FOR

In recent years the issue of pay has never been far from the headlines, whether that’s in terms of executive remuneration, gender pay reporting or revelations of just what the BBC pays its staff. Underpinning this is a belief that many people are overpaid for what they do, while others are effectively being exploited, whether deliberately or unconsciously.

Against this backdrop, more organisations are feeling under pressure to be more open about what they pay their staff and how this is worked out, whether in the form of publishing the difference between top and bottom salaries, highlighting pay bands or outlining the package that comes with each job role.

There is a strong economic case for being more transparent, says Jo Sellick, managing director of recruitment business Sellick Partnership. “One of the major benefits is that it can help to deal with inequality at many levels, the most obvious being unequal pay among those doing very similar roles and with the same amount of experience,” he says.

“In a perfect world, this type of inequality would be dealt with by employers before it ever becomes an issue, but the reality is it sometimes takes publicity and a spotlight on unfair pay before something is done to rectify the problem.”

Early evidence around gender pay reporting, which is now a requirement for large employers, suggests transparency can help to improve efficiency around salaries and bonuses, says Duncan Brown, head of human resources consultancy the Institute for Employment Studies.

Far more employers need to treat their employees like adults and genuinely demonstrate their pay and rewards are fair and justified

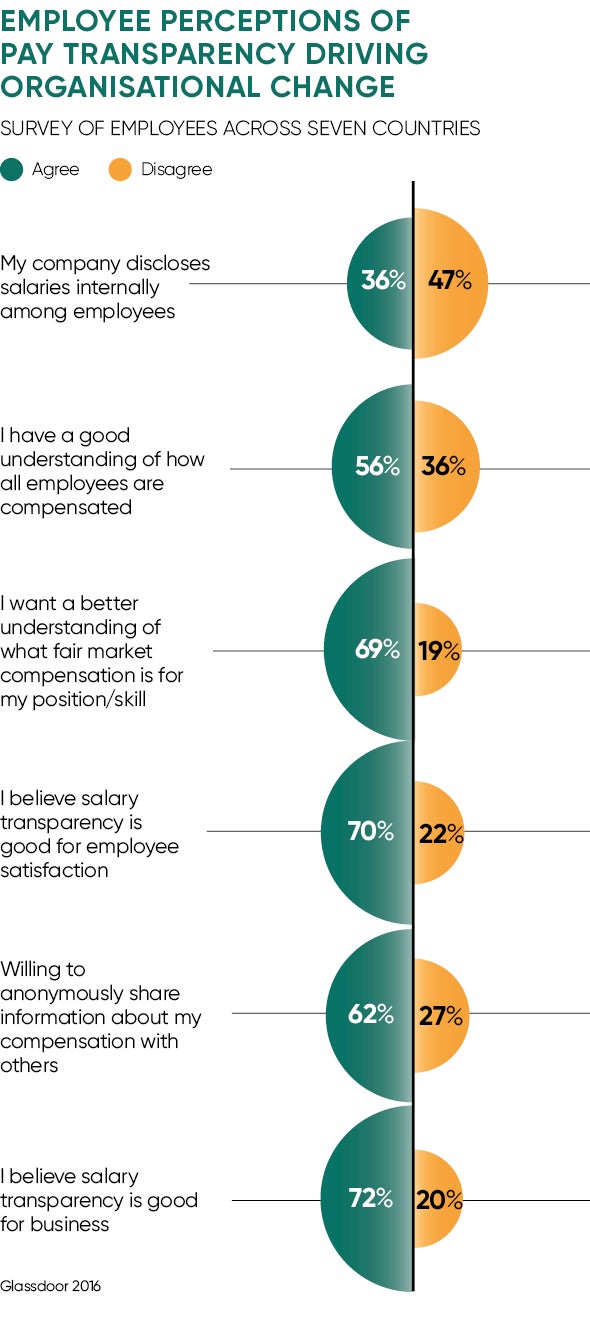

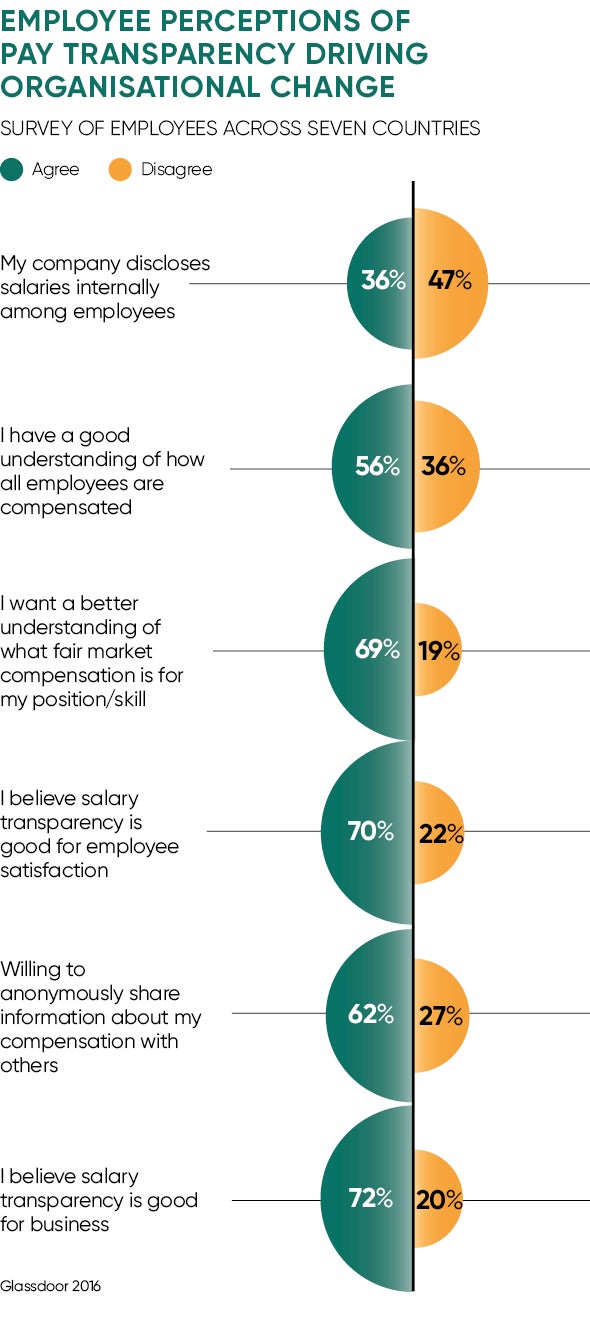

“There is clear research evidence that with employers that are more transparent about pay, perceptions of pay satisfaction and pay fairness are higher, and gender pay gaps are lower,” he says. “Far more employers need to treat their employees like adults and genuinely demonstrate their pay and rewards are fair and justified. If they do, they are likely to see more positive impacts on employee motivation from their pay spend.”

Millennials, in particular, tend to welcome a greater degree of openness around such matters, says Ruth Thomas, senior consultant at pay analysis firm Curo Compensation. “If you want to retain millennials, honesty appears to be the way to go,” she says.

“Today’s younger professionals have firmly rooted opinions on what they should know about their workplaces. Millennials have also grown up in a time where information has become available instantly. They are more inclined to share pay information with their peers to see how they stack up and determine if they are being paid fairly.”

Simply taking action to make at least some information around pay more available to employees or more widely can also help businesses to address any gaps they may have, says Alastair Woods, a partner at PwC.

“One of the things we have seen with gender pay disclosure is that organisations have thought about the consequences of the gap on their reputation, the impact on engagement of the workforce and, most importantly, have then accelerated the implementation of action plans to address inequalities. Pay transparency will shine a light on this and will mean hard questions will get asked. Where an organisation comes up short, changes will follow.”

Areas which may not be easy to justify, such as glaring discrepancies between broadly similar types of job role and opaque pension, bonuses or allowances, may also come under scrutiny as a result.

“One of the big issues we work with in organisations is the challenge of perceived unfairness in bonus distribution and specifically the individual performance ratings that drive this,” Mr Woods adds. “I suspect pay transparency will force organisations to rethink how they do this and force better ways of bonus distribution.”

AGAINST

While the idea of pay transparency may sound good in theory, some people are concerned about how it would work in practice. Steve Leeson, head of HR and talent at consultancy firm Elixirr, points out that there can often be two people who do the same job in very different ways. “The value that each person brings to an organisation might be more or less and they should be rewarded based on this value,” he says.

This was one of the issues with the recent furore over how the BBC pays its staff, Charles Cotton, senior adviser, performance and reward, at the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development, points out. “Some of it may not be justified, but other pay variations may be, because these people may do more than one job, for example if they present on the radio one day and television the next,” he says.

“That wasn’t necessarily explained. But it’s a useful discipline for organisations to think about what they are trying to reward, how and why, and if they were to publish everybody’s pay then how comfortable they would be in justifying those decisions.”

Businesses choose to compete in other ways than just salary, too. “Firms that employ individuals with entrepreneurial mindsets are more likely to focus on exponential opportunities and outcomes rather than rigid pay structures or standard benchmarks,” Mr Leeson adds. “Their employees know they will get out what they put in. It’s a culture-led approach where future earnings potential, new learning opportunities and a platform to grow individually are more important than this year’s salary.”

Not being able to see the whole picture in a headline salary comparison is also a concern for Monica Atwal, managing partner at Clarkslegal. “Transparency of pay grades and criteria for reward can only assist,” she says. “But details of individuals will also need to disclose other matrices, such as performance, expertise, critical skills, breadth of knowledge and responsibility, loyalty and length of service, so employees can understand their individual value and know the criteria to be met to move pay bands.”

Making such information freely available could disadvantage businesses by preventing them from paying salaries required to hire top talent

It’s also possible that making such information freely available could disadvantage businesses by preventing them from paying salaries required to hire top talent. “In the very volatile times we live in, where there is a constant battle between costs and talent attraction, transparency could constrain that,” says Mr Woods.

“With the digital disruption journey that companies are on, organisations need all the tools at their disposal to get hold of the right people. Organisations should get better at pay governance so they pause and consider before paying over the odds, but ultimately should not be prevented from getting the right people in.”

This is a particular concern if not all businesses engage in such openness, says Janice Haddon, founder of leadership development firm Morgan Redwood. “Making salary data public means it will ultimately be visible to competitors,” she warns. “This could give away key employment data and lead to organisations increasing salary to levels where they are pricing others out of the market.

“At all levels of employment and performance it could lead to some organisations struggling to recruit as the best talent is able to target its focus on the companies that will pay them more.” It’s also likely to create a level of tension between employees, she adds, with people feeling they are being underpaid compared to their peers.

Any organisation thinking of making such information publicly available also runs the risk of leaving themselves open to legal claims, says Michael Burd, a partner in the employment practice and chair at law firm Lewis Silkin. “Where discrepancies are identified as a result of pay rates being made public, this could well lead to an increase in complaints, grievances and even litigation around pay inequality,” he warns.

FOR