It used to be private equity firms that owned everything, to quote the title of Jason Kelly’s 2012 book on the trillion-dollar industry. Today there’s a high chance a pension fund also owns the companies that populate our lives from childcare and mobile phone providers to cinemas and funeral parlours.

Difficult returns in public markets have encouraged pension funds to invest in private assets such as infrastructure and property, and private companies provide some of the best returns out there.

Yet investing in funds managed by the likes of private equity titans Blackstone, Apollo or Carlyle can cost a fortune in management and performance fees, known in the business as carry. In 2015 America’s biggest pension fund the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS) revealed it had paid $3.4 billion in performance fees to managers since 1990. Fund investment also restricts investors, or so-called limited partners (LPs), in their ability to control their capital and doesn’t put them on an equal footing with their managers, the general partners (GPs).

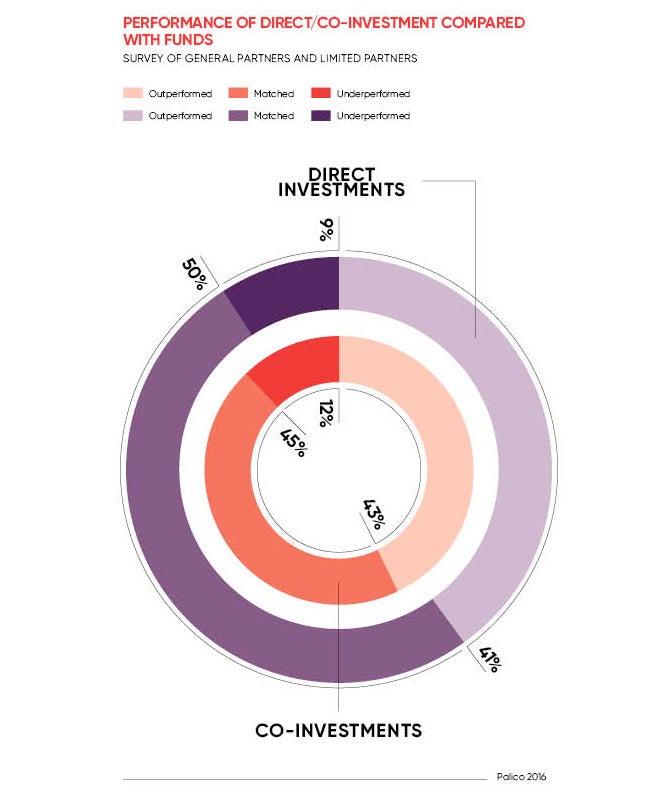

Pension funds have responded in two ways. Most have begun investing in companies alongside the main GP fund in co-investment deals that gives them the freedom to make their own decisions on risk, cuts fees and improves returns. According to a recent survey by data provider Preqin, 68 per cent of investors generate higher returns in co-investments than investing in funds.

“We aim for five to ten co-investments yearly,” says Maurice Wilbrink of PGGM, a Dutch fund which manages money on behalf of a pension fund for nurses and social workers.

But other investors have gone one step further, buying chunky direct stakes in private companies and bypassing GPs altogether. Sovereign wealth funds like Singapore’s GIC and Abu Dhabi’s ADIA have got in on the act.

Among pension funds, it’s the Canadians who have blazed a trail in strategies learnt from the best private equity managers in the world. Like the calculated call by Canada Pension Plan Investment Board (CPPIB), which manages the assets of Canada’s biggest pension fund, to up its investment in China’s e-commerce giant Alibaba. CPPIB invested in the tech company directly and via a commitment to a private equity fund; it then increased its stake again in Alibaba’s blockbuster IPO in 2014.

In co-investments, GPs rather than pension funds still call the shots when it comes to managing investee companies. But when a business is directly owned by a pension fund, it can be a different ball game. GPs have a typical three to four-year investment horizon before they have to realise investors’ returns, but LPs can own a business for years.

“Pension funds don’t have a ticking clock,” says Graham Elton, who leads Bain & Company’s Europe, Middle East and Africa private equity practice. It could mean a gentler journey to improving the business before sale and more deals from business founders that don’t like the more aggressive GP model.

Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, which owns stakes in UK companies such as childcare provider Busy Bees and lottery group Camelot, plays the long game with a distinct edge. It positions itself to scoop up exiting GPs assets, like the majority stake it bought in Kettle crisp maker Shearer’s Snacks when the private equity firm sold out in 2015.

Large internal teams with industry-specific expertise work on value creation to ensure the business grows

It’s an ability to be patient that manifests in other ways too. If investment opportunities are thin on the ground, pension funds can bide their time or invest elsewhere. In contrast, un-deployed capital or “dry powder”, which Preqin currently estimates at $1.3 trillion, burns a hole in GPs’ pockets.

But companies would be wrong to assume that being owned by a Canadian pension fund is an easy ride. Large internal teams with industry-specific expertise work on value creation to ensure the business grows, while proportionate governance rights often include a voice on the board. “It is hard to see the difference between these funds and a GP,” says Ludovic Phalippou, associate professor of finance at Oxford University’s Saïd Business School.

Others are not so hands-on. Singapore’s wealth fund Temasek doesn’t demand corporate restructuring or management changes in its “bottom-up” strategy. Different values from some sovereign funds could manifest in less than responsible investment. “GPs have a reputation and have to be careful of the press. A sovereign wealth fund from the Middle East or China would be less concerned,” says Professor Phalippou.

Competition is increasing as more investors enter the fray. None more so than for the long-term, income-generating asset such as motorway service stations, logistics facilities or elderly housing that pension funds like and are straightforward enough for them to fly solo. It is here in “centre of the fairway deals” that Mr Elton believes traditional private equity funds will soon feel the pinch.

And competition will also drive up asset prices, ultimately limiting the capital gain opportunities available to investors. Competition will also bring down fees, although this hasn’t happened yet since funds are still oversubscribed. Investor demand won’t ease off until the fundraising cycle goes the other way, predicts Mr Elton. “Private equity commitments are driven by exits. GPs will start to feel a slowdown once the money coming out from exits reduces.”

But private equity’s glory days aren’t over yet. Competition promises a shake-up, but even the biggest LPs will always spread risk between funds, co-investment and direct, and small pension funds will stick with their GPs. Besides, where Canadians and sovereign investors have led, many can’t follow. Co-investment isn’t a stepping stone to going direct, says PGGM’s Mr Wilbrink. “The team is not equipped nor has a clear mandate to invest direct.”

The Canadian’s have nurtured world-class deal teams that comb the globe for opportunities. But US and European pension funds have different governance structures with trustees who wouldn’t sanction the cost of retaining top talent with million-dollar salaries.

“It would be very, very difficult to accomplish,” says John Cole, investment director at CalPERS. Internal teams also require scale and many pension funds don’t have large enough private equity allocations to make it worthwhile.

It’s all about ways of investing without the same management and performance fees

They may not be able to do it like the Canadians, but pension funds have other options as well as co-investment, partly as GPs adapt their offering. Managers like Blackstone have created separate accounts for their biggest investors. Held apart from the main fund, these offer many of the benefits of going direct. GPs are also setting up funds which hold on to companies for longer, but offer lower returns.

And in the latest twist, CalPERS is considering buying direct stakes in private equity firms themselves to get a slice of the pie. “It’s all about ways of investing without the same management fee and carry. It’s led to stratification in the private equity market,” Mr Elton concludes.