The word “smart” seemingly gets attached to almost anything nowadays, from the ubiquitous mobile phone to even condoms. The phrase “smart city” though turns 25 this year, coined back in 1992, around the time of the Rio Earth Summit. Typing it into a search engine today will generate more than 15 million hits.

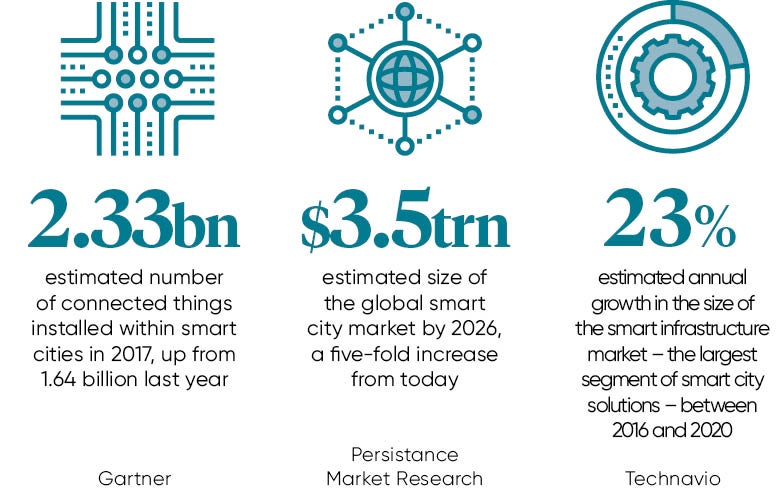

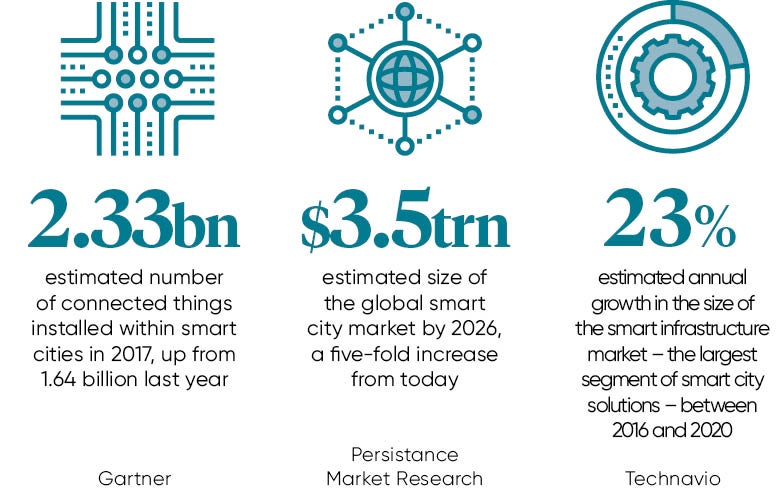

Figures for the smart city market appear similarly impressive, at first. Persistence Market Research forecasts global growth will balloon from $622 billion current valuation to $3.48 trillion by 2026, multiplying fivefold in a decade.

It’s not just about tech

Reality, though, lags somewhat behind the concept. Only with Smart City 2.0 are we recognising the need for a shift in priorities, says Professor Simon Joss, co-director of the International Eco-Cities Initiative at the University of Westminster.

“The first wave of smart cities was arguably too fixated on technological solutions. The focus was on trying to find uses for technology, rather than asking how smart technology can improve urban policy and planning,” says Professor Joss.

Misdirected early efforts were like “a hammer looking for a nail”, according to urban transformation and digitisation evangelist, board member at Future Cities Catapult, Charbel Aoun.

“We sold the technology which was the mistake. We should have sold the outcomes and social, economic and environmental impact that transforms our lives,” he says.

“I would not say we altogether ‘got it wrong’, though. Money spent and effort invested resulted in opening a market, educating the next waves and refining debate.”

While more cynical about initial motivations, Stephen Hilton, director of Bristol Futures Global, also sees evolution in evidence. “To begin with, smart cities were a marketing ploy by corporates to sell bundles of software,” he says. “But pretty soon they recognised cities didn’t just want to ‘buy smart’, they wanted to ‘be smart’. This means investing more time in understanding what each city wants and needs from technology and data.”

Every city is different

The fact every city is unique represents a massive challenge. It says something, therefore, when a global mass-market car manufacturer is inspired to pioneer custom smart mobility solutions on a city-by-city basis.

Partnering first with San Francisco, Ford Motor Company has not only acquired crowdsourced shuttle service Chariot, but also started collaborating with Motivate, to create a new Ford GoBike cycle-share service.

Speaking at the City of Tomorrow symposium, which Ford hosted alongside the 2017 Detroit Auto Show, executive chairman Bill Ford Jr explained just how much of a departure this is from their business model: “Solutions we are seeking are not regional, they are global. The tricky part, though, is that every city is different. One size will not fit all and that is why we at Ford have to be really good listeners. We have to understand cities’ issues before we try to implement solutions – and that is something different for us.”

Innovators should seek to redress, rather than further entrench, the urban divide

Incentivising radical rethinking of roles and responsibilities is part of the sustainable sales proposition for smart cities, says Rick Robinson, director of technology at Amey. He says: “As we move forward, we should be considering what are the business models, policy tools and investment vehicles that will encourage and enable individuals, businesses, communities and public institutions to innovate in ways that are financially successful, and create healthy, vibrant city communities?”

The power of smart technology can also help address climate risk and resilience, adds Mr Hilton.

Sustainability

“Through programmes like the Array of Things, Chicago, Bristol and other leading cities will ‘instrument’ their localities with low-cost, high-precision sensors. Data collected will allow researchers and policymakers to understand and model the city environment like never before, predicting and managing impacts of unstoppable climate change,” he says.

Historically, while the smart city has been integrating digital and data solutions into most physical infrastructure sectors, such as transport, energy and water utilities, plus telecoms, there has remained one glaring exception – green infrastructure.

Key to connecting the digital and the green will be data, argues Dusty Gedge, president of the European Federation of Green Roof and Wall Associations and director of the Green Infrastructure Consultancy. “Most professionals involved in smart cities are engineers. Cables and plumbing make sense to them; soil and plants, not so much,” he says.

“But smart is data, not cables or plants. So we need to be producing real-time performance data for green infrastructure to ensure it becomes meaningful to engineers, with its impact quantifiable. If we could smart-meter green infrastructure, benefits would be wired into the city grid.”

Mr Gedge is working on a project funded by Future Cities Catapult to start this process, aimed initially at planners, but intended for all professions in the urban realm.

Alongside environmental sustainability sits social sustainability. However, faced with digital discrimination, ensuring a smart city is fair and diverse, offering equality of opportunity, is tough, concedes Professor Joss. “This is perhaps the most challenging aspect of the smart city: how to harness digital technology and big data to benefit and enfranchise those at the margins of the economy and society,” he says. “Innovators should seek to redress, rather than further entrench, the urban divide.”

In all this, the speed at which technology is advancing begs the question, how do we futureproof our smart city strategies? The short answer is we cannot. As Mr Hilton says: “Smart cities are in a permanent state of beta.”

What we can aspire towards, though, is cultivation of a people-centred learning culture, enabling digital cities to be intelligent and responsive, becoming truly smart. Dr Robinson concludes: “No one can predict accurately what the impact of technology will be in five, ten or twenty years, but the one thing that’s certain is it will transform every aspect of our society, cities and economy. The only way to respond to this challenge is to become adaptable and resilient. That means preparing our cities, communities, businesses, and especially our children, to embrace constant change and lifelong learning.”

It's not just about tech