Keeping meat and juice fresh can be an expensive business for supermarkets. The energy used by chilled aisles can account for 40 to 60 per cent of a store’s total energy bill, according to the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

With the retail industry looking to reduce its carbon footprint, some supermarkets, including Aldi and Lidl, are turning to renewable energy technologies, such as solar panels, anaerobic digestion and wind turbines, to provide power to stores and distribution centres.

The problem is, while these energy sources are clean, they’re subject to interruptions. Solar panels require the sun to shine, but supermarkets need to keep refrigeration units running throughout the night.

“Replacing conventional power generation with renewable generation is essentially moving from a reliable, centralised infrastructure to a decentralised and intermittent energy supply,” says Stefan Schauss, president of CellCube Energy Storage Systems, which is headquartered in Toronto. The company is aiming to become North America’s leading producer of vanadium electrolytes for the energy storage industry.

“Energy storage promises to solve all the quality and stability of supply issues for uninterrupted production in the wholesale and retail chain,” Mr Schauss adds.

Lithium ion batteries leading charge for energy storage

Leading the charge when it comes to energy storage are lithium-ion batteries: literally the same as the battery packs found in electric cars and smartphones, just on a bigger scale. According to GTM Research, lithium-ion battery storage could increase 55 per cent every year until 2022. The United States is expected to see the most deployments, followed by China and Japan.

In December 2017, Tesla switched on the world’s largest lithium-ion battery in southern Australia, which stores excess energy generated from a nearby wind farm to meet demand during peak periods. Within its first month, the battery reportedly kicked in 0.14 seconds after one of the country’s main power stations experienced an unexpected outage.

Despite lithium-ion battery storage being able to respond more quickly than traditional backups and solve the immediate problems regarding stability, it has downsides.

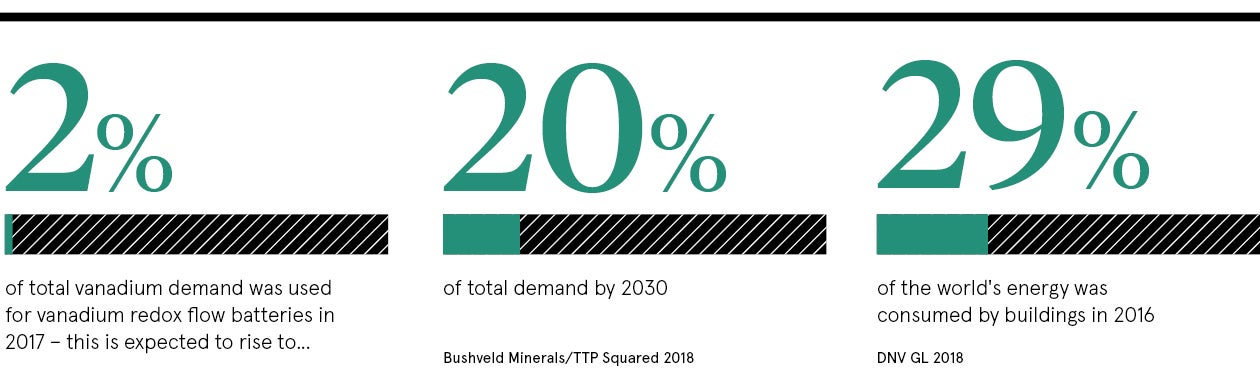

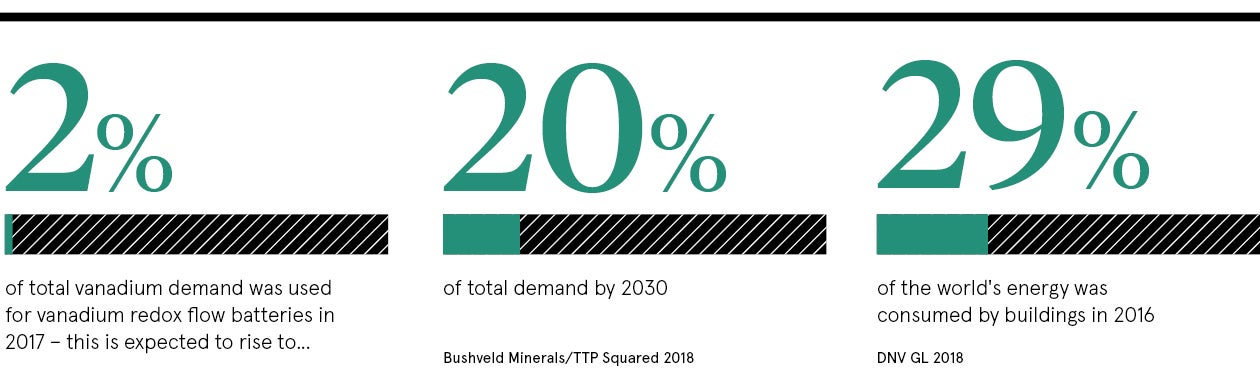

Lithium-ion batteries are ideal for filling in the gaps, but not for long periods of intermittency. Their life cycle, on average, is between two to seven years. In comparison, vanadium redox flow batteries, which CellCube specialises in, can store more energy and last up to 25 years. This makes them suitable for businesses that want to store up enough energy to support them for weeks or months when the sun isn’t out or the wind isn’t blowing.

Vanadium redox flow could be next big thing for energy storage

“Vanadium redox flow batteries connected to the grid are increasingly being recognised as the future of energy storage,” claims Mr Schauss.

The leading developer of vanadium flow technology in the UK is redT. The company has a number of operational installations, including in Cornwall on a 600-acre farm and 28-cottage holiday retreat, and in Melbourne, where a vanadium flow-lithium battery hybrid system has been installed at Monash University.

According to Scott McGregor, chief executive of the London Stock Exchange-listed company, its redox flow devices – he prefers to call them machines rather than batteries – can cut large businesses’ energy bills by half.

“These machines can cycle heavily every day for many years without degrading. They aren’t small and sexy, but that’s not their purpose; they are true storage infrastructure, designed for heavy industrial use unlike disposable lithium batteries,” says Mr McGregor.

Businesses not investing in energy storage may suffer

Another financial benefit of redT’s machines is users are able to make money by supporting the grid at peak times, giving them “a long-term hedge against rising energy prices”, adds Mr McGregor. This is “energy storage 2.0”, he says.

The price businesses will pay for not investing in energy storage or battery storage could be high. At the same time, businesses that are mission critical, such as datacentres, are risk averse and will already have uninterruptible power supply (UPS) systems in place, says Stephanie Jamison, a managing director at Accenture, who leads its transmission and distribution division.

For this reason, such businesses are likely to play it safe and the way they operate, relying on diesel or gas-powered backups, for example, is unlikely to change in the short term.

“Businesses without mission-critical processes, but still suffering significant impacts from outages or from poor quality, have generally been unable to justify the cost of deployment,” says Ms Jamison. “Now they have the opportunity to use innovative storage technologies to improve power reliability and provide new revenue streams.”

Lithium ion batteries leading charge for energy storage

Vanadium redox flow could be next big thing for energy storage