The lack of diversity in construction is a problem. Whether it’s on a building site or at the drafting table, men predominate. And not just any men. Picture the average construction worker and he almost certainly is likely to be white, middle-aged and able bodied.

Whether due to structural prejudice or unconscious bias, the current reality smacks of discrimination

The homogeneity of the construction workforce is not a new revelation. Study after study has flagged the issue, especially regarding gender. Take the UK government’s latest industry survey which found a measly 13 per cent of the British building sector to be women.

Increased awareness needed to promote diversity

Where the diversity debate is changing, however, is the increased attention now being given to non-gender representation. As research highlights, construction companies are failing dismally to recruit from historically marginalised groups, especially those related to sexuality, ethnicity, age and disability.

“The inclusion of women has been on the agenda for quite some time, but levels of focus vary substantially when you look at other protected characteristics,” says Yvonne Smyth, group head of diversity and inclusion at recruitment firm Hays.

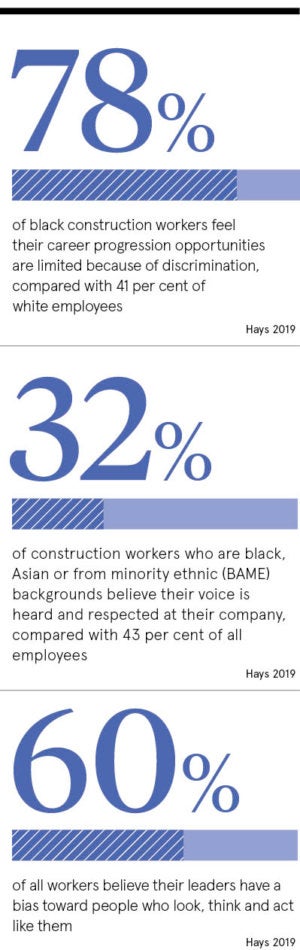

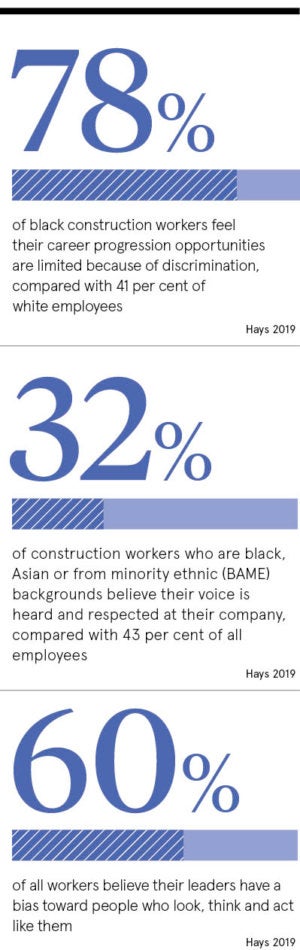

She points to a recent landmark survey conducted by Hays which, among other startling findings, revealed 78 per cent of black workers in the construction industry claim to have experienced restrictions in their career progression due to their race or other “protected” factors, such as age or sexuality.

Resolving this lack of diversity in construction represents an obvious imperative for the industry. Before anything else, there’s a question of social injustice at stake. Whether due to structural prejudice or, as the industry would argue, unconscious bias, it doesn’t much matter as the current reality smacks of discrimination.

But compelling business reasons also exist for construction companies to act and act fast. Among the most immediate is the sector’s recruitment problem. With fewer young people wanting to join the industry, contractors are struggling for manpower. In the UK, Brexit is complicating the problem further as many European workers are opting to return home.

Impending tech-led disruption also means the construction worker of tomorrow is as likely to be operating a robotically controlled bricklayer as he or, hopefully, she is to be mixing cement. Firms need to be casting their net as wide as possible to prepare themselves for future skill needs.

Role models of all experiences and backgrounds

The industry is well aware of its need to act, says Nathan Garnett, director of UK Construction Week, an annual trade show. But what exactly should firms be doing?

The industry is well aware of its need to act, says Nathan Garnett, director of UK Construction Week, an annual trade show. But what exactly should firms be doing?

For Mr Garnett, the answer has to start with fixing the sector’s image problem. Historically, construction “has never been seen as particularly welcoming”, he concedes. That needs to change. And the best way to do it, he argues, is for new or potential entrants to see positive role models higher up the career ladder.

With this in mind, UK Construction Week is spearheading a role model campaign that provides a platform for people from across the industry, including under-represented groups, to share their career stories and publicly discuss the challenges they face. The scheme has seen a four-fold increase in applications since it launched last year.

“There are some incredible people from diverse backgrounds who have managed to succeed and love their career. By projecting their stories, we can go a long way to breaking down barriers and solving the sector’s skills gap,” says Mr Garnett.

Another critical factor in advancing the cause of diversity in construction is vocal leadership from the top. At an individual firm level, the sector is awash with well-intentioned policies and specially tailored schemes. What is missing is a joint industry response.

So argues Richard Threlfall, global head of infrastructure at professional services firm KPMG. The construction industry suffers from a “lack of collective ownership” of the issue, he says, with firms looking at “what they need individually, rather than at the industry as a whole”.

To an extent, this is understandable. The construction industry is highly fragmented, with even the largest companies controlling just a tiny stake of the market. The habit of major contractors to farm out work to sub-contractors, who may sub-contract to others, also makes it difficult to pinpoint who is ultimately responsible for promoting a diverse workforce.

Inclusion as crucial as diversity in construction

Such challenges are not insuperable, according to Mr Threlfall. For inspiration, he singles out various large-scale infrastructure projects that have made inclusive recruitment a priority issue. Contractors have, in turn, adapted their practices.

He cites the Thames Tideway Tunnel, a major nine-year revamp of London’s sewer system initiated in 2015 that is run by a consortium of investors and, via its four main delivery partners, employs some 4,000 workers.

Among other steps, Tideway has sought to recruit as much as possible from local areas, widening the profile of its workforce given the ethnically diverse boroughs through which the project passes. Tideway is also certified as a disability-confident employer and as a Stonewall diversity champion, two pioneering schemes designed to improve the workplace for disabled and LGBT+ employees, respectively.

“We have focused not just on ‘diversity’ but on conscious inclusion, listening closely to how people work and what they need from the world of work, and turning that into employment practices,” says Marcia Williams, the company’s head of development and inclusivity.

The notion of listening to workers and potential employees echoes a point made by Hays’ Ms Smyth about flexible working. Construction firms can take numerous measures to make their workforce more diverse and inclusive, from tailored internships and apprenticeships to so-called returnships for older workers.

But if there is a silver bullet, Ms Smyth argues, then it is asking people what working arrangements suit them and adapting to fit. Like accommodating for religious holidays for instance, or allowing older workers time-off to care for a spouse or grandchild.

That said, no one-size-fits-all solution will fix the problem of diversity in construction. Success will depend on collective will and shared leadership across the whole industry. Only then will a fully open-to-all culture be built.

Increased awareness needed to promote diversity

Role models of all experiences and backgrounds