Employee attrition can be a difficult challenge for businesses at the best of times, but the coronavirus pandemic and the chaos it has wrought on workplaces compounds issues of staff retention.

Employee engagement has become a major issue as workplaces become remote: UK public service productivity fell by a third in the second quarter of 2020, according to the Office for National Statistics. And world-changing events like pandemics crystallise thoughts about the future. Some employees may be re-evaluating what they want as a work-life balance and coming to the conclusion they need to leave the company.

“I’ve never seen human resources more prominent in the workplace,” says Sir Cary Cooper, professor of organisational psychology and health at Manchester Business School, and president of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. In a competitive business world, where a number of employees are likely to look at changing careers, making sure you attract and retain talent is key.

Avoiding a high turnover rate of staff

Data compiled by the Health and Safety Executive pre-pandemic found 57 per cent of all long-term absences from the workplace were down to stress, anxiety and depression. That’s likely to be compounded as employees find themselves away from the collegiate atmosphere of the workplace, left to fend for themselves against tough deadlines. “How do you pick people up remotely who aren’t coping?” asks Sir Cary.

It requires building robust relationships with colleagues outside work-oriented goals to reduce the rate of employee attrition. This starts at the very beginning of the process.

What are you going to do to help people who have never worked in the company, who have only ever been online?

“Everyone needs to look at their induction processes and think about whether they need to widen them to make people feel part of the organisation,” says Professor Heather McGregor, head of Edinburgh Business School.

She recently did an entire interview process for a new position at the same time as another new colleague and it was months until they found a way of working together efficiently, when they were finally able to thrash it out together in a physical room.

“It’s difficult to build relationships over Zoom,” says McGregor. “When you arrive in a company, the induction needs addressing, and the second thing is how do people build relationships? What are you going to do to help people who have never worked in the company, who have only ever been online?”

Improving professional growth

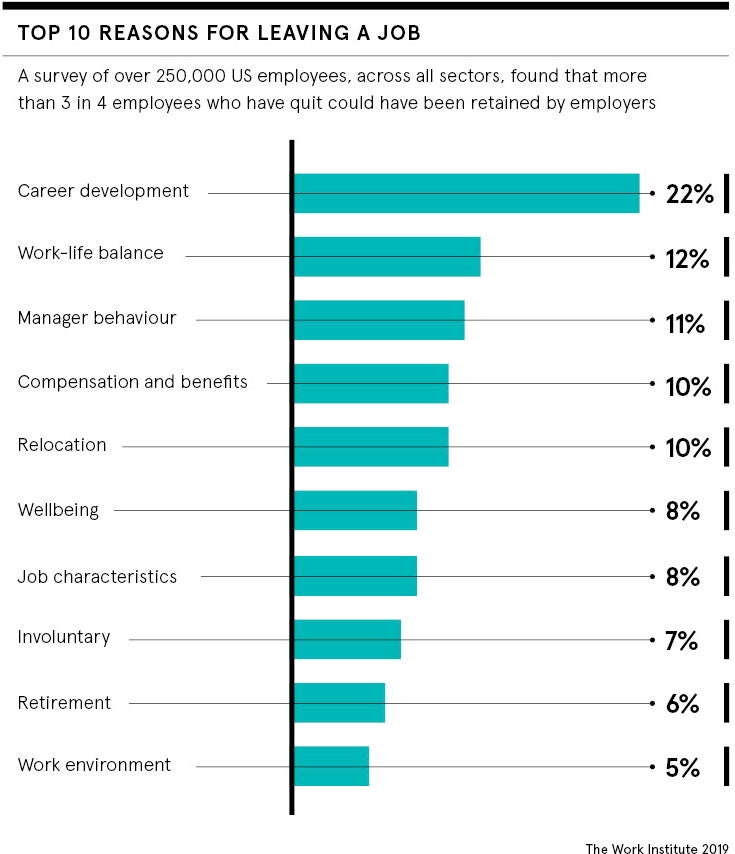

Many things have been put on pause or stalled as the pandemic bites, but one thing that can’t is the potential for workplace progression. One of the biggest contributors to employee attrition is workers feeling they’ve reached the limit of where they can go in a company. Professional growth and a sense of purpose drive employees the most to work well. Knowing there’s still the potential for promotion is key.

“We don’t have the right kind of line manager in the UK and many other countries,” says Sir Cary. “We recruit and promote people to managerial roles on the basis of their technical skills, not their people skills. Now, more than ever before, we must ensure there’s parity, when people go for managerial roles, between people skills and technical skills.”

Managers must be able to reassure workers there are opportunities for progression to keep down the number of employees who leave, and they can do this with support from HR. Providing a roadmap for where someone comes from and where they can go means they’re less likely to head for the door. Job security and assurance are key in times of crisis and providing both avoids losing vital talent at a time when onboarding new employees is more complicated than ever.

Checking in on work-life balance

It’s also more difficult to pick up signals that something is wrong when the workforce is scattered to the winds. An unhappy employee usually makes themselves known when you’re interacting with them in an office eight hours a day. When they’re communicating only via email or occasional video calls, it can be difficult to identify issues.

Checking in on people, and providing wellbeing support through initiatives that identify where problems are coming to a head, and acting quickly to try and solve them, is the solution to the revolving door of workers leaving the company for pastures new.

“We should be doing regular wellbeing audits to see how people perceive their work environment because of the rapidly changing nature of work,” says Sir Cary, who points to the example of the last significant change in our economy, the 2007-8 financial crash. Then, an HR director in the financial services sector came to him and spoke about “regrettable turnover”. “We’ve lost 35 per cent of our staff,” the HR director said. “How do we retain them?”

The answer is support and providing a sense of purpose. “Millennials, unlike previous generations, will leave if they don’t like the culture they’re in,” says Sir Cary.

But it’s not just millennials; confronted with the enormity of a world that has totally change. People are recalculating what they want from their workplace and employee attrition is rising. While the market for workers is likely to be significant, due to imminent economic turbulence, it’s far easier and cheaper to invest time in wellbeing initiatives than lose a talented worker and have to replace them with someone new.

How to nail a remote interview

No matter how hard you try, employee attrition can be unavoidable, making online recruitment inevitable. The coronavirus pandemic has thrown up an entirely new challenge: successfully identifying and onboarding employees remotely. So in the world of the Zoom interview, what should you look for?

“The critical thing about video interviews is that, as with in-person interviews, 85 per cent of communication is non-verbal,” says Professor Heather McGregor at Edinburgh Business School. “You have fewer non-verbal clues in a video interview.”

So paying close attention to those non-verbal clues when they appear is important: how is the candidate dressed? How comfortable are they communicating through a webcam, given it’s likely to be the norm for some time to come?

And what’s their background like? “The first thing you have to think about is whether they’re going to have a green screen background or not, or whether they blur it out,” says McGregor. “I think that matters because you communicate so much through what you don’t say and people make assumptions.”

Making assumptions is one of the biggest risks for businesses looking to hire people in the age of Zoom. Assumptions affect decisions and it can be easy to misconstrue a misplaced pot plant or a slightly messy background as an indication someone is unreliable when it could simply be that they’ve had to home-school their children due to a COVID-19 outbreak at nursery.

That personal touch is difficult to replicate online, too. “Your personal expression is not as easy to read when you’re in a little square, especially if you’re in a panel interview,” says McGregor. “Your bit of the screen is small; unless all the people on the panel have been told to put you on speaker view, you’re small. When you’re speaking, you don’t have the same level of expressiveness digitally as you do in person. I think it’s harder to convey things.”

So bear all this in mind and be prepared to make decisions without all the information you would normally have with an in-person interview.

Employee attrition can be a difficult challenge for businesses at the best of times, but the coronavirus pandemic and the chaos it has wrought on workplaces compounds issues of staff retention.

Employee engagement has become a major issue as workplaces become remote: UK public service productivity fell by a third in the second quarter of 2020, according to the Office for National Statistics. And world-changing events like pandemics crystallise thoughts about the future. Some employees may be re-evaluating what they want as a work-life balance and coming to the conclusion they need to leave the company.

“I’ve never seen human resources more prominent in the workplace,” says Sir Cary Cooper, professor of organisational psychology and health at Manchester Business School, and president of the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development. In a competitive business world, where a number of employees are likely to look at changing careers, making sure you attract and retain talent is key.