in this direction is coming from millennials and Generation-Z workers, many of whom are not only socially active and vocal themselves, but will also make up the single biggest segment of the workforce over the next five years, which means the subject is not going to go away.