Sovani James dreamed of a long and fulfilling career in law, and she took a major step when she became a junior lawyer with a major firm with offices in London and across the South East.

But her dream became a nightmare as she struggled to cope with a culture of fear in her workplace, which has been criticised by the Solicitors Disciplinary Tribunal.

In January, Ms James was found to have acted dishonestly in creating and backdating letters to give the impression that a clinical negligence case was progressing. However, the tribunal opted against striking her off the roll after concluding her primary motivation was fear of the consequences from the firm’s management of the discovery of her wrongdoing.

In its judgment the tribunal said: “Pressures suffered by management were passed down to the fee-earning team, who must have felt that they were carrying the weight of the world on their junior shoulders.”

Giving evidence, Ms James said: “Almost daily I would be in tears due to the pressures I was under… The stress I was under was obvious towards the end of my time with the firm. I was clearly distressed and cried regularly. My hair started to fall out and I put on weight.”

Mental health in the workplace is under greater scrutiny than ever and law firms are having to ask tough questions about a corporate culture that promises financial rewards but, too often, at a high personal cost to employees.

In recent years, high-profile suicides of senior partners have made headlines. But the disciplinary process against Ms James, a junior lawyer, shined a light on an unsustainable, target-driven culture that encouraged bullying and intimidation.

Sadly, her testimony will strike a chord with many working in the legal profession. LawCare, a charity set up to support mental health and wellbeing in the legal community, has seen a strong increase in the number of callers to its helpline over the past couple of years.

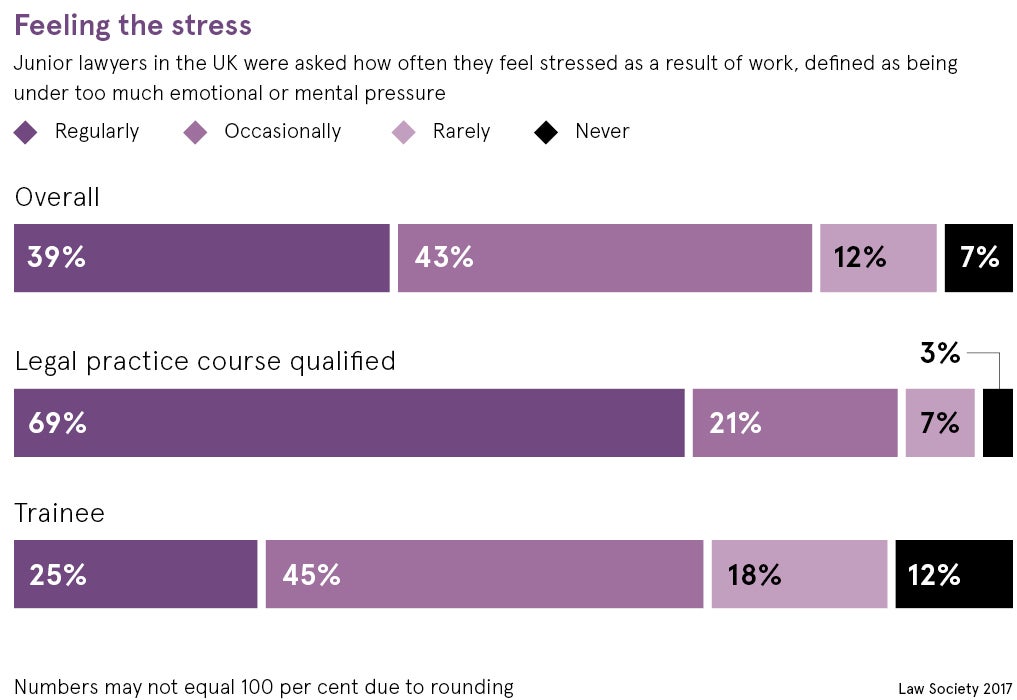

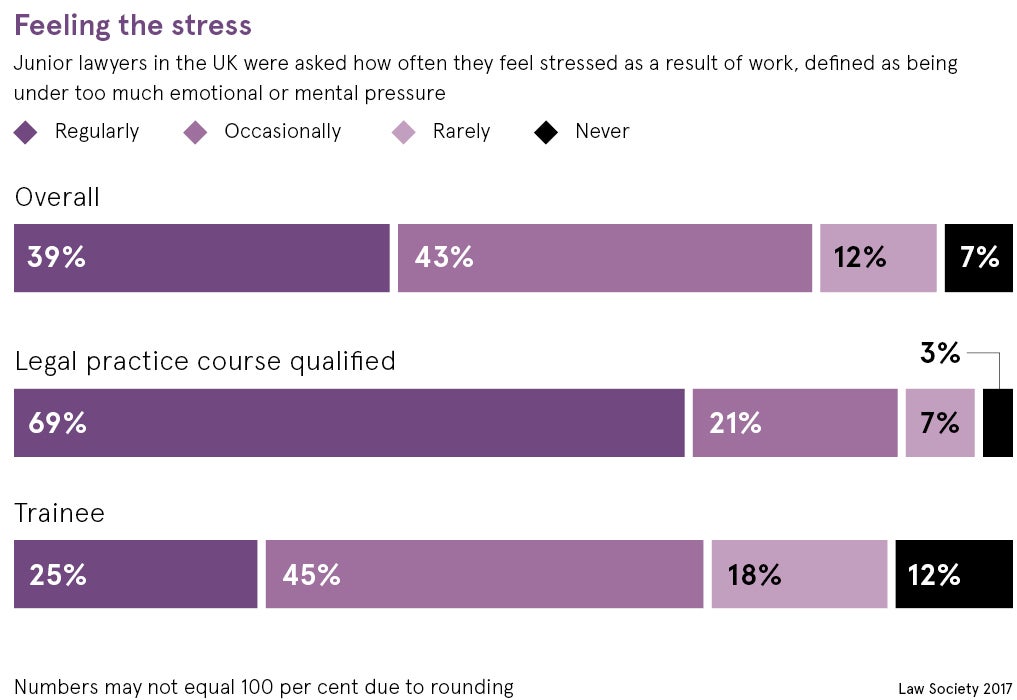

Nearly half the solicitors and barristers who called for help cited depression, anxiety and workplace stress as the reason. The majority of callers were women (65 per cent) and 45 per cent were trainees or had been qualified five years or less. Last year the number of callers rose by 11 per cent over the previous 12 months.

Elizabeth Rimmer, chief executive of LawCare, says the increase in demand for the charity’s support is a cause for concern, but adds that it may also signal a positive change in the culture of law firms.

“Law firms are beginning to take employee mental health and wellbeing seriously. There is a greater awareness that there are issues that need to be addressed. Mental health is higher up the agenda and organisations are understanding that not only is it the right thing to do, but also there is a business case,” she says.

The stigma of mental health remains a huge challenge across the legal profession and not only in the UK. Lawyers and their teams are expected to cope under huge pressure, working long hours with little respite. Under such conditions, it becomes difficult to admit that you are struggling to cope and need help, often with catastrophic consequences.

A study of US lawyers, published by the American Society of Addiction Medicine, found alarming rates of behavioural health problems. Some 28 per cent experienced symptoms of depression, 19 per cent anxiety and 23 per cent stress; 21 per cent screened positive for hazardous, harmful and potentially alcohol-dependent drinking.

Although there is limited equivalent UK data, Ms Rimmer, a former lawyer, says that such statistics are a close reflection of the legal environment here. “Many of the qualities that motivate people to choose a career in the law possibly make them more susceptible to mental health issues,” she says. “Lawyers are high achievers and perfectionists. They have a fear of making mistakes because so much is at stake. They are committed to solving other people’s problems and often do not make time to solve their own.”

Having leaders willing to speak publicly about stress and depression is having a positive impact in the legal profession. Nigel Jones is chair of the City Mental Health Alliance, a coalition of organisations that have come together to create an environment where mental health is discussed in the same way as physical health. He is also a senior partner at the law firm Linklaters and a specialist in intellectual property.

“We created the City Mental Health Alliance five years ago to make the City of London a healthier place to work,” says Mr Jones. “We’re doing this by trying to reduce the stigma and improve the literacy around mental health, and identify practical steps that businesses based in the City of London, primarily larger businesses, can take to help people remain well.”

Despite the challenges, LawCare’s Ms Rimmer is optimistic about the outlook for mental health in law firms. The Solicitors Disciplinary Tribunal’s strong condemnation of working practices, in the Sovani James case, is just one sign that attitudes are changing for the better.

“Employers are realising they need to provide more flexible working opportunities and that they need to trust their staff,” she says. “The current generation is less attracted by high salaries and more interested in a better work-life balance.”

As for Ms James, she has been able to continue her career with a different firm in Chester, while living closer to her family home.