Almost dead in the water in the mid-eighties, English football refashioned itself in the 1990s. Its renaissance came with the launch of the Premier League, the result of lobbying from representatives of the main clubs at the time: Liverpool, Everton, Manchester United, Arsenal and Tottenham. The top league also benefitted from a TV deal signed with Sky in May 1992 and more indirectly from measures taken by the Thatcher government of the time.

Today, thanks to greater and more diversified popularity, a massive growth in TV money and investment in stadia, the Premier League is the third biggest money-making sports league in the world behind Baseball’s Major League and the American football’s National Football League.

The envy of Europe

Economically powerful, English football is envied by its European neighbours who see it as a model that allows clubs to achieve the virtuous reconciliation of three key aspects in which they all seek to excel: economic performance, financial performance and sports performance. However, is this really the case? When looking at Premier League clubs over a period of five years, the answer appears to be ‘no.’

To arrive at this conclusion, it was necessary to study figures issued in the clubs’ annual reports and accounts from 2010 to 2015, the period immediately before a huge leap in TV revenue changed the playing field. Financial performance was gauged through diverse indicators linked to profitability, financial autonomy, financial independence and debt.

Economic performance was measured using income from match day ticket sales, season tickets, sponsoring, merchandising, TV rights and income diversification as well as productivity of resources spent on aspects such as stadia and transfers. Finally, results in the league and the number of trophies won plus the percentage of matches won were used to analyse sports performance.

Financial performance fail

The results show that while there is a strong link between the top clubs’ economic and sports rankings, only one, Arsenal, figured amongst the top five teams each year for the three types of performance. The same five teams (Arsenal, Chelsea, Liverpool, Manchester United and Tottenham) were each year ranked as the best in terms of economic performance, but with the exception of Arsenal this did not result in their systematic presence in the top five of the best clubs for financial performance.

In contrast, six clubs (Newcastle, Norwich, Southampton, Swansea, Tottenham and West Bromwich Albion) which were not part of this ‘big five’ in terms of financial performance obtained excellent financial results during at least one of the seasons concerned.

A club with high revenue from its trade activities does not see its financial performance improve

What the research therefore shows is that there is no link between economic performance and financial performance. A club with high revenue from its trade activities does not see its financial performance improve. In the same way, a better financial performance does not ensure better economic performance.

In the same way, no link exists between financial performance and sports performance. This explains why clubs who either finished mid-table or had problems staying in the Premier League could achieve very good financial results.

Finally, there is a direct relationship between economic performance and sports performance in both directions. Good sporting results meant an increase in turnover, while clubs who achieved a rise in turnover were better placed in the league and performed decently in the cups.

Rise in revenues

The research therefore tends to show that Premier league clubs cannot follow the economic model used to guide ‘classic’ companies. This would consist of believing that sporting success allows higher revenues which allow a club to improve its financial profile and so reinvest and develop.

Premier league clubs cannot follow the economic model used to guide ‘classic’ companies

Despite an overall rise in revenue of 55% between 2010 and 2015 and an average growth from operating results of 150%, the financial situation of Premier League clubs did not improve significantly. Average levels of debt did not fall despite the strong commercial figures: a progression of 7.5% in five years. From 2010 to 2015, many clubs had negative equity which translates as virtual bankruptcy.

So, where did the money go?’ The answer: on buying players in a market where such costs soar at a scarcely imaginable rate. Between 2010 and 2015, the intangible assets of all the clubs for whom the values of players are recorded almost doubled. The Premier League, whose goal was to provide an eco-system that would ensure clubs’ measured development, had still not completely managed to achieve such an aim by 2015.

The Arsenal exception

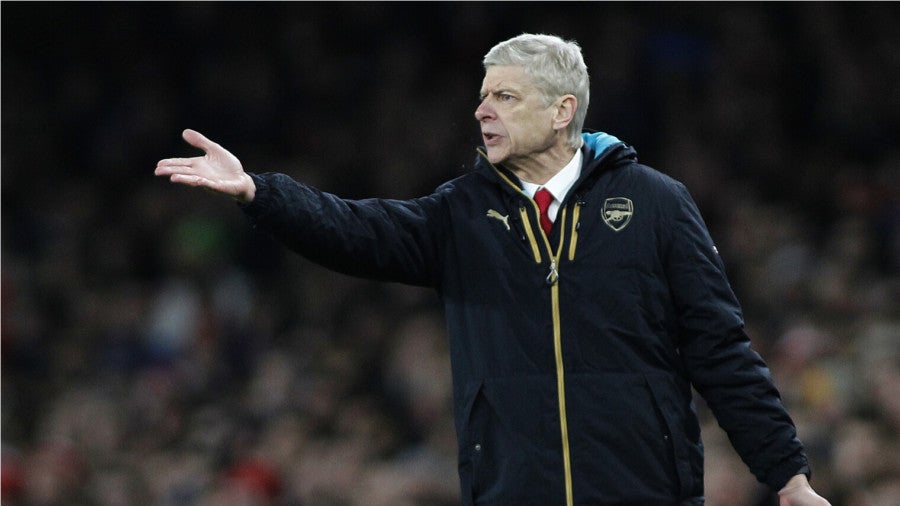

A special mention should be made of Arsenal. Each year seems to bring the same doubts about manager Arsene Wenger’s grip on the job and the perceived tight purse strings held by the chairman. Yet, no other club was present in the top five for the five seasons in question in terms of sporting, economic and financial performance. This makes Arsenal the only club able to present a coherent and viable economic model.

Arsene Wenger. Editorial credit: Mitch Gunn / Shutterstock.com

An example to follow? That would be the subject of some debate. True, the club is on an even financial keel, strong economically speaking and making above average showings on the pitch. However, the Premier League title still appears far out of the team’s reach. Maybe this is the price to pay for healthy book balancing.

Here lies perhaps the central problem faced by England’s elite group of big football clubs: how to reconcile the flair, money and passion that can sometimes seem to border on madness with the qualities of reasoning, coherence and detachment that are seen as being part of successful business. It appears that the English Premier league clubs are still some way short of finding the magic formula.

By Michael Doumpos, Emilios Galariotis, Christophe Germain and Constantin Zopounidis at the Audencia Business School, France

The envy of Europe