When Uber acquired Otto, a self-driving car startup in 2016, it thought it was hiring some of the industry’s smartest engineers; what Uber also purchased was a lesson on the importance of intellectual property (IP).

Otto’s founder Anthony Levandowski, a former engineer at Alphabet’s autonomous vehicle unit Waymo, had downloaded a trove of files from Waymo before he left the business to set up Otto.

In the rush to complete the acquisition, Uber failed to investigate questions about Otto’s IP that were raised during the due diligence process, dragging the ride-hailing company into a trade-secrets row that ended with it agreeing to pay $245 million in Uber shares to Waymo to settle the case.

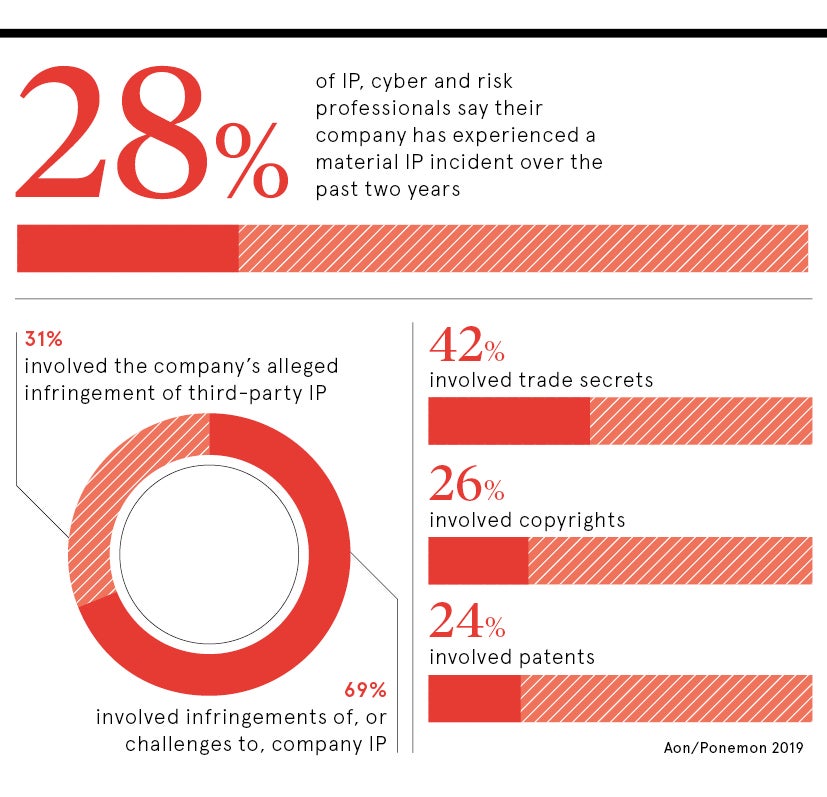

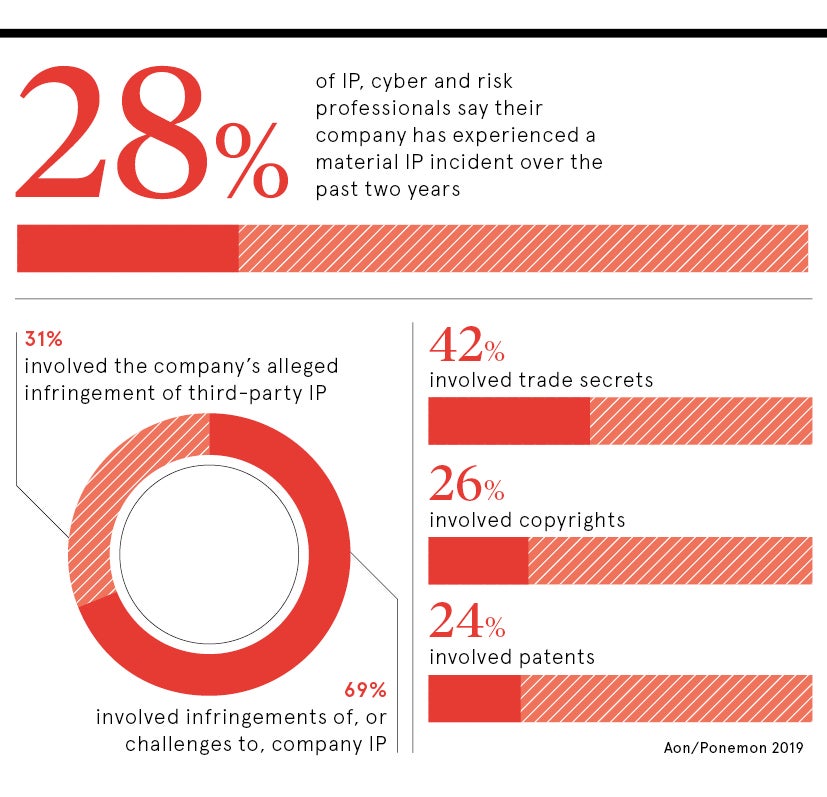

While Uber says it didn’t receive or use any of Waymo’s trade secrets, the dispute underscores how companies that don’t take the importance of IP seriously could end up facing a business disaster. As the Waymo settlement also showed, protecting trade secrets is a valuable enterprise, but it is one that is often overlooked by business leaders.

“There are not many companies that do have a solid trade-secrets programme in place; even if they know they have something, they lack the skills and knowledge of how to protect it,” says Tilman Breitenstein, group leader for IP at BASF. “Startups and smaller companies often have a higher fluctuation of staff and that makes it much more difficult for those businesses to protect their trade secrets. They also need to attract investors, which means going out and talking about their business, which also puts them at higher risk.”

The need to consider trade secrets as part of a wider IP strategy is not the only IP asset companies might overlook or undervalue.

“Sometimes an IP strategy is just thought of as a patent strategy, but it’s much more than that. It includes the correct use of software licences, it includes confidentiality, it includes trademarks and branding; there are a whole range of things companies need to get right to avoid something going wrong,” says Maria Anassutzi, lead European IP counsel at Canon.

Preventing a business disaster

One common mistake companies make when failing to recognise the importance of IP is not aligning their IP strategy with their overall business strategy.

“Things move much more quickly these days, so you might have a great strategy for your domestic market, but if you want to expand into another market, you could find your trademark has already been taken,” says Katharine Stephens, co-head of lawyers Bird & Bird’s London IP practice.

Apple, for instance, was famously caught out by trademark issues in China. In 2012, it had to pay $60 million to Proview Technology to use the iPad trademark in China after discovering an earlier deal to acquire trademark rights from Proview had not included those registered in China, which were owned by a different part of Proview. Then in 2016 Apple lost a legal battle to stop another Chinese company using the iPhone trademark on leather goods.

Another mistake companies make that could trigger a business disaster is not having a process in place to ensure any IP that is created is promptly protected.

“Companies need a strategy for capturing innovation,” says Mark Aldred, patent attorney at Gill Jennings & Every, an IP law firm. “This could include having a patent-filing strategy or a periodic assessment or check with the inventors and IP advisers to see if there is any new IP being developed and what the best way of protecting it is, rather than doing so on an ad hoc basis and then realising they have already published it and so may not be able to obtain protection.”

In some cases protections can even be removed. In 2018, the European Court of Justice backed an earlier ruling from the European Union’s Intellectual Property Office that the design patent for Crocs, the plastic clogmaker, was invalid because the company had applied for protection two years after it had first unveiled the design at a Florida boat show. This means Crocs can no longer stop anyone copying the shoe’s distinctive design in the EU.

Protecting the bottom line

Some companies, particularly startups and smaller businesses, might also fail to understand the importance of IP because they are preoccupied with being first to market, says Sahira Khwaja, partner at law firm Hogan Lovells.

“IP is seen as complex, confusing and expensive, and something to be dealt with later,” she says. “Unfortunately, not acting early enough to protect IP properly can mean a lost opportunity to prevent competitors from entering the market with a similar product or service. This can have a knock-on effect on the value of the business, making it harder to get funding from investors and even putting off future buyers.”

Yet even companies that have spent time developing their IP strategy are not immune from making mistakes.

“A strategy on its own is not enough,” says Breitenstein. “It’s really about the implementation and execution. I have seen many strategies that have been nicely drafted, but are not executed properly, so it’s really about making deliberate decisions and then executing that; it’s often where companies fail.”

And while companies have always needed to protect their IP, the pace of innovation in many countries around the world means the commercial importance of IP is only going to increase.

“The marketplace is becoming increasingly competitive, so companies now more than ever do need to be looking at protecting and enforcing their intellectual property so they can secure a competitive advantage to build market share and keep competitors out,” Michael Gavey, head of the London IP group at lawyers Simmons & Simmons, concludes.

Preventing a business disaster