Ridley Scott’s 1982 cult film Blade Runner, based on Philip K. Dick’s science-fiction classic Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, came of age five months ago: its dystopian futurescape was Los Angeles ablaze in November 2019.

While some elements accurately hit today’s world, now stricken by the coronavirus pandemic, the planet is dangerously warm and computers can be commanded by a human voice for instance, other predictions fall short. High-collar, full-length trench coats are unfashionable, flying cars have failed to take off and, most pertinently, so-called ‘general’ artificial intelligence (AI) does not exist.

Sci-fi is increasingly becoming sci-fact, admittedly, but a technology that can replicate a range of highly advanced human characteristics – the basic definition of general AI – does not walk among us, yet. Moreover, the so-called singularity, when machines achieve sentience and technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible, is some distance away, most experts say.

“Think of general AI as HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey, or Skynet in the Terminator series,” suggests Bernd Greifeneder, founder and chief technology officer of leading automated-software organisation Dynatrace. “We’re currently nowhere near that becoming a reality, with estimates ranging from it being five years to a century away. Some even believe we’ll never see general AI step out of sci-fi and into the real world.”

Arguably that conclusion is good for the longevity of the human race, though not everyone agrees. “Unless humanity takes a wrong turn, general AI is likely to arrive around 2050, perhaps sooner,” says David Wood, chair of London Futurists. “General AI, handled wisely, can enable humanity to enter a profound new era that I call ‘sustainable superabundance’, in which we can transcend many of the cruel limitations of the human condition that we have inherited from our evolutionary background.”

Gorilla warfare in the technological jungle

Wael Elrifai, global vice president of solution engineering at Hitachi Vantara, pleads for greater caution. “When we achieve general AI, it will drastically transform our economy and society in ways we can’t even predict,” he says. “We’ll be faced with what Dr Stuart Russell, a pre-eminent thinker in the field, dubs ‘the gorilla problem’. Namely, human beings will be outmoded by machines in the same way we evolved to dominate our gorilla kin.

“Finding our place in that future isn’t a decision that can be left in the hands of a few. Technologists, educators, psychologists, policymakers and testing experts must put their heads together to consider how we measure human capital, improve human performance and ensure equity in a world where machine intelligence surpasses human capabilities.”

For the moment, though, narrow AI, which is programmed by humans to focus on a niche task, will have to suffice. The hype around AI has calmed recently, in part because business leaders have realised it is neither akin to the general AI of Blade Runner or Terminator nor a silver bullet. Narrow AI, however, is potent if pointed the right way; those who work out what direction to aim at will triumph.

Besides, as Dr Iain Brown, head of data science at SAS in the UK and Ireland, posits: “The machines have already taken over, to some extent, and with little resistance.” Our smartphones, smart speakers and driverless cars all rely on AI. “Self-learning machines are embedded in services or devices used by three quarters of global consumers,” says Brown, “and algorithms choose what news we read and the entertainment we consume.”

Canny members of the C-suite are beginning to realise the true potential of narrow AI. “General AI isn’t a pipe dream, but it is irrelevant,” says leading futurist Tom Cheesewright. “Focusing on it as a business leader is like seeing the wheel for the first time and spending your time dreaming about a Tesla. Make use of the wheel.”

Targeting niche tasks with narrow AI

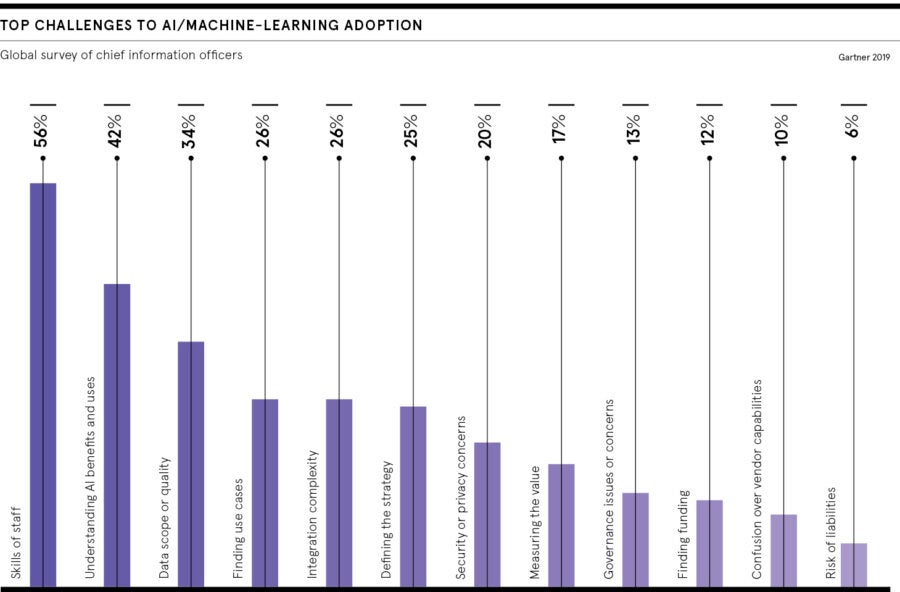

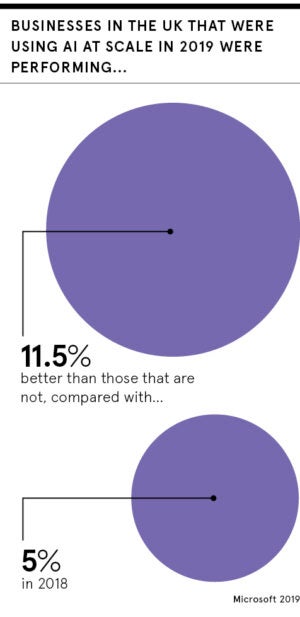

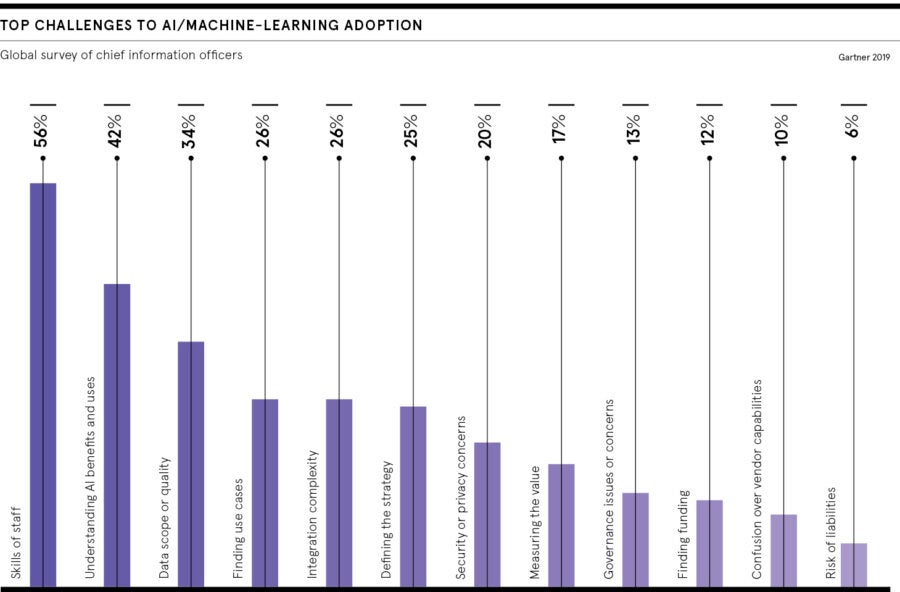

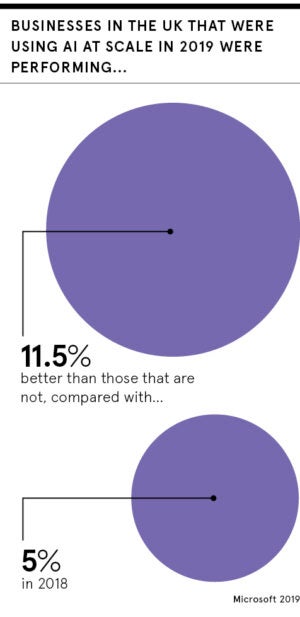

Indeed, according to Microsoft’s Accelerating Competitive Advantage with AI report, published in October, businesses in the UK already using AI at scale are performing 11.5 per cent better than those who are not, up from 5 per cent in 2018. Further, the study calculates the number of UK companies with an AI strategy has more than doubled, from 11 per cent two years ago to 24 per cent in 2019. The report also finds that more than half of organisations in the UK (56 per cent) are using AI to some extent, including a rise of 11 per cent in machine-learning from the previous year.

“Narrow AI is certainly a more rewarding prospect for businesses in the short term, as it has more specific applications and so can help to overcome the clearly defined challenges that exist today,” says Greifeneder. “It’s also easier to manage the risks and ethical implications associated with it.” As an example of granting too much autonomy to a machine, he points to Microsoft’s infamous AI chatbot Tay, which began tweeting racist and inflammatory remarks in March 2016, after just 24 hours of exposure to users on Twitter. And, like any tool, AI can be used for good or bad.

Focusing on general AI as a leader is like seeing the wheel for the first time and spending your time dreaming about a Tesla. Make use of the wheel

“We don’t need to wait for general AI to experience elements of AI utopia or dystopia,” says Peter van der Putten, assistant professor of AI at Leiden University in the Netherlands and director of decisioning solutions for cloud software company Pegasystems. “AI is used successfully to understand the structure and function of COVID-19 and to mine COVID-19 research articles. But bias has been creeping into models to determine credit card limits, decide who needs to await a court case in jail or who gets selected for preventive care programmes.”

Why general AI and man must work together

There may be justified concerns about algorithmic biases, how the associated technologies might develop and AI displacing human jobs. But it is critical for business leaders to understand what AI can achieve and it’s certainly not for every organisation.

“If you don’t understand what you are trying to solve first, you are carrying a hammer looking for a nail and AI is going to be of no real use,” says Nick Wise, chief executive of OceanMind, a not-for-profit organisation using AI to protect the world’s fisheries.

For now, the realm of sentient computers seems a long way off. And if we humans are prudent, if or perhaps when general AI becomes a reality, man and machine will augment one another. As Brown concludes: “The future belongs to the cyborg: humans working hand in glove with AI, rather than the android alone.”

Gorilla warfare in the technological jungle