Yanick Kalumbu Tshiwengu, a former child miner from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), is lucky to be alive. When he was just 11 years old, Yanick went to Kolwezi to mine cobalt. Every day he descended several metres underground into makeshift tunnels and perilous shafts dug out by the miners, never knowing if he would see daylight and his family again.

How can manufacturers be sure that the cobalt which finds its way into their cars is not tainted with the blood of child miners

With no protective clothing, accidents were common. Several of his friends died underground. Yanick narrowly escaped with his life on two occasions, once when an excavator began closing the entrances to the pit shaft, blocking his escape route, and when a landslide caused a collapse. Like many of his friends, he began sniffing glue and gasoline to banish his fears, but this could not block out the painful memories that continue to haunt him.

“It was a living hell,” he says. “As children we were exploited and worked in very dangerous situations. We saw things that no child should see. There was a culture of rape and violence. Girls often fell victim to rape, which as children we were powerless to prevent. Sometimes lives were lost for a few francs. No good can ever come from the mines and I’d like to see them all closed so no child has the same experience as me.”

Demand for cobalt on the rise

Sadly, it is unlikely that Yanick, who is now 18, or the other estimated 35,000 child miners who work in western Congo’s hazardous artisanal mines, will get their wish. Why? Because the DRC, a nation the size of western Europe, mines 60 per cent of the world’s cobalt of which 20 per cent is extracted from the same unregulated small-scale mines where Yanick risked life and limb, all for less than $2 a day.

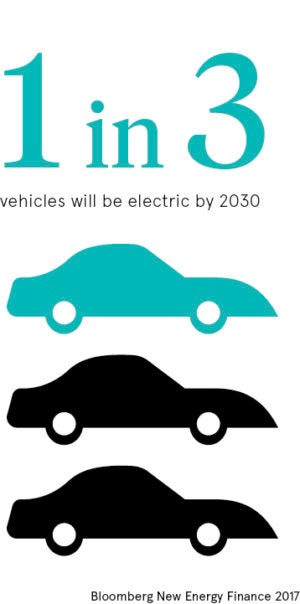

Secondly, demand for cobalt is set to increase. This rare metal already powers our mobile phones, laptops and tablets. However, cobalt is also a key component of electric car batteries. So over the next decade, with Bloomberg New Energy Finance forecasting that 33 per cent of all vehicles will be electric by 2030, automakers will need to increase their supply dramatically.

But there lies the problem. In doing so, how can manufacturers be sure that the cobalt which finds its way into their cars is not tainted with the blood of child miners? It is a question that Amnesty International, the world’s leading human rights organisation, has been asking for some time.

More oversight needed over cobalt supply chains

In 2016, after a nine-month investigation, it published a report which revealed that seven of the world’s leading electric vehicle manufacturers, including Fiat-Chrysler, BMW and General Motors, had failed to carry out due diligence over their cobalt supply chains in line with the international standards elaborated by the United Nations and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Campaigner Lauren Armistead, a lead researcher on the study, says that while there is no legal requirement for companies to report publicly on their cobalt supply chains, “unless they do this, there’s no way to be sure the cobalt in their products is abuse free”.

She explains: “It’s very simple. The OECD Guidance on Responsible Supply Chains states that business have a responsibility to carry out due diligence on their mineral supply chains. That means being able to trace their supply chains back to the smelters and refiners.

“Companies must then publish their assessment whether the smelters and refiners in their supply chain are carrying out due diligence that conforms to the OECD benchmark. Any risks or abuses found must be disclosed along with clear steps on how they can be mitigated. We found that none of the seven had published this information.”

Car manufacturers slow to respond to human rights abuses

Three years on, according to Ms Armistead, little progress has been made. In October 2018, for example, Amnesty International wrote to Daimler, Renault, Volkswagen, General Motors, Tesla, BMW and Fiat-Chrysler about potential human rights abuses in their supply chains. All responded except Tesla, but Ms Armistead says only three of the carmakers have taken welcome first steps. Renault has identified its suppliers of cobalt, while BMW and Daimler have published details of their smelters and refiners.

Three years on, according to Ms Armistead, little progress has been made. In October 2018, for example, Amnesty International wrote to Daimler, Renault, Volkswagen, General Motors, Tesla, BMW and Fiat-Chrysler about potential human rights abuses in their supply chains. All responded except Tesla, but Ms Armistead says only three of the carmakers have taken welcome first steps. Renault has identified its suppliers of cobalt, while BMW and Daimler have published details of their smelters and refiners.

But starting with the launch of its fifth-generation electric vehicles in 2020, BMW says it will take further steps to ensure due diligence. For the first time, it has pledged to buy in cobalt for new vehicle projects itself and make it available to the supply chain.

Kai Zöbelein, sustainability spokesperson for BMW, explains: “To meet our due diligence obligations, we have decided to initially source this cobalt from suppliers in Australia and Morocco for our next battery-cell generation. The mines in these countries operate in line with our sustainability standards and there are no issues with working conditions, such as child labour.”

Not enough to cease working with the Democratic Republic of Congo

But Ms Armistead says “walking away from the problem” is not the solution. “Companies cannot just impose a de facto boycott on the DRC’s cobalt, especially when they have been sourcing cobalt there. That would be a terrible blow to a country and region that relies on mining for income.

“Supply chain due diligence is not about avoiding risk altogether, but addressing it. Instead companies like BMW have a responsibility to investigate their supply chains to identify, prevent and address human rights risks and abuses in its cobalt supply chain, no matter where it is sourcing from. Failure to do so only paves the way for human rights abuses.”

Back in Kolwezi, thanks to international charity the Good Shepherd International Foundation, which is running community intervention activities in the region, Yannick was able to leave the mines. He’s now at secondary school and making up for lost time.

His experience left him with mental and physical scars, but the mines have not robbed him of hope and aspiration. “I dream that one day I’ll become a leader,” he says. “I want to change things in my country, and bring about a better future for all children and their families.”

Making supply chains more transparent

It’s a technology which its proponents say provides absolute visibility in even the most complex supply chains, not to mention guarantees immutability of records. But could blockchain really help automakers, operating in kleptocratic states like the Democratic Republic of Congo, to ensure the cobalt they receive is ethically sourced?

Volkswagen, one of seven carmakers listed in a critical Amnesty International report, is working with Minespider, a Berlin-based startup, on a pilot project to track the supply of the lead used in car batteries.

So could blockchain protocols like this one help manufacturers take conclusive steps to mitigate risks and abuses in their mineral supply chains?

Nathan Williams, Minespider’s founder and chief executive, says: “Absolutely, there is no longer any reason why minerals should be sold anonymously. With blockchain, we can finally know the entire history of our raw materials. The supply chain of the future is a transparent one.”

Demand for cobalt on the rise