Science fiction has long speculated on the danger of a dystopian future and machines powered by artificial intelligence (AI). But with the advent of big data, we no longer need to speculate: the future has arrived. By the end of March, West Midlands Police is due to finish a prototype for the National Data Analytics Solution (NDAS), an AI system designed to predict the risk of where crime will be committed and by whom. NDAS could eventually be rolled out by every police force in the UK.

Ultimately, we need to be able to choose as a society how we use these technologies and what kind of society we really want to be

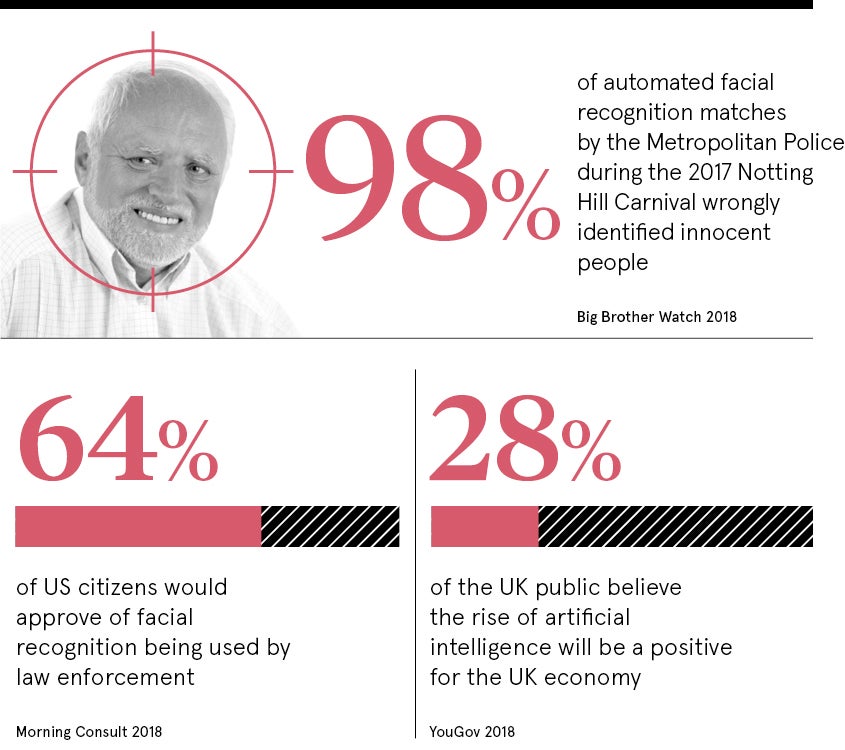

Fourteen police forces around the UK have used or planned to use such tools. But a report published in February by human rights group Liberty warns that far from being objective, police crime-mapping software reinforces pre-existing biases about who commits crime.

Current mapping tools use past crime data to identify so-called high-risk areas, leading to more intensive patrolling. Yet these areas are often already subject to disproportionate over-policing. By relying on data from police practices, according to Liberty’s advocacy director Corey Stoughton, these tools might simply “entrench discrimination against black and minority-ethnic people”.

Police mapping tools turning citizens into suspects

Ben Hayes, a data protection and ethics adviser to the European Union, United Nations and other international organisations, warns that the increased use of such mapping tools is increasingly turning ordinary citizens into suspects.

“People can be categorised as vulnerable, at risk, threatening, deserving or undeserving,” says Dr Hayes, noting that this tends to target those already marginalised. “Services such as border control, policing and social welfare are all subject to inherent bias. Machine-learning doesn’t eliminate those biases, it amplifies and reinforces them.”

Predictive-mapping tools have nevertheless become ubiquitous among national and local governments around the world. Among the most widely used is Mosaic, a geo-demographic segmentation tool that profiles every single person in the UK using 850 million pieces of data.

Created by marketing company Experian, Mosaic is used extensively by councils and political parties in the UK. It draws on GCSE results, welfare, child tax credits, the ratio of gardens to buildings in different areas and even internet scraping of public websites to build its profiles.

According to Silkie Carlo, director of privacy campaign group Big Brother Watch, Mosaic “perpetuates crude stereotypes, such as the category of ‘Asian heritage’, or ‘dependent greys’, or the use of postcodes to link people living in certain areas to alleged risks of certain behaviours”.

Smart cities magnify scope for abuse

Councils and police often combine such categories with other highly sensitive data, including children’s school records, use of social services and family issues. These can then be used to “predict” whether a person might be at greater risk of committing benefit fraud, engaging in violence or even being sexually abused.

“There are already real risks of discrimination against minorities or poor people due to mistaking correlation for causality,” says Ms Carlo. “When you add into the mix a complex AI tool, this simply covers those biased decisions with a veneer of scientific credibility.”

As cities around the world from London, to Dubai, to Shanghai aim to become “smarter” in using data technologies to improve government services, the scope for abuse is magnified.

The main problem with smart cities is that sensors are on all the time, says Ann Cavoukian, a former privacy commissioner in the Canadian province of Ontario, who now heads up the Privacy by Design Centre at Toronto’s Ryerson University. Not only is there no opportunity to consent to the use of personal data, that data can then be used in ways outside your control.

Citizens might be penalised for jaywalking or not meeting recycling targets, or have their credit rating affected due to social media usage. Meanwhile, private data companies contracted to help run smart city processes have tremendous access to people’s entire lives, blurring the checks and balances essential to democracies.

Making data anonymous to police is the only fair way

Dr Cavoukian’s solution is simple: data should be anonymised.

By scrubbing personal identifiers from the data, it can still be used to improve public services, but avoids the risk of wrongfully persecuting individuals.

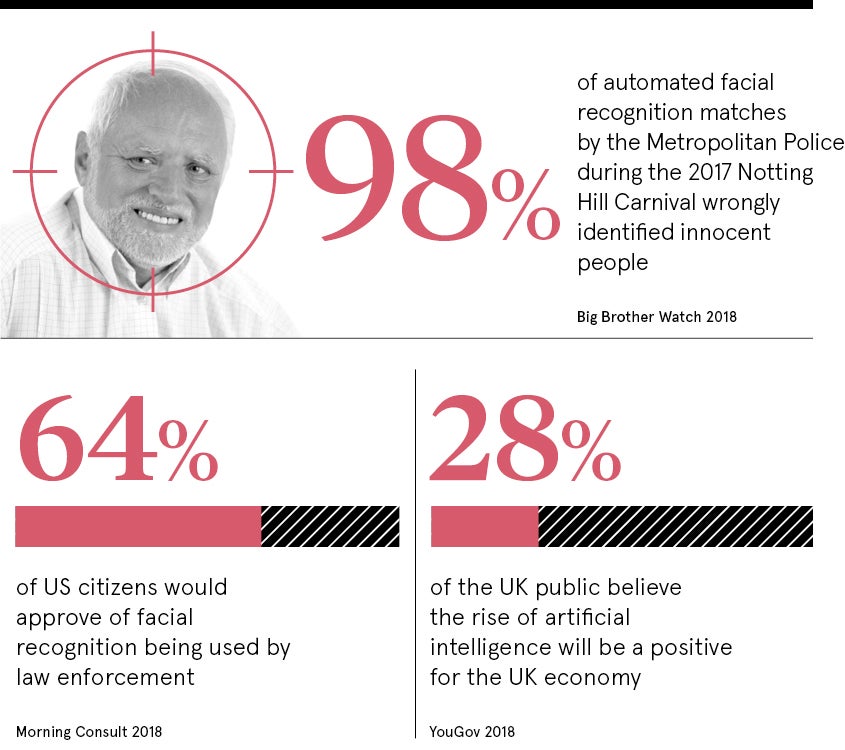

For Ms Carlo, the key is transparency. “No one wants to be a Luddite, but local authorities are running before they can walk,” she says. “The starting point before they use such technology is to consult local people in advance, which hasn’t happened. People are being assessed through these systems without their knowledge or consent.”

Lack of transparency on what technology is being used and where is compounded by a complete lack of legal oversight. According to Dr Hayes, this urgently needs to change to avoid creeping into more authoritarian societies.

“Right now there is a legal vacuum which has given carte blanche to governments and companies,” he says. “This has led to a race to the bottom in standards as we compete with countries like China. Ultimately, we need to be able to choose as a society how we use these technologies and what kind of society we really want to be. Regulation need not be viewed as a barrier to innovation. A robust legal framework can provide the oversight to make technology work for people, rather than against them.”

Police mapping tools turning citizens into suspects

Smart cities magnify scope for abuse