The UK hopes to invest £600 billion over the next ten years to rekindle a “Victorian spirit” by renewing overcrowded railways, roads and airports, building resilience against climate change and improving digital networks.

It expects half to come from the private sector, yet the political and regulatory climate has turned distinctly chilly towards private financing of infrastructure.

Policy announcements from both the government and opposition are sending negative messages to investors, reflecting public concern about whether private provision of public services represents value for money.

Regulation and public opinion curbing private investment in infrastructure

Some investors are reluctant to invest further in regulated sectors such as water and energy, though not enough so far to threaten the UK’s dominance of Europe’s infrastructure market for private capital, an area it has pioneered since the 1980s. Meanwhile Brexit heightens the UK’s need to remain attractive to investors across the economy.

“The private sector needs to respond to the challenge of restoring public confidence. It needs to demonstrate its commitment and value for money,” says Darryl Murphy, head of infrastructure debt at Aviva Investors, which has more than £5 billion invested in UK infrastructure.

The Labour Party has threatened to renationalise energy, rail and water companies, halt the use of private finance initiative (PFI) contracts and bring some existing schemes back in-house. Opinion polls have shown a large majority in favour of reversing privatisation of utilities.

Chancellor Philip Hammond announced in last autumn’s Budget that he is scrapping PFI, used widely in the past to build hospitals and schools, though he held open the prospect of using other means of private finance for infrastructure projects where “it delivers value and transfers risk”.

Regulators are getting tougher, notably in water, where Ofwat is attempting in the latest five-year regulatory period to curb bills, which have risen 40 per cent in real terms since privatisation, and press companies to fix more leaks, while restraining them from taking on too much debt and paying large dividends.

Whoever invests, UK infrastructure is in dire need of funding

The collapse last year of Carillion, the construction company, in part because of project delays in three substantial UK public-private partnerships, further undermined confidence. The problems of Interserve, another contractor, stem in part from a disastrous venture into energy-from-waste plants.

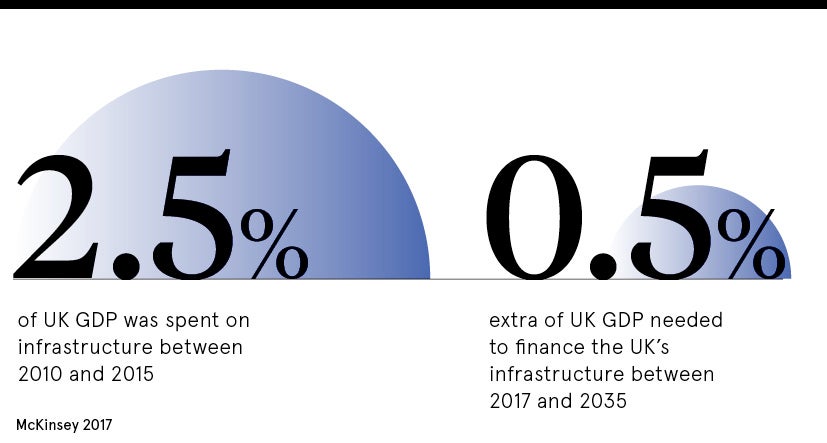

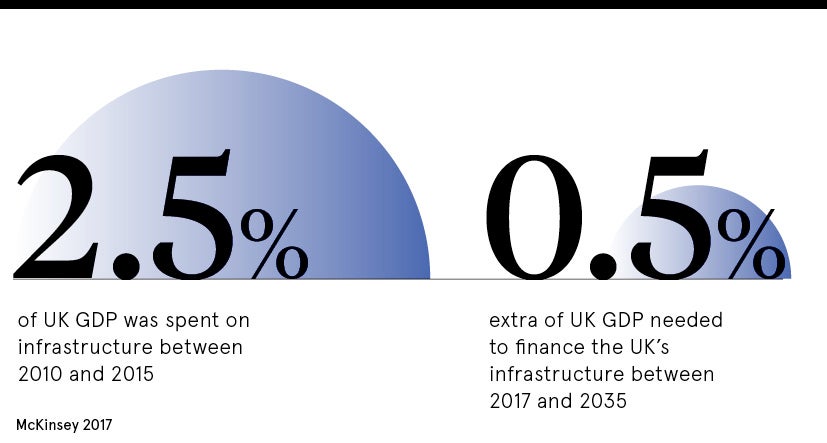

Few doubt the need to renew the UK’s infrastructure. Since the 1980s, the UK has spent less on this than the United States, France, Canada and Switzerland, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Think tank McKinsey Global Institute calculates the UK needs to spend an extra 0.5 per cent of gross domestic product a year until 2035 to meet its needs.

The government is raising its capital spending, but also needs private finance. Private sector projects include the £2.8-billion Hornsea One, the world’s largest offshore windfarm, being built by Danish developer Ørsted off the Yorkshire coast. Heathrow Airport, owned by global investors led by infrastructure specialist Ferrovial, plans to spend £14 billion on a third runway.

Unless utilities are renationalised, much of the planned investment must come from companies in regulated sectors, including energy and telecoms where the cost is met through consumers’ bills. The National Infrastructure Commission is reviewing regulation of the energy, telecom and water industries.

Those who invest their pension in infrastructure are increasingly wary

Infrastructure investors are mostly pension funds, life insurers and sovereign wealth funds looking for long-term investments that provide a steady income stream. They have significant holdings in UK water companies, airports, ports, telecoms, renewable energy and energy distribution.

“There is no question that some investors who have traditionally invested in core infrastructure, the regulated assets, feel the environment is no longer one they want to invest in,” says Andy Rose, chief executive of the Global Infrastructure Investor Association. He insists, though, there is no blanket ban across the sector on investing in the UK.

Mr Murphy points to a surplus of liquidity in the infrastructure debt and equity markets, and relatively limited supply. “Asset prices remain high and borrowers have a wide array of financing options,” he says. Infrastructure remains an attractive asset class in a low interest rate environment for those seeking a premium over government bonds.

Liz Jenkins, partner at law firm Clyde & Co, sees Brexit uncertainty as a problem. “Ministerial time and focus is taken up with this huge issue, and therefore there is not enough focus on infrastructure,” she says. “For investors, you need some certainty and there is nothing but uncertainty currently,” adding that global investors need a consistent pipeline of projects to justify the expense of bidding.

Not clear yet what the viable alternative to private investment is

The Infrastructure Forum, a network of investors, contractors, consultants and other vested parties, complains that only 8 per cent of projects listed in the National Infrastructure and Construction Pipeline are sufficiently certain for contractors to prepare to deliver them.

The Treasury has yet to say what form of public-private partnership it favours after scrapping PFI, which had dwindled to a few projects. Alternatives include the model used for the £4.2-billion super sewer being built under London, which is off the government’s balance sheet, though taxpayers act as a backstop.

Iain Scouller, managing director of investment funds research at broker Stifel, expects some post-PFI mechanism to emerge, but adds: “I suspect the potential returns going forward will be somewhat lower than they were historically.”

Mr Scouller says investors in UK-listed infrastructure funds would like to invest in new projects, but there is nervousness about nationalisation risk. “If they can get returns from infrastructure projects of 5, 6 or 7 per cent per annum, that’s a lot more attractive than very low gilts’ yields,” he says.

Mr Rose concludes that for the private sector to provide £300 billion of investment over ten years, the government must be clearer about the procurement models it will support. But he acknowledges: “The industry needs to have a better narrative about how private finance has delivered benefits for society.”

Regulation and public opinion curbing private investment in infrastructure

Whoever invests, UK infrastructure is in dire need of funding