Endless words have been written on the cruelties of bureaucracy. Famous examples include the impossible situation of Josef K in Franz Kafka’s The Trial or the omnipotent claustrophobia inflicted by society in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil. But few could have imagined that bureaucracy in the real world would become quite so silly.

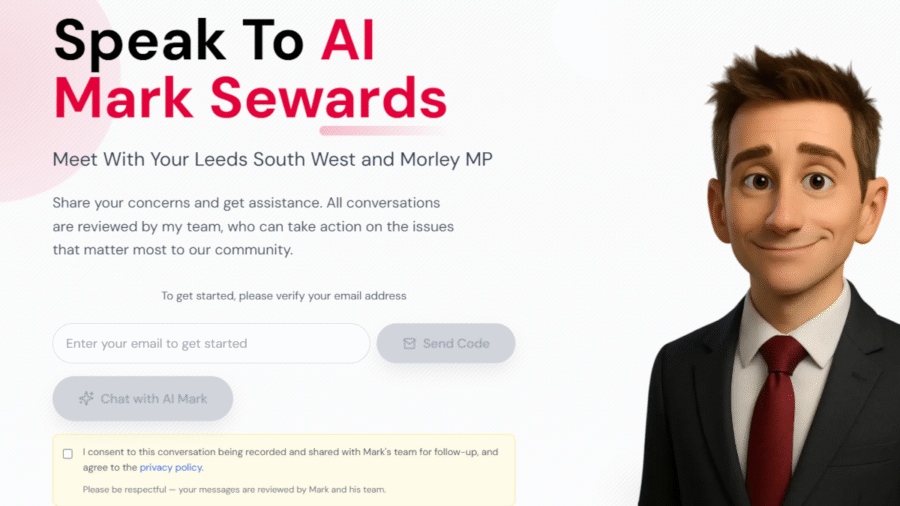

Enter Labour’s Mark Sewards, the member of parliament for Leeds South West and Morley, who has created an AI avatar of himself to interact with his constituents. This is the UK’s very first AI representation of an MP. Rather than attend a surgery with Sewards, citizens can open a website designed by local startup Neural Voice and use their computer’s microphone to put a question to a digital rendering of the representative, which looks like a concept sketch from a rightly abandoned Dreamworks project about Deloitte.

Although the avatar responds in an approximation of Sewards’ voice, it is able to give only limited answers to constituents’ queries. If it struggles to provide a response, the avatar advises users to contact the MP directly.

One might argue that Sewards’ AI stunt is meant to encourage civic participation. Such an interpretation is generous. Given its predisposition for fibbing, the chatbot could instead alienate constituents and further erode trust in the democratic process. Case in point: when a reporter at Metro questioned the politician’s support for cutting Universal Credit, the avatar claimed that Sewards opposed the manoeuvre, even though he actually voted in favour of it.

Constituents responded negatively to Sewards’ efforts, with some labelling him a “twit”. Experts told the BBC that citizens approaching the MP with serious problems might be upset by the use of such an incapable and impersonal artificial stand-in. “People may be talking about emotionally wrought problems,” said Victoria Honeyman, a lecturer on British politics at the University of Leeds. “Chatbots are developed by humans, so, like us, they can make mistakes. That could end up undermining people’s confidence in their MP.”

Similar stunts have been staged in the corporate world. Strangely, it is senior leaders who seem most keen to automate their roles out of existence. Klarna’s CEO, Sebastian Siemiatkowski, sent an AI doppelganger to a recent financial update. Sam Liang, the Otter.ai chief executive, created a “Sam-bot”, which he hopes will one day attend meetings in his stead. And Zoom’s CEO, Eric Yuan, appointed an AI avatar to deliver opening comments at a recent earnings webinar.

Although some misguided souls are forming parasocial relationships or even falling in love with AI chatbots, most of us don’t like them much – especially when they’re placed in customer-service roles, which are often better suited for the human touch.

A majority of consumers don’t want AI in customer service at all, according to a report by Gartner. They’re rarely useful and, rather than helping us solve problems more quickly, are too often just another bureaucratic hurdle to clear. Accordingly, Gartner research found that half of customer-service organisations are abandoning plans to replace support workers with AI.

In response to growing suspicion of AI in the workplace, some GenAI platforms have adjusted their messaging. They are beginning to understand that their vision of AI-powered everything is quite unsettling and that most people prefer a “human in the loop”. Many of us disapprove of LLMs stealing and digesting the work of human creatives to excrete off-kilter, derivative machine slop.

Similarly, the way to regain trust in government, which has reached a record low in the UK, surely is not to make MPs more robotic.

Only one in 10 respondents to a recent YouGov survey would prefer to use an AI chatbot over existing methods for contacting their political representative. A separate YouGov survey found that, despite all the hype about AI’s creative potential, Brits don’t think it’s very good at distinctly human endeavours such as poetry, creative writing or relationship advice.

Instead, people believe that AI real potential is in the stuff machines are best at: gathering information, providing summaries or calculating complicated sums. AI systems, say most humans, are decidedly not useful for much of anything involving interpersonal dynamics or creative flair.

Perhaps the greatest indictment of the current political environment is that Sewards believed this move would land well with the public.

Endless words have been written on the cruelties of bureaucracy. Famous examples include the impossible situation of Josef K in Franz Kafka's The Trial or the omnipotent claustrophobia inflicted by society in Terry Gilliam’s Brazil. But few could have imagined that bureaucracy in the real world would become quite so silly.

Enter Labour’s Mark Sewards, the member of parliament for Leeds South West and Morley, who has created an AI avatar of himself to interact with his constituents. This is the UK’s very first AI representation of an MP. Rather than attend a surgery with Sewards, citizens can open a website designed by local startup Neural Voice and use their computer's microphone to put a question to a digital rendering of the representative, which looks like a concept sketch from a rightly abandoned Dreamworks project about Deloitte.

Although the avatar responds in an approximation of Sewards’ voice, it is able to give only limited answers to constituents' queries. If it struggles to provide a response, the avatar advises users to contact the MP directly.