Ivy League graduate Andy Moon had the big job, the fat salary and was primed for the house in New York’s Hamptons. But he chose a different tack. Today, the 29-year-old ex-McKinsey consultant helps bring affordable solar electricity to hospitals and schools across rural Nepal.

So a do-gooder? Yes, but with a difference. Instead of joining a charity, Mr Moon opted to deliver on his social mission through his own for-profit company.

“When I launched SunFarmer in 2014, we felt that the best way to accomplish this was by starting locally run solar energy businesses in developing countries,” the young entrepreneur explains.

SunFarmer is part of a new wave of so-called social enterprises that set out to harness market forces for social or environmental good. But why the shift and what hope, if any, is there of the business world following?

Having a sense of purpose is increasingly important to early-career millennials

The trend has a lot to do with generational changes. Having a sense of purpose is increasingly important to early-career millennials. The more ethical their employer, research shows, the longer they will stay.

The surge in socially oriented startups also stems from a belief that the market can deliver where others have failed. Governments and charities have ploughed billions of dollars into worthy causes, but to little effect. For the most part, the poor are still poor and the planet continues to warm.

SunFarmer provides affordable solar energy for healthcare, education, business and agriculture in hard-to-reach areas across the developing world

Business, in contrast, has a suite of different tools at its disposal: innovation, efficiency, persistence, and acute attention to people’s wants and needs. Put these to good use and serious inroads into social and environmental problems can be achieved, advocates of sustainable business say.

“When business uses its awesome power to nurture and restore our society and our planet, then it can become a real force for good,” argues Charmian Love, co-founder of B Lab UK, a charity that verifies mission-minded businesses as “B Corps”.

A tad optimistic, perhaps? Business’s track record for putting people before profits isn’t exactly stellar, after all. Yet the explosive growth of the B Corp movement points to a change in the air. If nothing else, it shows that a more balanced approach is at least feasible.

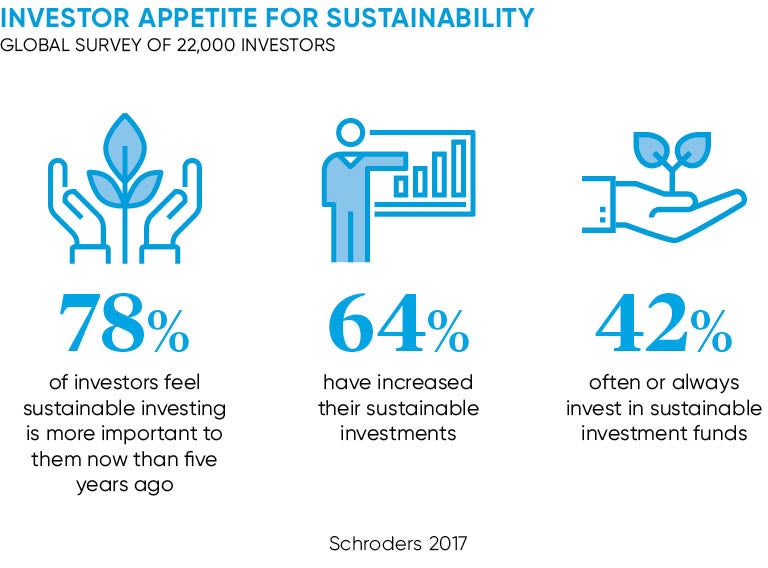

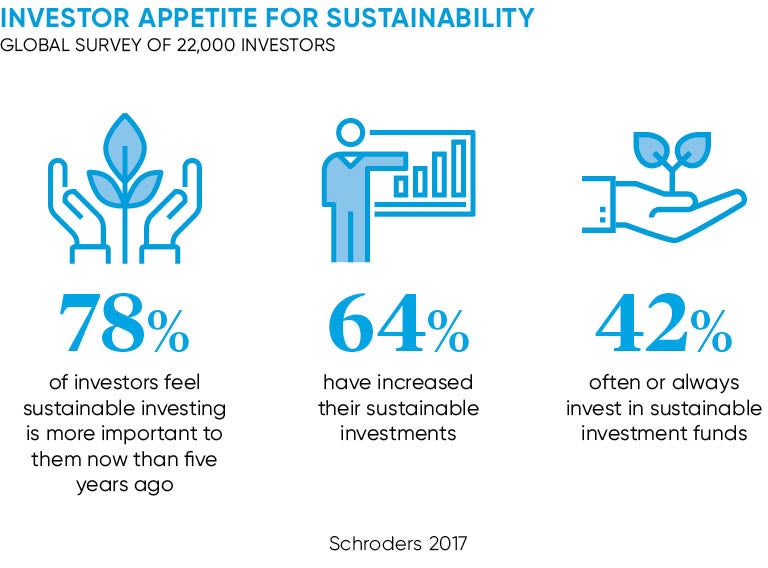

That doesn’t quite cut it though. Big business needs to be convinced that being more sustainable is not just possible, but profitable. Again, the winds of change are blowing. A recent study by global bank Schroders found that investors – a group not known for their bleeding hearts – were motivated to invest in sustainable funds as much for the financial returns as for the societal impacts.

For John Elkington, the business guru behind the influential concept of the triple bottom line – people, planet and profits, together – it all comes down to a question of framing

Take time scales. Imagine if business leaders started looking five or even ten years ahead, rather than just to the next quarter, Mr Elkington conjectures. Suddenly, the fact that the world has less water or fossil fuels cost more takes on a more bottom-line hue.

The same can be said for how companies conceive of abundance, value creation, design, resources and even morals. See these concepts differently and, so the theory goes, today’s headaches become tomorrow’s breakthrough business opportunities.

For B Corps and their ilk, this future-fit agenda is likely to be wired in from the outset, says Mr Elkington. For most large corporations, it is not.

So can big business change its spots? Some are sceptical. Genuine sustainability isn’t about doing a bit more charity work here or introducing an eco-product there. It’s about a root-and-branch reform in what companies do and how they behave.

So says Edward Davies, a recent graduate from London’s Cass Business School and co-founder of Wearth London, a new online retailer selling sustainable products from small UK firms.

“I think it will be very difficult for these large companies to properly adapt as, in the short term, it might conflict with their shareholders’ interests,” Mr Davies says.

Almost all large retailers now have supply chains that stretch across the globe, he adds. The idea of buying oranges grown in Spain or t-shirts made in Mexico presents a “definite contradiction” with shopping in an “eco-conscious way”.

Others are more optimistic. For Tim Heard, co-founder of the Circle of Young Intrapreneurs, a global non-profit movement, large corporations are not beyond learning from today’s ethical upstarts. Yes, these firms may be minnows, but so were the likes of Uber and even Amazon once.

Mr Heard’s confidence lies in the growing cadre of corporate employees who buy into the sustainability agenda. He sees growing potential for these insiders to work with the SunFarmers of this world on shared social and environmental challenges.

“The latter bring proven impactful business models, while the former bring capital to scale these business models,” he says.

Examples are beginning to emerge of just such a collaborative dynamic. Take coffee chain Starbucks, which recently teamed up with the recycling design firm Pentatonic to produce eco-chairs for its stores. Or Brazilian cosmetics giant and B Corp member Natura, which just acquired the ethically vocal Body Shop brand.

Such acquisitions can work both ways. The story of Green & Black’s is cautionary here. First acquired by UK confectionary firm Cadbury in 2005, the plucky fairtrade chocolate brand eventually found itself part of the cut-throat Kraft empire. It is no longer so plucky.

Well managed, however, and such mergers can assist large companies to “accelerate their own adoption of sustainable practices”, according to Andy Milligan, co-founder of consultancy firm The Caffeine Partnership.

He points to Coca-Cola’s 2013 acquisition of game-changing beverage brand Innocent as a positive example. Unilever, widely cited for its sustainability leadership, has also bought up a host of small ethical brands over the years, including the radical ice-cream brand Ben & Jerry’s.

“Sustainable business is not a fad,” Mr Milligan insists. “It is quickly becoming about the fundamentals of doing business for all businesses.”