Water count and numeracy in pints and litres is fast becoming a core sustainability skill for responsible and resilient businesses.

“Water is firmly on the corporate agenda,” says Cate Lamb, head of water at CDP (Carbon Disclosure Project). It is a matter of risk and reward. She explains: “Many businesses are already experiencing detrimental impacts. In 2016, companies engaging with CDP reported a total of $14 billion in costs from water-related events, such as stranded assets due to loss of licence to operate.

“On the flip side, 66 per cent see opportunities in water from cost-savings to brand value and shareholder confidence.”

Economic drivers are strong in themselves, but only if you factor in energy spend, argues managing director of business services at the Carbon Trust, Hugh Jones. “The biggest financial motivation to address water consumption is concern around energy costs and carbon emissions,” he says. “In most regions, water is comparatively cheap, even where not necessarily abundant. The big costs come from energy needed for heating, cooling, pumping or treating water.”

The connection between water and energy is actually getting deeper, says Craig Simmons, chief technology and metrics officer at global sustainability consultancy Anthesis Group. “As water supplies dry up and sources become more polluted, there is a drift towards more energy-intensive technologies to address the shortfall,” he says. “The link between carbon and water is getting stronger – the cost of water evermore closely aligned with the cost of energy.”

Unlike energy and carbon, however, water is a very site-specific commodity as you can work smart with what you have, but cannot easily generate more supply onsite or offset excessive impacts elsewhere. The secret to water in three words appears to be “location, location, location”.

Where you do what you do often mandates water efficiency for some firms, says Benedict Orchard, environmental sustainability manager at Adnams, one of the only UK breweries to complete full life-cycle assessments for water and carbon. “It’s a simple case of business resilience. In one of the driest parts of the country and restricted on how much we can use, we believe water is currently undervalued financially,” he says.

At just 2.8 pints of water for every pint of beer, Adnams has one of the lowest water ratios for a UK cask brewery. For Mr Orchard, benefits of footprinting are obvious: “It will immediately highlight potential efficiencies and water-saving opportunities, for example reusing wort [unfermented beer] cooler water as hot brewing liquor.”

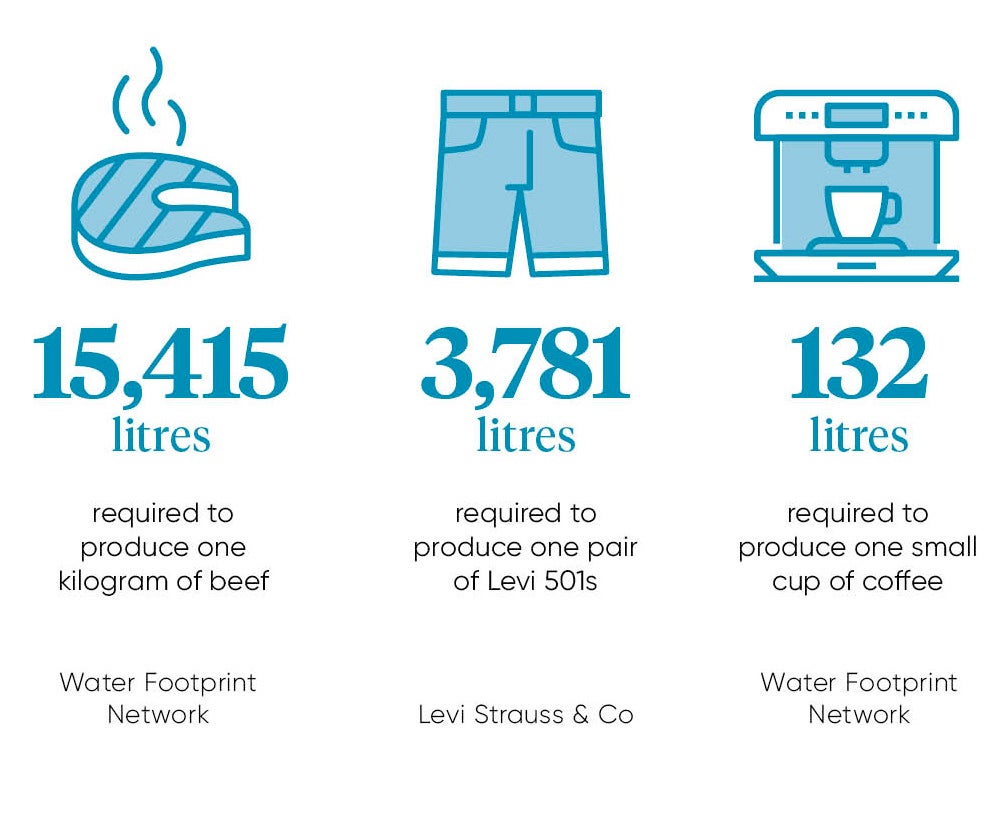

Given water quality and availability are so location specific, footprinting helps identify priorities, agrees Michael Kobori, vice president, sustainability, at Levi Strauss & Co. “According to product life-cycle assessment, there are 3,781 litres of water embedded in one pair of Levi 501s. Two thirds is used in growing cotton and nearly a quarter by consumers,” he says.

Focusing time and resources on cotton and consumers, which make up 91 per cent of water use, the company has made great progress innovating in denim manufacturing with its Waterless Collection, as well as implementing the apparel industry’s first water recycle/reuse standard.

Collaboration has been key. “It is crucial when the stage in the life cycle is several steps removed from our direct influence, as with cotton cultivation, or water quality and availability are impacted by other commercial, agricultural or governmental actors, which is practically everywhere,” says Mr Kobori. “For these reasons, we work with the Better Cotton Initiative, WWF, NRDC, CEO Water Mandate and Project Wet Foundation to address shared water issues and raise awareness.”

Water stewardship is also a major priority at Ford Motor Company. Not content with 72 per cent water reduction per vehicle since 2000, the automaker aims to reduce usage by an additional 30 per cent by 2020, with a long-term goal of zero drinking water in manufacturing.

Ford has also been busy collaborating with the United Nations, Business Alliance for Water and Climate, CDP, World Business Council for Sustainable Development, SUEZ, Nalco and others.

This outreach brings more awareness to efforts involving a variety of stakeholders, says Ford’s John Cangany. “Transparency is critical to continued progress with water stewardship, as well as with broader corporate social responsibility efforts,” he says. “Working with leading NGOs and water experts has greatly aided the company’s public goal-setting.”

In addition to companies and brands showing leadership on water, sectors too are in the vanguard, says Mr Simmons. “There is no doubt agriculture, as the biggest consumer globally, is leading on water management,” he says. “And given the huge water footprint of many foods we eat – it is quite common for the mass of water needed to bring the product to market to exceed the finished weight by a factor of several hundred – efficiencies can pay huge dividends.”

If climate change is the wolf, water is its teeth

Amanda Curtis, senior environment manager for Plan A foods at Marks & Spencer, is acutely aware of the issues. “At M&S, water is critical to our business,” she says. “We’ve often said that if climate change is the wolf, water is its teeth.”

For M&S, better understanding of usage is key, with more than 90 per cent in the supply chain. Ms Curtis adds: “Quick wins are often through water-efficiency measures at farm level, such as drip irrigation, rainwater harvesting, removal of alien water-thirsty plant species and smart agriculture.”

Sustainability scorecards encourage suppliers to embed water stewardship and cut usage. Despite this laser focus, though, progress can still prove slow and solutions complex.

Ms Curtis concludes: “Moving from efficiency to stewardship requires farmers to go beyond their farm gate, and work with different organisations and neighbouring businesses to address the wider issue.

“Often, positive outcomes can only be seen over the longer term, across a wide area and link to social and biodiversity elements requiring investment into resource for many years.”